Two games, two wins, six points, four goals, two clean sheets.

Those were the statistics after two of England’s Under-21 European Championship group games last summer, and it’s precisely the same for the senior men’s side after the opening couple of Nations League results this season.

The uniting factor of those teams is Lee Carsley, the head coach of that under-21s side, and the man who a couple of weeks later guided England to a first Euros title in that age group since 1984. And after Gareth Southgate’s resignation in July, Carsley stepped up as interim head coach of the senior team.

There is an easy temptation, especially as far as style goes, to compare different teams under the same manager/coach.

But a quirk of this international break is that Carsley called up five players who were in that victorious squad under him last June and July: Angel Gomes, Noni Madueke, Levi Colwill, Morgan Gibbs-White and Anthony Gordon, though the latter had been part of Southgate’s Euro 2024 campaign in Germany.

With just under two years to the next major international tournament, and England in a relatively easier Nations League group after being relegated to its second tier last time out, this window provided an opportune moment to promote young talent. After all, this was the first international break of the season, and there are few chances for the same coach to move with players across age groups.

Carsley’s explanation for squad selection was that, compared with Southgate’s arrival, also from the under-21s on an initial interim basis, in 2016, “it’s totally different now. They’re used to competing”.

The Southgate era can be condensed into the success of three semi-finals across his four major tournaments, plus reaching the final in two editions of the European Championship. The criticism of those eight years relates to repeated defeats to technically superior sides, often stemming from a lack of control in midfield.

Which is why, when asked about his desired style, Carsley did not speak of a personal philosophy but rather evolving what was already there. “We’ve tried to get three or four different ways of playing,” he said before the Republic of Ireland game in Dublin last weekend. “It’s not about my style or way of playing — coaching is about utilising players’ ability and strengths.”

The team in these first two Nations League games was built around a front four, with high-and-wide wingers in Gordon and Bukayo Saka to stretch the play against deep opposition blocks. Those roles added balance for Harry Kane, who won his 100th cap against Finland last night. Kane is a player who likes to drop in, and he added support around Jack Grealish as the latter played as a No 10.

There was notable fluidity in England’s build-up, with Trent Alexander-Arnold mixing between midfield and right-back in both fixtures. Rico Lewis fulfilled a similar role against Finland from the left, although when Colwill started at left-back in Dublin at the weekend, he operated as a third centre-back.

The rotations and the combinations depended on the profiles, not the other way around. Gordon called the win in Ireland a “really good showcase of positionless football, in a sense. People could pick the ball up wherever” when speaking to ITV, the game’s UK broadcaster.

England weren’t without structure though, attacking more through interchanges of positions than anything else. Most of the time, they were attacking in the 3-2-5 formation which is synonymous with top European sides, and similar to England Under-21s’ lop-sided build-up under Carsley.

Against Ireland, Colwill stayed deep, Alexander-Arnold joined Kobbie Mainoo as a second No 6, and Declan Rice pushed on to create a front five.

The strength that day was the Alexander-Arnold and Gordon combination, with the Liverpool man’s long passes consistently finding the Newcastle winger in-behind, exploiting Matt Doherty’s aggressive defensive positioning for the home side.

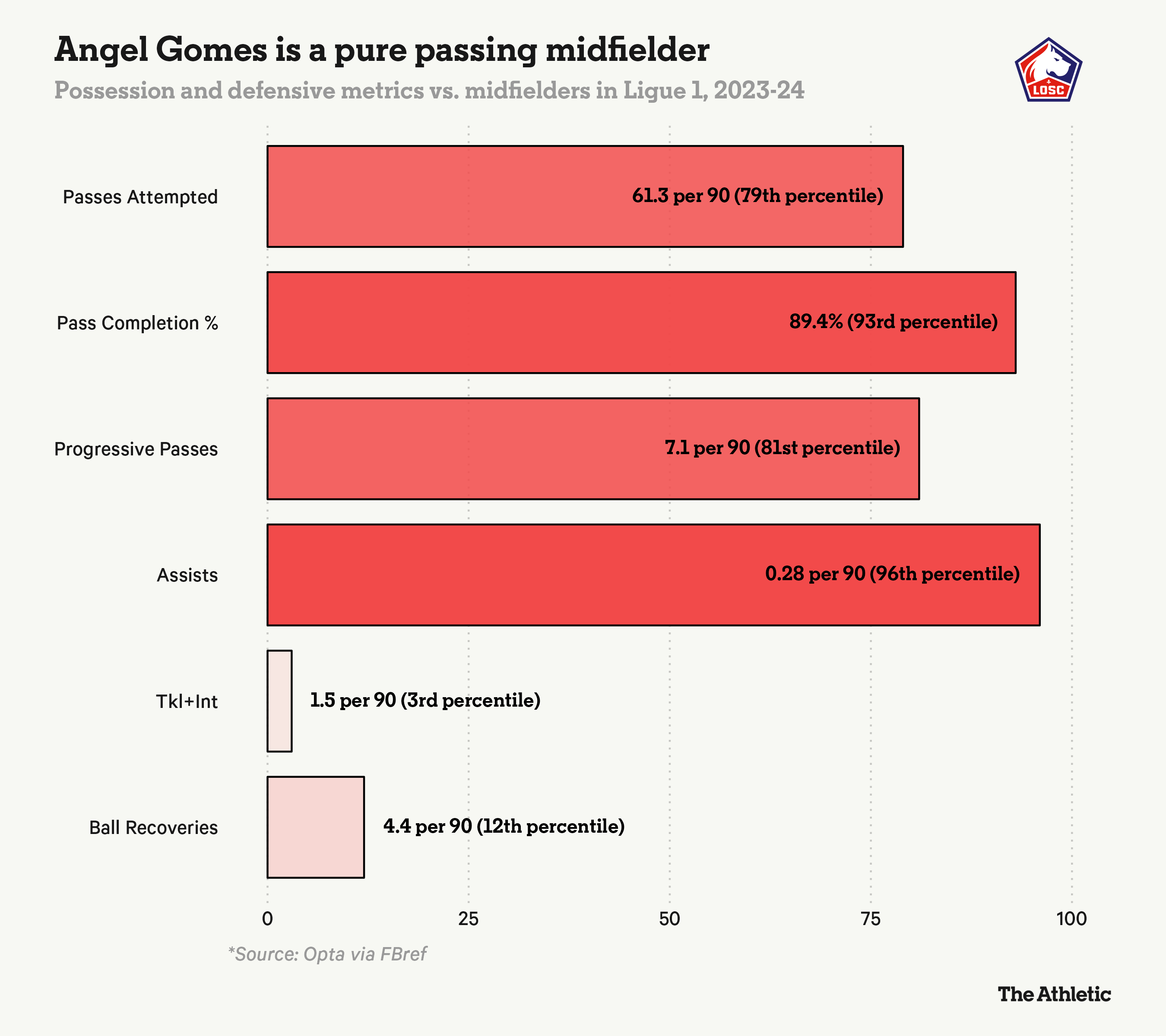

In the Finland win, the midfield profiles changed, and England saw the latest potential solution to the burning question: who should be the third midfielder with Rice and Jude Bellingham? This time, it was Angel Gomes, unique not only for playing in France’s Ligue 1 (with Lille), but for how he operates as a No 6.

1992 – Angel Gomes will be the first player to start for England while playing for a French club since Marseille’s Trevor Steven in June 1992 (v France). Renaissance. pic.twitter.com/11SHsYsDbS

— OptaJoe (@OptaJoe) September 10, 2024

“He is probably different to what we’ve (England) seen in the past in terms of the central midfielder that is a little bit more physical, more robust,” Carsley said when announcing the squad. “Angel is very technical, he controls the game with his skill and technique. Tactically, he is excellent.”

Southgate either prioritised or always made room for defensively-solid and high-work-rate No 6s — Jordan Henderson, Conor Gallagher, Eric Dier, Ruben Loftus-Cheek, Kalvin Phillips. Carsley’s inclusion of the 5ft 6in (168cm) Gomes speaks to the culture shift that England need to win a major final for the first time since 1966. He said last week that the “standards are so high, that last push is the hardest thing”. Part of the failure, under Southgate and in decades prior, had been an inability to control the midfield with possession, England for so long a country consistently lacking in technicians.

Against Finland, the 24-year-old Manchester United academy graduate had the most touches (130) of any starter in Carsley’s side, and completed the most passes — 116 of his 124 (94 per cent), making him the first England player to complete more than 100 passes on their full debut (since that data was first collected in the 2008-09 season). A significant proportion of these were low-risk, but it showed how Gomes can change the point of attack and help tire defences by forcing them to shuffle.

Only four of Gomes’ passes were long, but there were plenty of instances of smartly disguised balls that broke lines, including one in the first half, on the half-turn, which ricocheted through to Kane, who forced a save from Lukas Hradecky.

Gomes’ short-passing style, particularly contrasted to Alexander-Arnold’s directness, meant last night was never going to be the type of win England had in Dublin. Even though England beat Ireland and Finland by the same scoreline, they were two remarkably different ways of winning 2-0, even if they faced a 5-4-1 mid/low-block in both matches.

While they raced into an early lead on Saturday, which opened the game up, Finland made sure they kept their wing-backs deep last night at Wembley to minimise one-v-one situations for Saka and Gordon, who were forced to dribble more to create crossing chances. When England did create situations to deliver, they often had to target the back post, because it was the only way they could get space and an overload, which forced the wingers to cut back in onto their dominant foot.

England attempted 29 crosses against Finland (seven found a team-mate), over twice as many as in the Ireland win (13), and had to hit plenty of switches as the centre of the pitch was packed out.

If this is an audition for Carsley to get the job permanently, it was another indication, as with the under-21s last summer, that he can balance attacking style with defensive substance.

There are defensive transition issues to iron out, which showed particularly against Finland, as England’s heavy-rotational structure often stretched the distances between team-mates and meant the structure behind the ball was skewed. They struggled to counter-press, and Finland escaped on several occasions in the first half, only for their counter-attacks to break down due to errors.

It was a reminder though that even if Gomes is the beneficiary of injuries to others and good timing in terms of his selection for this squad, England’s hopes for a senior men’s trophy will rest on their ability to win the technical battle in midfield.

It has to start somewhere. And maybe it just has.

(Top photo: Michael Regan – The FA/The FA via Getty Images)