Having previously worked as an assistant to Pep Guardiola at Manchester City, Enzo Maresca is often considered a Guardiola disciple — like Mikel Arteta, his opposite number in Chelsea’s 1-1 draw with Arsenal at Stamford Bridge on Sunday afternoon.

But Maresca has often pointed instead to Guardiola’s predecessor at City as his true coaching inspiration. Maresca played under Manuel Pellegrini at Malaga towards the end of his career, then served in his coaching staff at West Ham United.

“Manuel is, for me, like a father,” Maresca told Manchester City’s official website in 2020. “Manuel was both the coach and the person who convinced me to try to be a coach myself when I finished playing, he said to me: ‘You have to try to become a coach because I think you think you can become a good coach’.

“If ever I had some doubt, he always helped me — both as a player and in the last two years as a coach at West Ham. I have a tremendous relationship with him..… as a coach, for the way he worked with players and managed situations it was, for me, one of the best experiences.”

Tactically, one of the curious features of Pellegrini’s approach — particularly in his spells at Villarreal, Manchester City and West Ham — was his insistence on his back four holding an offside line on the edge of the penalty box, rather than dropping back inside it. At times, it catches the opponents offside. But on other occasions, it means the defensive line ends up in the wrong position — too high up, and too easy to beat. That cost Chelsea a goal against Arsenal on Saturday and has been an issue throughout Maresca’s first three months in charge.

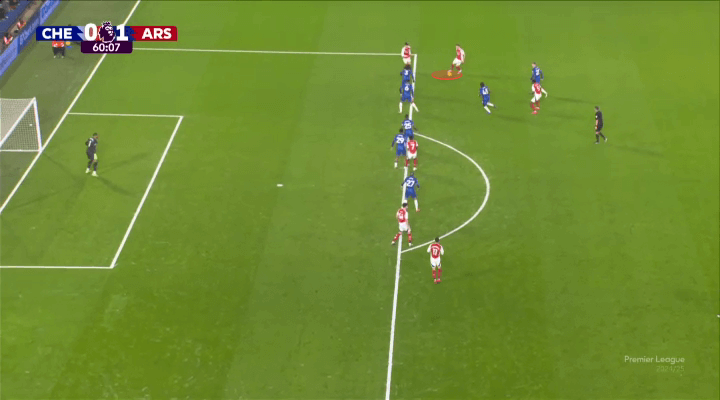

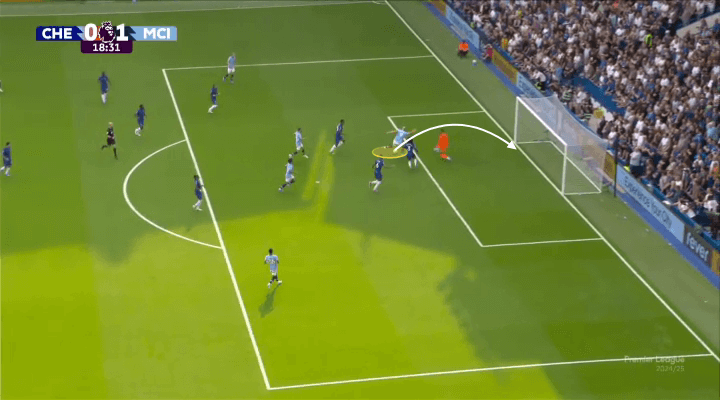

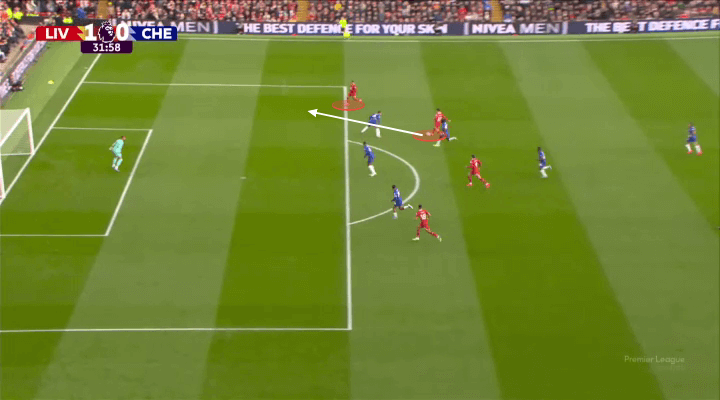

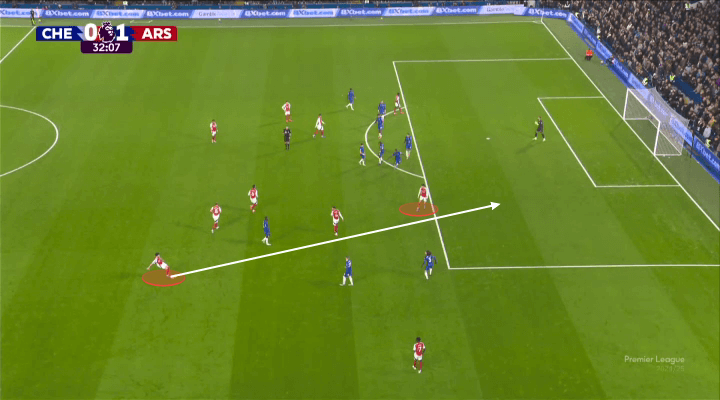

Here’s the goal on Saturday, scored by Gabriel Martinelli. Arsenal’s chief playmaker Martin Odegaard, perhaps the Premier League’s best through-ball player, is in possession 20 yards out in his favoured inside-right position. Chelsea’s defence, as usual, are holding their defensive line on the edge of the box.

In basic terms, you can’t fault their organisation — five players are pretty much in a line. But they’re very obviously too high up in this situation. There’s just too much space in behind when the player in possession is in that position.

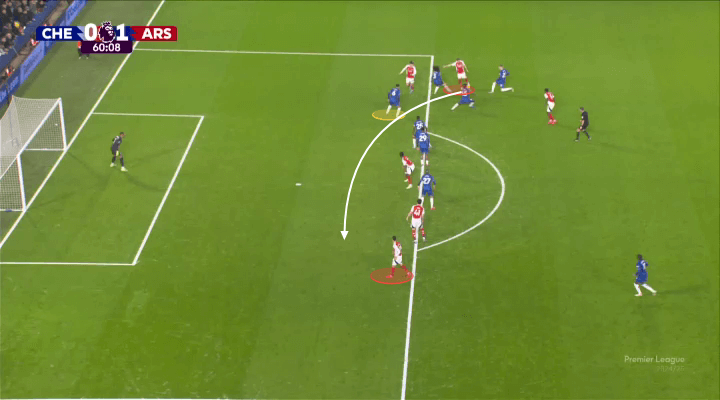

Odegaard has a relatively easy task of chipping the ball in behind for Martinelli, who is unmarked and has oceans of space to bring the ball down and fire home. He was played onside by Levi Colwill. Yes, Colwill is deeper than the rest of his team-mates, and at fault for not playing on the edge of the box as Maresca wants. But Colwill is surely closer to the ‘correct’ position in this situation than anyone else. If Chelsea had been 3 yards deeper, the pass would have been harder.

A similar thing happened for Curtis Jones’ winner against Chelsea last month.

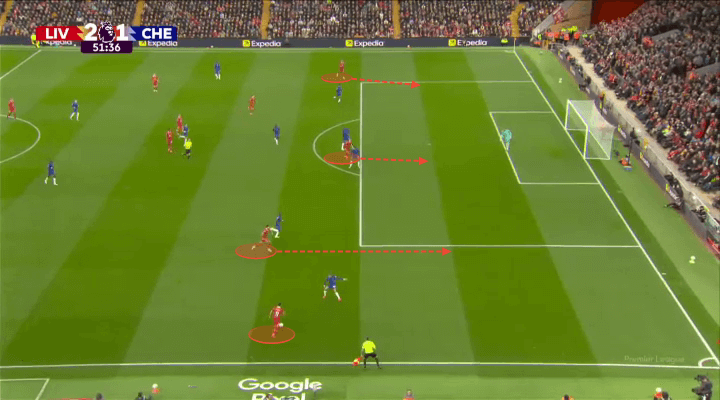

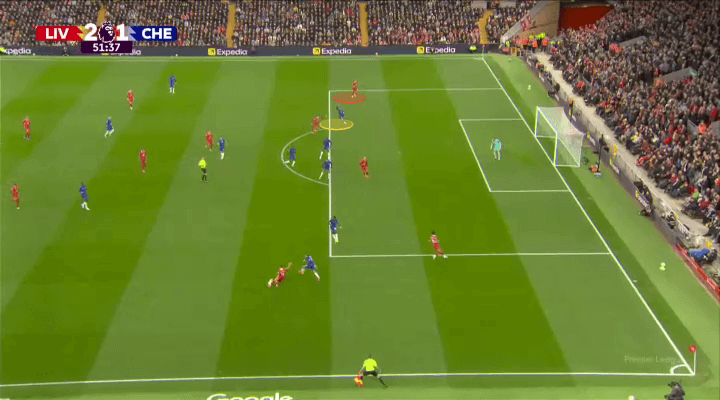

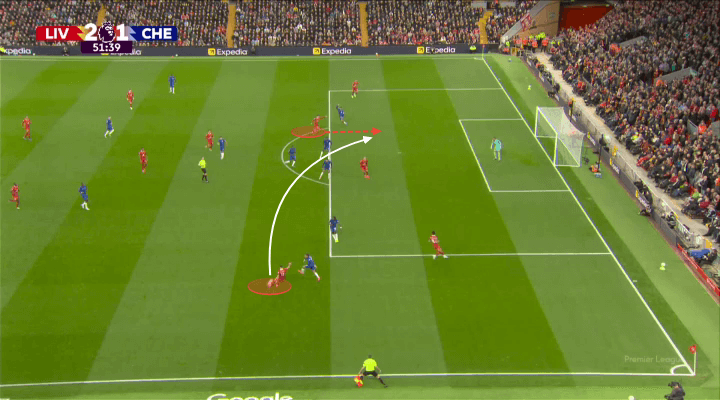

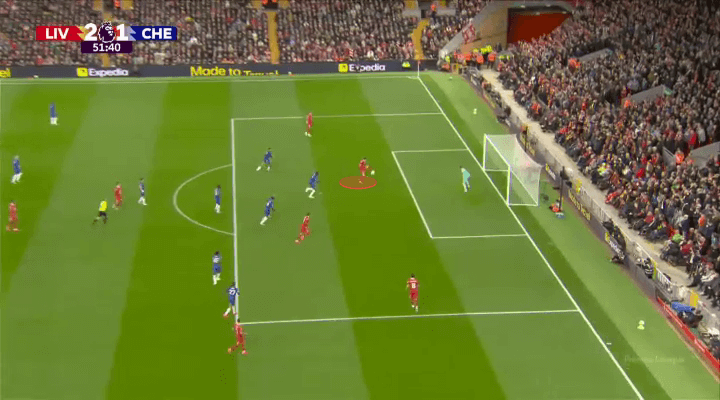

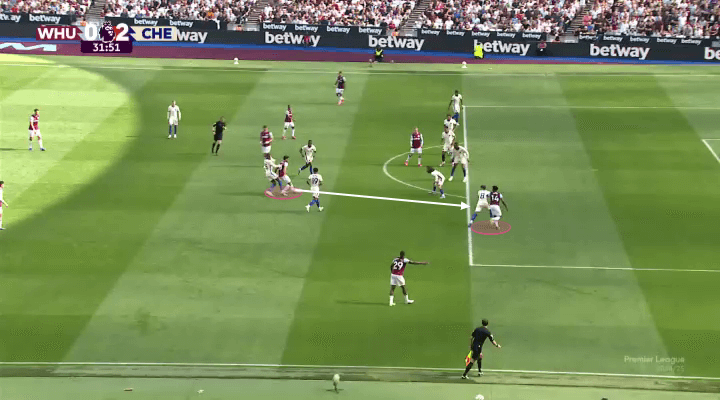

Here’s Mohamed Salah on the ball in roughly the same position as Odegaard, albeit closer to the touchline. Liverpool have three runners set to go in behind: Dominik Szoboszlai on the near side, Cody Gakpo on the far side, and Darwin Nunez through the middle.

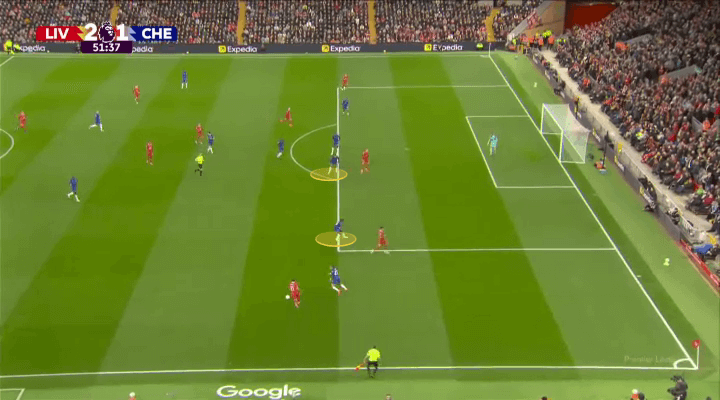

As Salah moves inside, Romeo Lavia — tracking Szbobszlai’s run into the near-side channel — stops dead as soon as he reaches the edge of the box. Colwill, the closest centre-back, does the same. Szoboszlai and Nunez have both run offside.

The problem is on the far side, where Reece James — playing his first game under Maresca and therefore not accustomed to the offside tactic — has dropped two yards deeper than his team-mates. Again, while James is at fault for not following the plan, his position is more correct compared to his team-mates, positioned 18 yards from goal. when the ball is 22 yards from goal. James appeals for offside, presumably looking across at Nunez and Szoboszlai. Gakpo behind him is offside, too.

But Chelsea hadn’t banked on the run of Curtis Jones, who knows precisely where Chelsea’s back line will be positioned, and times his run perfectly to run in behind and finish.

This issue has continually caused problems.

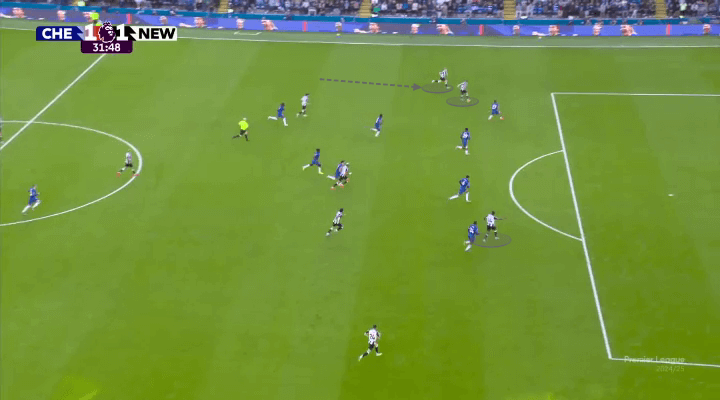

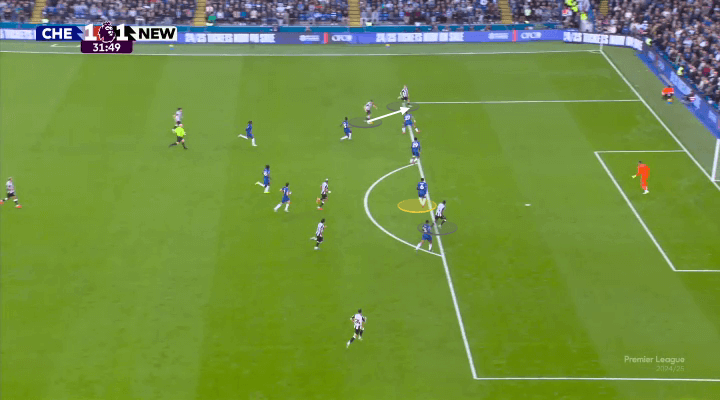

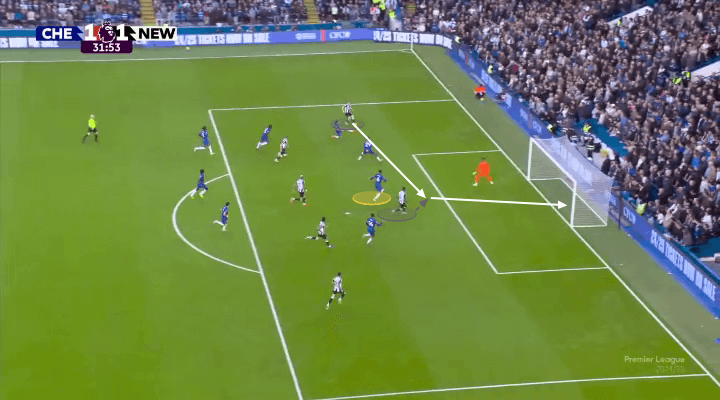

Here’s a concession against Newcastle. Anthony Gordon is on the ball, Lewis Hall is on the overlap, and Alexander Isak is the main goal threat in the middle.

Chelsea’s defence runs back with Isak, but again, as soon as they reach the edge of the box, Colwill freezes — look at him below almost cross-legged to stop his momentum. He’s played Isak offside, but the ball doesn’t go to him — it goes to Hall, who is just onside.

And when Hall crosses, Colwill’s split-second freeze on the edge means he can’t keep up with Isak, who just stays behind the ball and finishes.

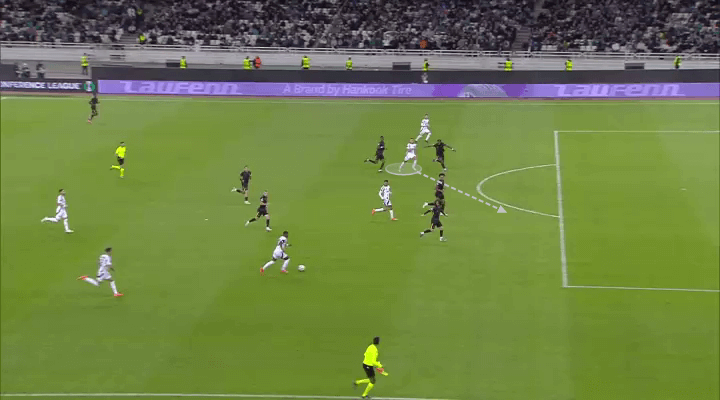

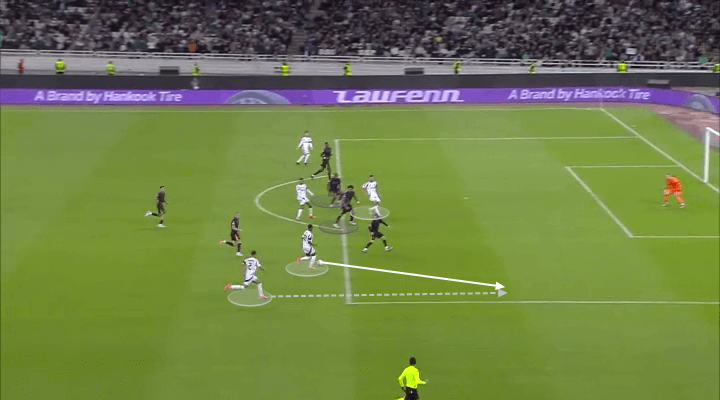

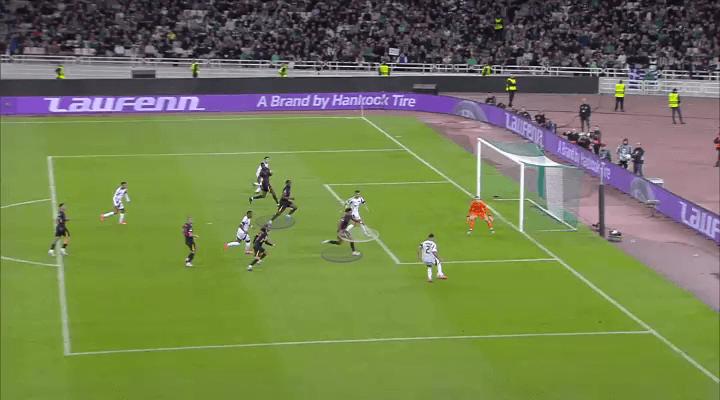

Here’s a very similar concession, away in the Conference League win at Panathinaikos. There’s a winger on the ball, a full-back overlapping, and Chelsea’s centre-backs are going to freeze as soon as they reach the box.

Full-back Marc Cucurella drops into the box, because he’s directly facing the dribbler, but the centre-backs halt their momentum briefly…

… and that means they can’t make up enough ground to get back and intercept the cross to the striker. In the end, the pass is turned in by the winger on the far side instead.

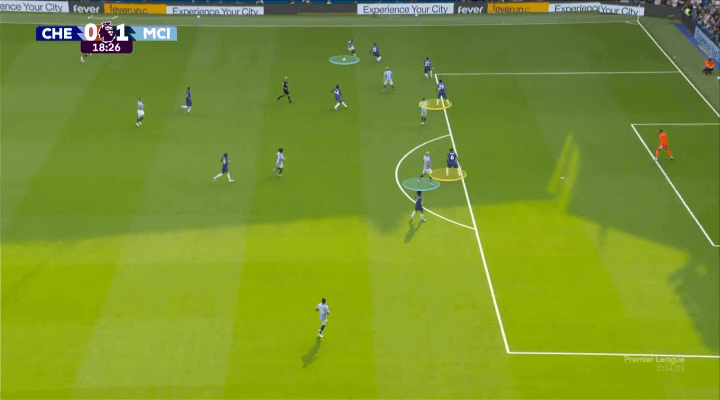

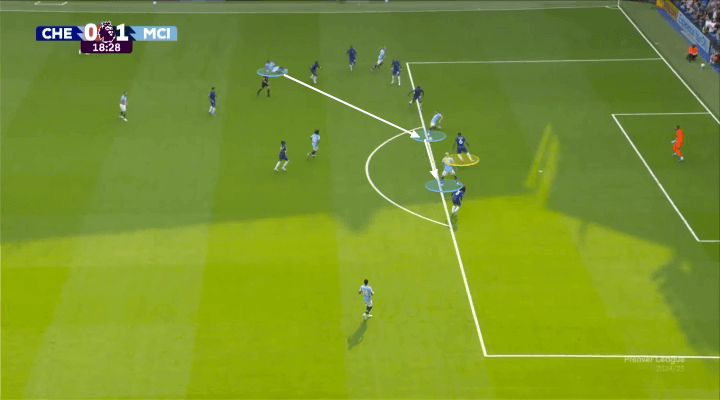

Here’s a concession to Manchester City in a 2-0 loss on the opening weekend of the season. Jeremy Doku is on the ball in an inside-left position, with both Bernardo Silva and Erling Haaland on the edge of the box. Chelsea hold their line as much as possible.

Doku then plays the ball into Bernardo.

Colwill waits until the last moment, then drops two yards as soon as Doku plays the pass. That means that he’s moving the wrong way when Bernardo diverts Doku’s pass into Haaland, and can’t intercept.

Haaland goes in behind and dinks home.

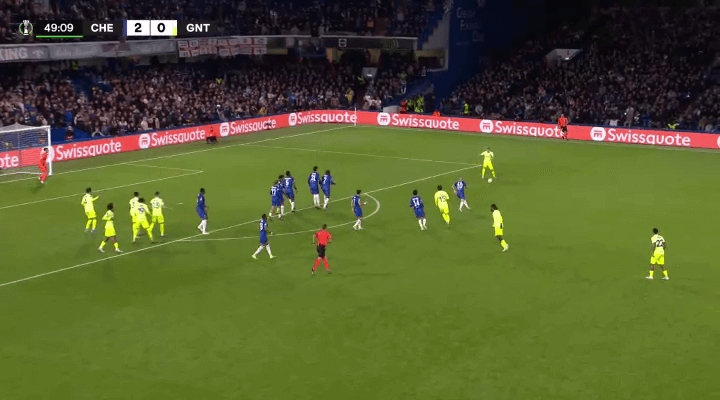

Here’s a different situation — the second phase of a set piece in the Conference League over Gent. But again, look at Chelsea’s players desperate to remain on the 18-yard line — as if the penalty box is made of lava — while opponents queue up at the back post.

Part of the problem is that it means defenders become static, because they’re so focused on standing still. Tosin Adarabioyo, the only man defending the far post against five players, is rooted to the spot and can’t turn quickly enough to challenge…

… and Chelsea concede.

It would be churlish not to point out that the Pellegrini offside trap, as it should be known, does have its benefits. It’s easy for the defence to remain in a flat line when trying to play offside.

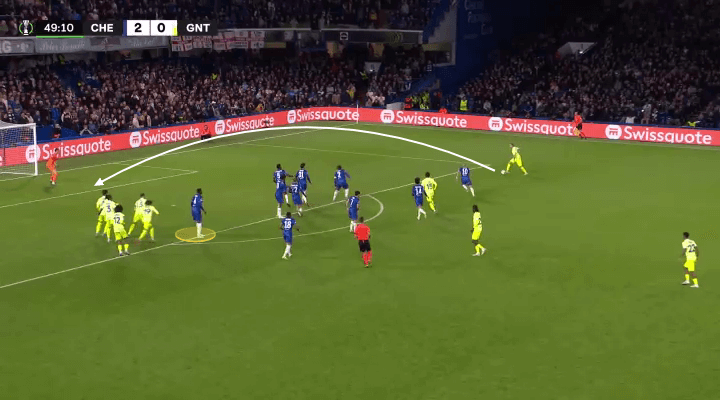

Mohammed Kudus’ disallowed goal in Chelsea’s win over West Ham was a good example, even if Enzo Fernandez had strayed too deep. Five other Chelsea players were organised in a good line.

But Chelsea’s defenders are surely capable of playing offside more conventionally; they did so against Liverpool, holding their line well to catch Salah offside for Gakpo’s disallowed goal.

And the irony of Kai Havertz’s disallowed goal at the weekend was that while Chelsea hadn’t got themselves organised and were caught out by this quick free kick, it was a good job the final defender wasn’t on the 18-yard line — he was a yard higher, meaning Havertz was offside.

Indeed, there’s a good chance that Havertz specifically positioned himself there because he expected Chelsea would be positioned, as they usually are, on the 18-yard line.

The Pellegrini approach has some merits — it didn’t prevent his City side from winning the title in 2014-15. But top-class opponents were often able to exploit the predictability of his defence with simple through balls and well-timed runs in behind — and that seems to be happening with Maresca’s Chelsea this season.

Top-class defenders must be capable of setting their own offside line, rather than working according to the geometry of the penalty box. If Maresca keeps on using this approach, Chelsea will keep on conceding simple goals.