“I’m not going to use any names but, there’s been lots of players over my career where analytically, you’re going ‘What’s he doing on our team?’” Scott Arniel told The Athletic this September. “And then you go: ‘I need this guy on my team.’

“It might be as simple as the dressing room. Maybe that’s a guy we need to have in our dressing room. Maybe there’s a certain element that he has that you just need on your hockey team.”

I couldn’t help but think of that quote when Logan Stanley fought Mark Kastelic in the aftermath of David Gustafsson’s injury against Boston on Tuesday night. Trent Frederic challenged Gustafsson to a fight after Winnipeg’s 6-1 goal; Gustafsson accepted and was immediately hurt, cut open by Frederic’s first punch. The Jets were incensed. Frederic is a good hockey player and the Bruins put him on the ice following multiple Jets goals during Winnipeg’s 8-1 win. But Winnipeg’s players have a good sense of which Bruins do and don’t fight.

Gustafsson had zero fights in his career before the one that injured him. Frederic had 38. Gustafsson missed practice on Wednesday and is now in concussion protocol. It was a mismatch that Gustafsson was in an awkward position to accept and cost the Jets. Stanley stepped up, fighting Kastelic, and then, when the game was over, Mark Scheifele awarded Stanley a jacket to celebrate his efforts.

Stan and Chibi earn the jackets! 🧥 @Bell_MTS | #GoJetsGo pic.twitter.com/pRcy0BsBi4

— Winnipeg Jets (@NHLJets) December 11, 2024

Stanley isn’t an analytical darling. His size and willingness to use it may be keeping him in the Jets lineup more than his abilities at five-on-five. Multiple Jets coaching staffs have decided they want Stanley on their roster or in their lineup, sometimes at the expense of other young defencemen like Declan Chisholm or Johnathan Kovacevic.

Strengths in one area can be weaknesses in another. The Jets would be better served if the player performing Stanley’s job in that situation had the on-ice impact of Dustin Byfuglien or Chris Pronger — or more realistically, Jamie Oleksiak or Chris Tanev.

But Stanley can’t control the Jets’ roster or the minutes he gets. He’s taken too many penalties and shown mobility issues at even strength. And he’s stepped up, earning the praise of his team’s biggest stars.

Using Stanley’s performance as inspiration, today is a day to reflect on Winnipeg’s biggest strengths and weaknesses. Thirty games into the season, the Jets have given us a lot of highs and a few lows to investigate.

1.040: Winnipeg’s league-leading shooting and save percentages

There is a simple stat called “PDO” that people in the analytics community often use as a measure of luck. The letters “PDO” don’t stand for anything. They’re a reference to a blogger named Brian King. His idea was that, if you add a team’s shooting percentage to its save percentage and get a number much bigger than 1.000, then that team might be enjoying an unsustainable run of luck.

The Jets have the third-best shooting percentage in the NHL (12.69 percent) and the second-best save percentage (.913). Add them together and Winnipeg’s “PDO” is 1.040 — tied with Washington for the league’s highest number.

So what, Murat. You can’t just invent numbers and then say they’re important without saying why.

Honestly: good point. My opinion is that we need to pay attention to the Jets’ shooting and save percentages because those numbers are among the most volatile and impactful stats in hockey. The sport is chaos as a general rule. Goals win games and depend partly on talent and partly on traffic, deflections, and two inch posts: In the wrong circumstances, even the best goaltender on the planet can put up an .870 save percentage in a sample size as small as five games.

It’s hard to sustain extreme highs or lows in the long run, though. A goalie’s save percentage tends to regress toward their career average. The same applies to shooters. If Kyle Connor goes 15 shots in a row without a goal, it doesn’t mean he’s forgotten how to shoot.

Still, some people are going to throw Winnipeg’s 1.040 PDO around and claim that the Jets’ run to the top of the standings is all about luck. I think that’s too simple — and that digging into it reveals a source of Jets strength. Winnipeg’s save percentage from 2021-22 through 2023-24 — the three seasons before this one — was .912. With Hellebuyck in net, a .913 isn’t unsustainable. It’s the norm to which hot or cold streaks regress — and it’s better than most teams because Hellebuyck is better than most goalies.

Winnipeg’s shooting percentage would be a concern, though. Are the Jets leading the league in goals because of some unsustainable run of shooting luck?

Yes, but only on the power play, which is running neck-and-neck with Hellebuyck for the title of Winnipeg’s biggest strength through 30 games. Winnipeg is taking an average number of shots and scoring an average number of goals at even strength, riding Hellebuyck’s excellence to a 61-48 lead in goals. Winnipeg’s top line, centred by Scheifele, is winning its minutes 21-17 despite getting outshot.

Getting outshot is not a new idea for Scheifele. Neither is the idea of Winnipeg scoring on a higher-than-average number of shots when he’s on the ice. He tends to finish among league leaders in “passes to the slot” and has finished with a higher share of goals than shots in every season in his career but one.

“I’m a guy that, my whole career, I’ve played a possession game, especially in the O-zone,” Scheifele once told me. “I like to hold on to the puck, especially below the goal line. That’s kind of where I create my offence. And then go to the slot when I play with some pretty magical players that can find me in the slot. That’s always been my game.”

There have been times when Connor, Scheifele, and Gabriel Vilardi have given up so many shots — or so many quality transition scoring chances — that it’s let the air out of their offensive success. They’re winning their minutes on the whole, though, and they haven’t needed unsustainable shooting percentages to do it.

One area of concern? The Jets’ power play is scoring on a higher percentage of its shots than the best power play in NHL history. Scheifele, Connor, Vilardi, Cole Perfetti, Nikolaj Ehlers, Nino Niederreiter, Neal Pionk, and Alex Iafallo are all scoring on at least 20 percent of their shots. That’s not sustainable, no matter how much variety the Jets have added to their power play this season, and it leaves room for concern. The Jets scored just one power-play goal during their recent four-game losing streak. A mini-slump of that nature is entirely normal and, while the Jets were struggling in other areas of the game during that slide, it illustrated how quickly things can go south for a team that dominates by its power play and goaltending. That’s true even when those are real strengths.

Wait, did you lead with “the Jets are lucky” just to end with “they’re only lucky in specific ways?”

Yes. If you want other signs of luck, you can find them in the Jets’ seven goals with their goalie pulled — second-most in the league despite the league’s second-best record — or their perfect 4-0 record in overtime. I think Winnipeg is an average five-on-five team with good finishing, great goaltending, and an elite power play that might sometimes run cold because that’s what power plays do.

77.6 percent: Winnipeg’s PK success rate and its most costly weakness

The Jets’ power play exploded for three goals against Boston, improving that special teams area to 30.4 percent — the second-best rate in the NHL. It was a much-needed outburst from a unit that’s struggled to maintain its pace without Ehlers. It was also a reminder that the Jets’ power play is helping the team more than their penalty kill is hurting it — even as we watched David Pastrnak strike back on the power play for the Bruins’ only goal. Winnipeg’s special teams are +13 on the season.

The penalty kill is still a problem. Winnipeg’s 77.6 percent efficiency rate is 22nd-best in the NHL. Three shorthanded goals help the team to a shorthanded goal differential of “only” -14, despite 17 goals against — tied for ninth-best in the NHL.

What’s going poorly?

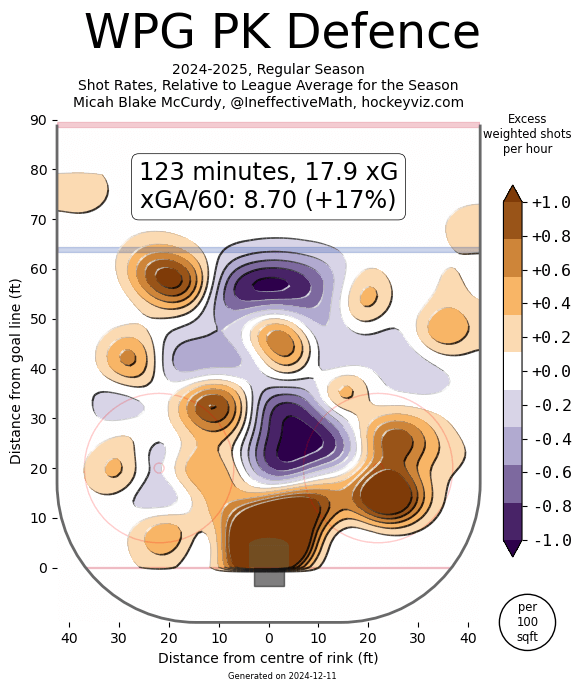

Winnipeg’s PK gives up a ton of shots from most parts of the defensive zone. It gives up a disproportionate number of those shots from the most dangerous areas of the ice — the low slot and all around the crease. If this sounds familiar, it’s because it was a problem last season as well as poor faceoff percentages, failed clears, and struggles to clear the net front kept Winnipeg in its own zone for 62.3 percent of its PK minutes — well below league average.

The Jets continue to struggle in the faceoff circle; they’re the third-worst shorthanded faceoff team, despite average results on the power play and at five-on-five. Adam Lowry has taken the lion’s share of PK faceoffs, typically drawing the opponents’ top unit, and struggled to a 34 percent win rate. Rasmus Kupari has managed to win half of his 40 shorthanded faceoffs so far this season — Winnipeg’s best number — but is typically the Jets’ second option.

The problems go well beyond the dot, though. I see it as a combination of two things — a lack of overall pace and an inability to win battles in the crease. The latter is easier to quantify: the Jets have given up the third most rebound shots on the PK, despite being one of the league’s most disciplined teams.

A rebound needs an initial shot. Winnipeg gives up the fourth most unblocked shots per minute on the PK. It needs a goaltender to leave a rebound; Hellebuyck has obliged. And it needs the attacking team to beat the Jets’ PK to the loose puck.

Here’s a map from Hockey Viz. If an area is red, Winnipeg gives up more shots than average from that spot — and that’s the trend, on the whole.

Dylan DeMelo is doing what’s asked of him here, but he’s not fast enough to get into Pastrnak’s shooting lane (although his stick accidentally contributes to the goal.) Pastrnak ends up with time and space — and he’s one player whose time and space is most troubling, from a Jets perspective.

David Pastrnak with a trademark PP one timer to cut the Jets lead to 3-1. McAvoy to Pasta at the elbow is how this PP is supposed to look pic.twitter.com/UFEfEY85l9

— Boston Bruins Watcher (@WatcherBruins) December 11, 2024

Based on my understanding of the Jets penalty kill, DeMelo is correct to take Pavel Zacha in front, correct to release him to Vladislav Namestnikov, and correct to stay net front until the pass gets to Charlie McAvoy at the top of the zone. The moment McAvoy gets the puck, Pastrnak is a threat and you can see DeMelo racing out into his shooting lane. That’s the ask of Jets defencemen in that situation: get in the lane. It doesn’t work out, DeMelo looks slow, and it’s easy to wonder why he didn’t leave the net front earlier to cheat into Pastrnak’s lane.

The problem with that is Elias Lindholm has a lane to Zacha in the middle of the ice and Zacha has positioned himself below Namestnikov in the slot. If DeMelo abandons the slot, then Zacha is alone with a lane to the net. If DeMelo pops up to take Zacha and Namestnikov cheats up on McAvoy, then Lindholm and Brad Marchand have seam passes available to Pastrnak.

My read, then, is that Connor and Stanley give up a lot of space in their attempts to be aggressive on Marchand and Lindholm. It’s also that DeMelo is slow to get into the lane when the pass ultimately reaches its intended target. I’d also like to leave a little bit of room for Pastrnak being an elite shooter who gets a good bounce off of DeMelo’s stick.

The whole sequence seems a bit too easy, from the Bruins’ puck recovery off their initial missed shot through Pastrnak getting the puck with DeMelo a half step slow to step into the lane. Winnipeg’s defencemen are slower than the NHL average as a rule, based on NHL Edge data, so I wonder if that half step is unavoidable. I also tend to credit PK forwards for reducing shot quantity by virtue of their speed and outside pressure, while crediting defencemen for impacting quality by tying up sticks and fighting for rebounds in front of the net.

That’s an oversimplification but it’s worth noting that the two Jets forwards who have been on the ice for the fewest shots per PK minute are Connor and Kupari — two of the Jets’ fastest skaters. The two Jets defencemen who have been on the ice for the fewest low slot chances per minute are Dylan Samberg, who is an excellent all-around defender, and Stanley, who is the Jets’ biggest defenceman.

It’s possible that Winnipeg’s PK system is fine but doomed to failure until its forwards get faster or its defencemen get better at clearing the net. Samberg’s importance is well felt, too. I’m tempted to look at the multiple years of struggle and conclude that it’s about personnel, not the Xs and Os, while thinking the Jets might get better results from using Connor, Kupari, and other speedsters even more than they do.

And I think a veteran defenceman who can impact the PK and play top competition at five-on-five, too, would be a brilliant trade deadline acquisition.

(Top photo of Connor Hellebuyck and Neal Pionk: Matt Marton / Imagn Images)