On Day 1 of the 2024 MLB Draft, William Schmidt’s inner circle readied for a small gathering to celebrate what seemed inevitable. A right-handed pitcher out of Catholic High in Baton Rouge, La., Schmidt was a first-round pick waiting to happen.

Schmidt was technically committed to LSU, but even LSU head coach Jay Johnson knew better than to expect the teenage phenom to turn down a $3 million signing bonus — at minimum — to play college ball. One MLB scouting director called him “the most talented high school pitcher” on the board.

“Anybody that gets drafted in the first round signs,” Johnson told The Athletic.

Having long dreaded the looming threat that at least one of the 30 MLB teams would snatch his blue-chip pitcher, Johnson received a sudden text just hours before the draft began. All Schmidt sent was a picture. In an LSU hoodie and slacks, the 19-year-old held a stuffed animal Tiger.

Before family and friends could buckle their seatbelts on their way to the Schmidt household, the news broke: Schmidt would bypass the MLB draft, and stay committed to LSU.

Message boards were quick to credit the name, image and likeness (NIL) era of college sports, in which players are paid by school boosters through third-party collectives, as a major reason why Schmidt honored his college commitment. To Johnson, it wasn’t out of the question that Schmidt could have still landed at LSU in the pre-NIL era, à la Gerrit Cole and Mark Prior, who also went to college despite being drafted in the first round out of high school. Regardless, there is one distinct difference between those cases and this one: Schmidt can, and will, make a lot of money while living out his childhood dream.

Callin Baton Rouge! Time for another Natty🐅 pic.twitter.com/4ceMRwpMvg

— William Schmidt (@_williamSchmidt) July 14, 2024

An SEC recruiting coordinator estimates that Schmidt will make seven figures by the time he is draft-eligible again in three years. If the past three years serve as any indication, he won’t be the only one — and the ramifications of that new reality are now trickling up, and impacting the draft boards of MLB teams.

When NIL first swept across college athletics, baseball was largely an afterthought. A first-rate football player in the SEC could’ve been worth as much or more than the budget afforded to construct a school’s entire baseball roster. It’s still true in some cases, but the money being thrown around the diamond is no longer negligible.

“A lot of the rumors and things that you hear have slowly become true,” Tennessee head coach Tony Vitello said.

Multiple front-office executives for MLB teams said they had envisioned a world in which college baseball could compete for top talent, after the pay-for-play model took effect in the summer of 2021. It wasn’t until this past summer, three years removed, that this hypothesis proved true.

“This was the first year that we felt the real impact in the actual draft of guys just saying no to seven-figure bonuses,” New York Yankees assistant amateur scouting director Mitch Colahan said. “And you’re just kind of like, ‘That’s pretty crazy.’”

NIL has grown exponentially since its advent. Consider LSU baseball in 2023, the year the Tigers won the national championship. According to a person familiar with the program’s finances, the baseball NIL budget that season was about $1 million.

Eventual No. 1 overall pick Paul Skenes, an immediate-impact pitching transfer from Air Force at the time, received around $250,000, the source said, to play for LSU.

NIL budgets have risen since then. Absent NCAA regulations that separate true NIL deals from pay-for-play agreements, most budgets in SEC baseball now range from $1.5 million to $3 million, according to a head coach in the conference, who added that one program is working with as much as $4 million. Ryan Prager, a southpaw ace at Texas A&M, returned for his junior season after he did not sign as the Los Angeles Angels’ third-round pick in the 2024 MLB Draft. Per a source, Prager’s NIL earnings will be about $500,000, double what Skenes earned just two years ago.

On paper, a college player can make money through the commercial use of their name, image and likeness. In practice, it’s much more transactional. Players are regularly compensated by boosters to play for a certain school, which has effectively turned the college sports landscape into what a number of coaches have publicly criticized as the “the wild, wild West.”

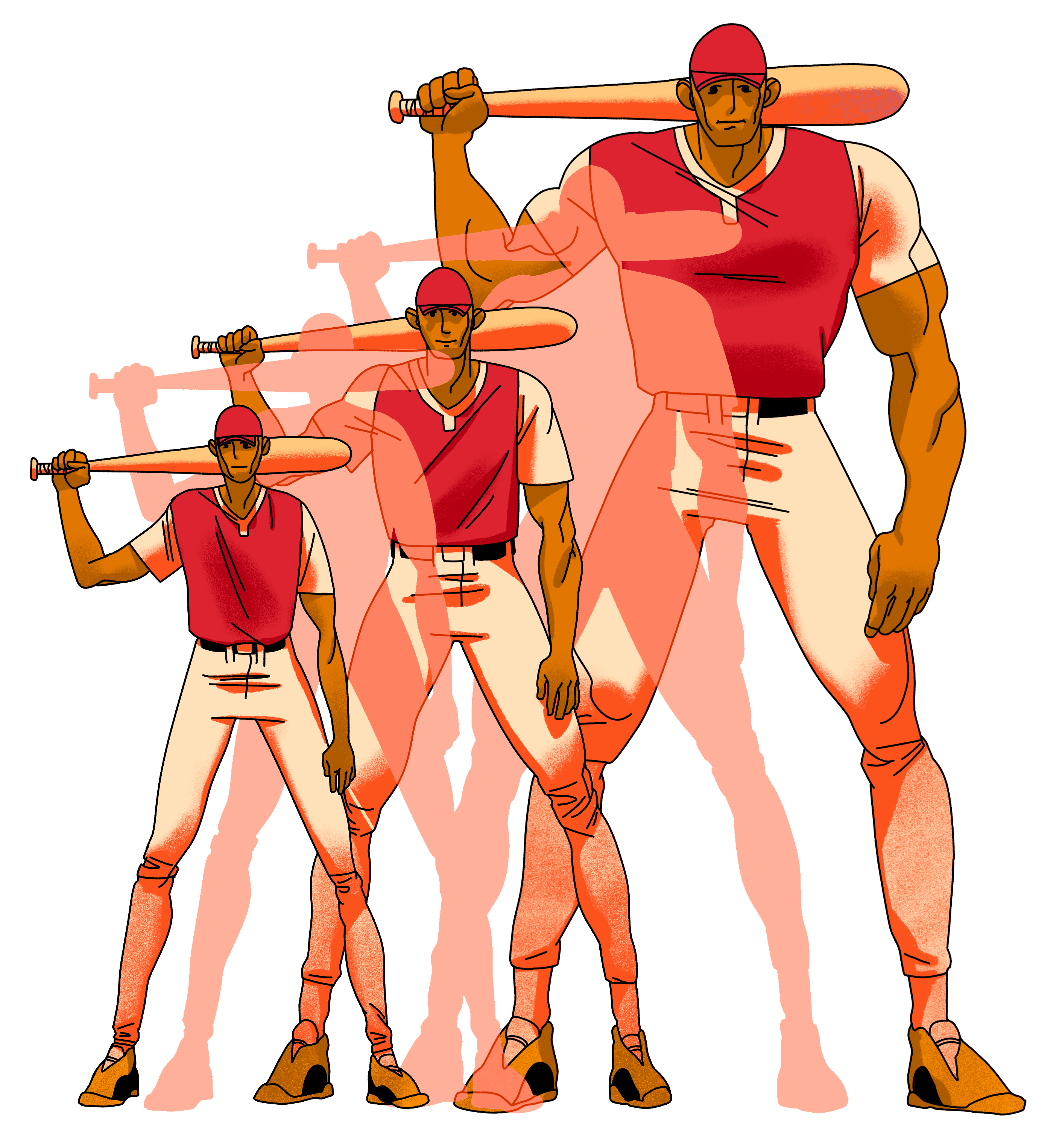

For elite talent, the NIL bonanza has in some cases made the college ranks a more lucrative destination than pro baseball.

“The thought would be that it would only be mid-to-late Day 2 and Day 3 that would be affected,” St. Louis Cardinals assistant general manager and amateur scouting director Randy Flores said. “But we are seeing as the resources have grown in the NIL marketplace, there is a real counter to what an MLB team can offer. And it’s part of the calculus now.”

Drafting players used to be more straightforward for MLB teams. A potential signing bonus was discussed with a player’s advisor beforehand. If both parties agreed, the player was drafted and soon thereafter signed for an agreed-upon sum. If not, the team could pivot to negotiate with the next player on its board. More often than not, a general manager could be sure that a player’s ask would not change overnight.

Thanks to NIL, that is no longer the case.

“Oftentimes, the NIL is fluid, and [college programs] can increase an offer and move the goalpost in effect and leave an MLB team with incomplete information at the time of negotiation,” Flores said. “… The kids now have a choice because it’s now more apples to apples rather than apples to something that’s not close to apples.”

MLB front offices are starting to feel the repercussions. Outside of the first round, for which the lowest slot value was $2,971,300 this past summer, SEC programs have the financial firepower to effectively outbid an MLB team even for an early-round pick.

“There’s 10 teams in our league, roughly, and I don’t want to speak for them or how they spend their money, but they have the financial means to quote-unquote ‘buy a player out of the draft,’ through their NIL,” Georgia head coach Wes Johnson said.

Texas A&M star outfielder Jace Laviolette, 20, wasn’t even eligible for the draft in July — players must be three years removed from college or 21 years old — but according to an amateur scouting director in the South, Laviolette as a junior this school year may make up to $750,000.

With that being the kind of money available to top college talent, multiple years’ worth of NIL could be comparable to a one-time professional signing bonus.

It is making a difference in the draft — the only question is to what extent. For only the second time since the start of the MLB Draft in 1965, all but one of the top-10 picks in 2024 were college players. The reasons depend on who you ask. Some say the shortening of the draft from 40 to five rounds in 2020, before 20 rounds became the new normal post-pandemic, has forced an unprecedented number of players to the college game. Others point to the contraction of the minor leagues. Then there’s NIL, and those who argue it has enabled college baseball to acquire more players and retain them longer.

They’re all correct.

Prospects lost to college baseball are more likely to enter the draft ready to make good on their signing bonuses, albeit at the expense of MLB teams’ preferred development plan. The 2023 MLB Draft featured a handful of top college players, including Skenes (No. 1), LSU outfielder Dylan Crews (No. 2), Florida outfielder Wyatt Langford (No. 4), Grand Canyon shortstop Jacob Wilson (No. 6), Wake Forest right-handed pitcher Rhett Lowder (No. 7) and Florida Atlantic first baseman Nolan Schanuel (No. 11), all of whom have already made their major-league debuts.

For signing bonuses that ranged from Skenes’ $9.20 million to Schanuel’s $5.25 million, each team received a quick return on investment.

“Professional baseball organizations are relying on college baseball to develop their players at a rate higher than ever,” Jay Johnson said.

For years, MLB teams feared the point where NIL might encroach on their domain. Now it has, and the resources afforded to college programs will only increase. In accordance with House v. NCAA, a historic lawsuit settlement earlier this year that opened the door for schools to share revenue directly with athletes, college baseball teams by 2025-26 will be allowed to offer up to 34 full scholarships for the first time in the history of the sport. This, in addition to NIL, could force front offices to further rethink their approach to player acquisition and development.

“We have to be able to sell ourselves,” said Colahan, who’s worked in the Yankees’ amateur scouting department for a decade and counting.

“We used to be able to offer a signing bonus and a scholarship, where colleges could only offer a limited scholarship. Now it’s definitely a more level playing field because they have NIL, they have more scholarships if they’re funding them and you just got to be able … to prove to them that they’re walking into a situation that’s going to make them better.”

Colahan pointed to Schmidt, Prager and high school shortstop Tyler Bell as three prospects whose expectedly high NIL profiles seemed to leave a mark on the 2024 MLB Draft. Schmidt withdrew his name the day of the draft to fulfill his LSU dreams. Prager stiffed the Angels, and his $948,600 slot value, for Texas A&M. And Bell, drafted No. 66 overall by the Tampa Bay Rays with a $1,260,200 slot value, recently wrapped up his first fall ball at Kentucky.

How much more bargaining power may yet be in store for players to draw from?

“It’s just scratched the surface this year, really,” Yankees amateur scouting director Damon Oppenheimer said.

Three years ago, MLB decision-makers ruminated on NIL worst-case scenarios. Three years from now, no one knows for sure how it might evolve. But today, MLB executives and college coaches alike acknowledge that college baseball programs have been empowered to vie for some of the best young talent the sport has to offer.

Opinions vary on whether such a reality is for better or worse. Regardless, it’s here.

“We’ve hypothesized over these possibilities of this type of stuff, and now it’s real,” Colahan said. “So we got to learn to live with that.”

The Athletic‘s Sam Blum contributed to this story

(Illustrations by Avalon Nuovo for The Athletic)