A clear aspect of how Enzo Maresca wants Chelsea to play revolves around the use of his wingers.

In the Premier League this season, Chelsea have mainly played in a 3-2-4-1 shape on the ball, with the widest players deployed as ‘proper’ wingers.

Excluding the first game against Manchester City, where Malo Gusto provided the width down the right side, and the victories against Leicester City and Southampton, where Marc Cucurella did the same on the other wing, Chelsea’s widest players have been Noni Madueke, Pedro Neto, Jadon Sancho and Mykhailo Mudryk.

Maresca’s preference is clear and it makes sense considering the profiles of his wingers, who thrive in one-versus-one situations. Earlier this season, he told Chelsea’s website about wanting his wingers to isolate defenders and explained why that is an important element of his strategy.

“Most of the time, our wingers have the chance to be one-v-one 10 times during the game,” said Maresca. “For every winger, it’s a dream come true to play forward and have the chance to go one-v-one. We allow them during the game to go one-v-one at different times.”

Achieving this is easier said than done, but this season Chelsea have successfully managed to do so on multiple occasions. One way they do it is by pulling the opponents in one direction, before switching the play to the other side while using the No 10 who is near the winger to further isolate the wide player.

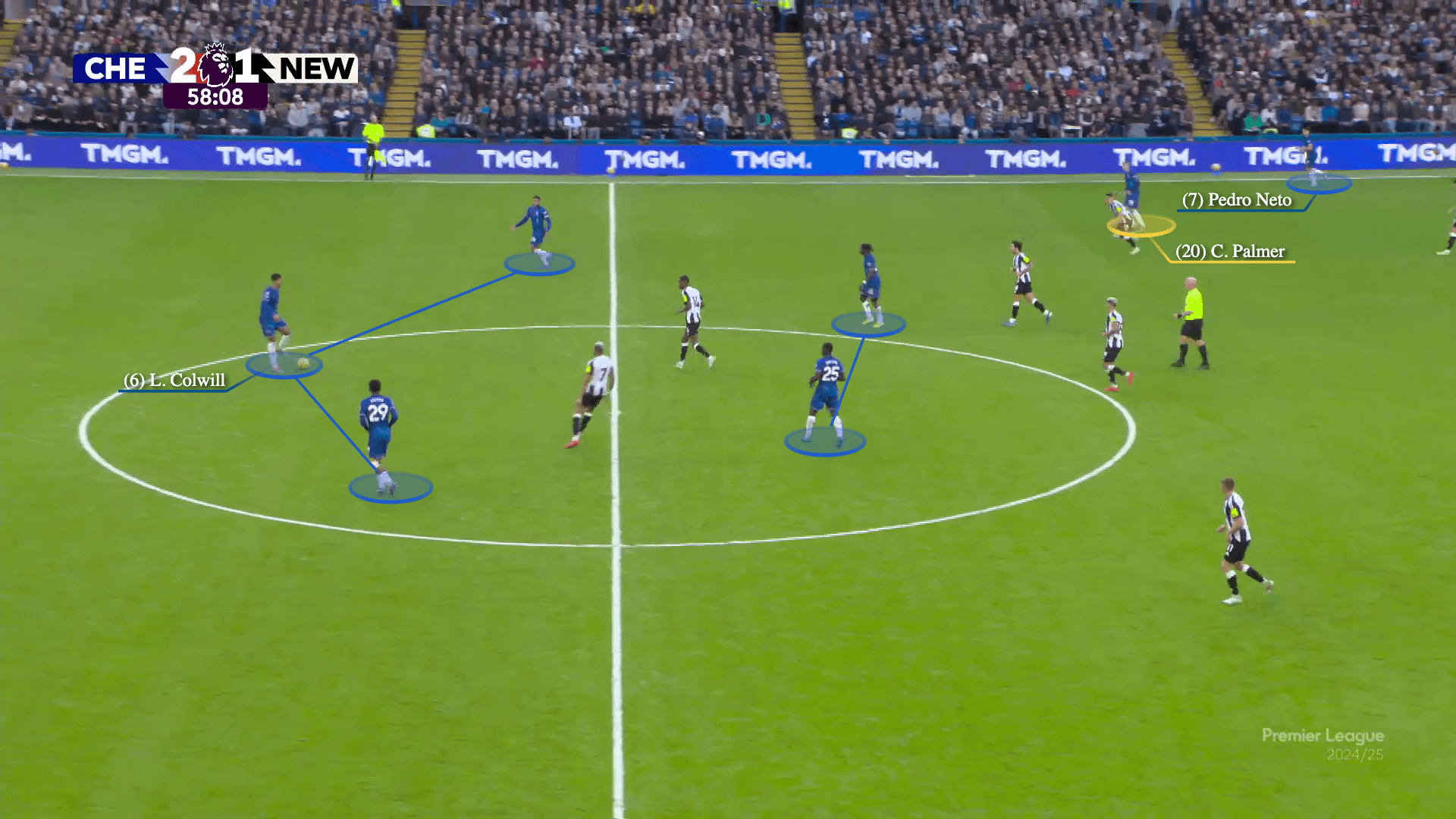

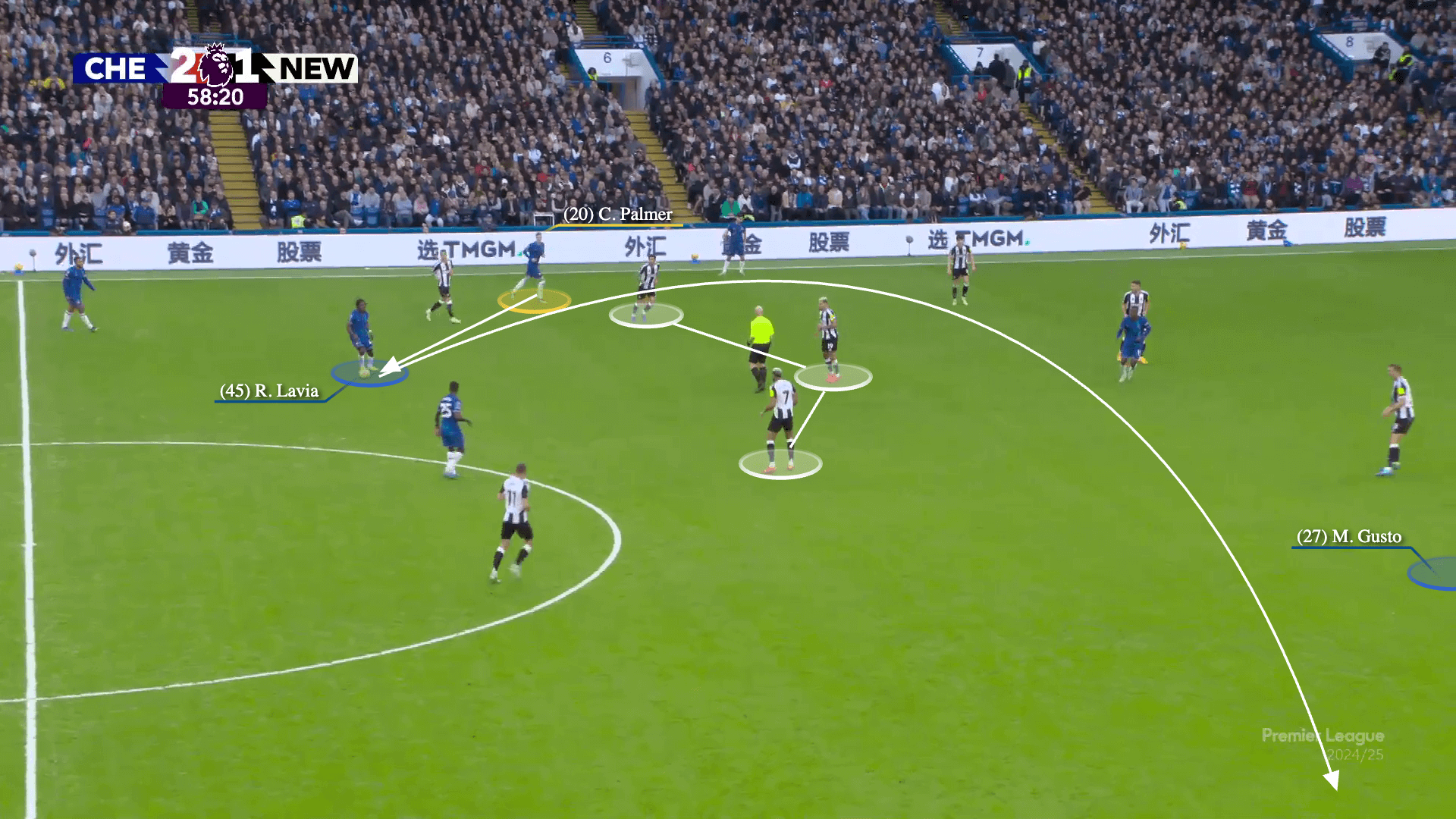

In this example, from the 2-1 victory against Newcastle United in October, Chelsea are building up the attack in their regular 3-2 shape with Cole Palmer playing as the left-sided No 10.

To progress the ball up the pitch, Palmer drops towards the touchline when Levi Colwill plays it to Reece James, with Pedro Neto making a run behind Newcastle’s right-back.

This way Palmer is free to receive the ball because Tino Livramento has to drop with Neto, and Miguel Almiron is already moving up to press James.

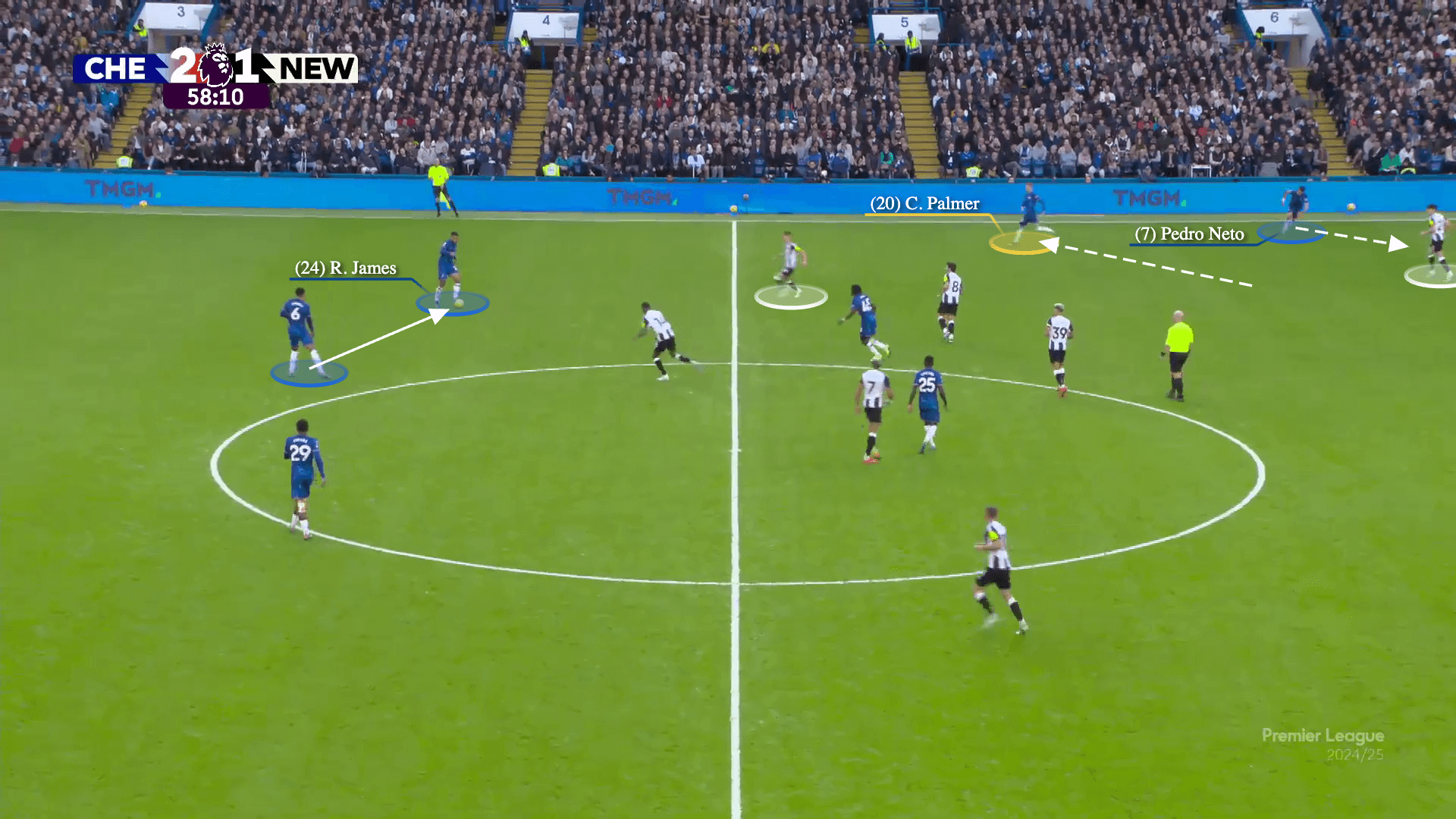

But James easily finds Palmer down the left wing…

… and Newcastle’s midfield three have to shift towards that side to defend against Chelsea’s attacking midfielder.

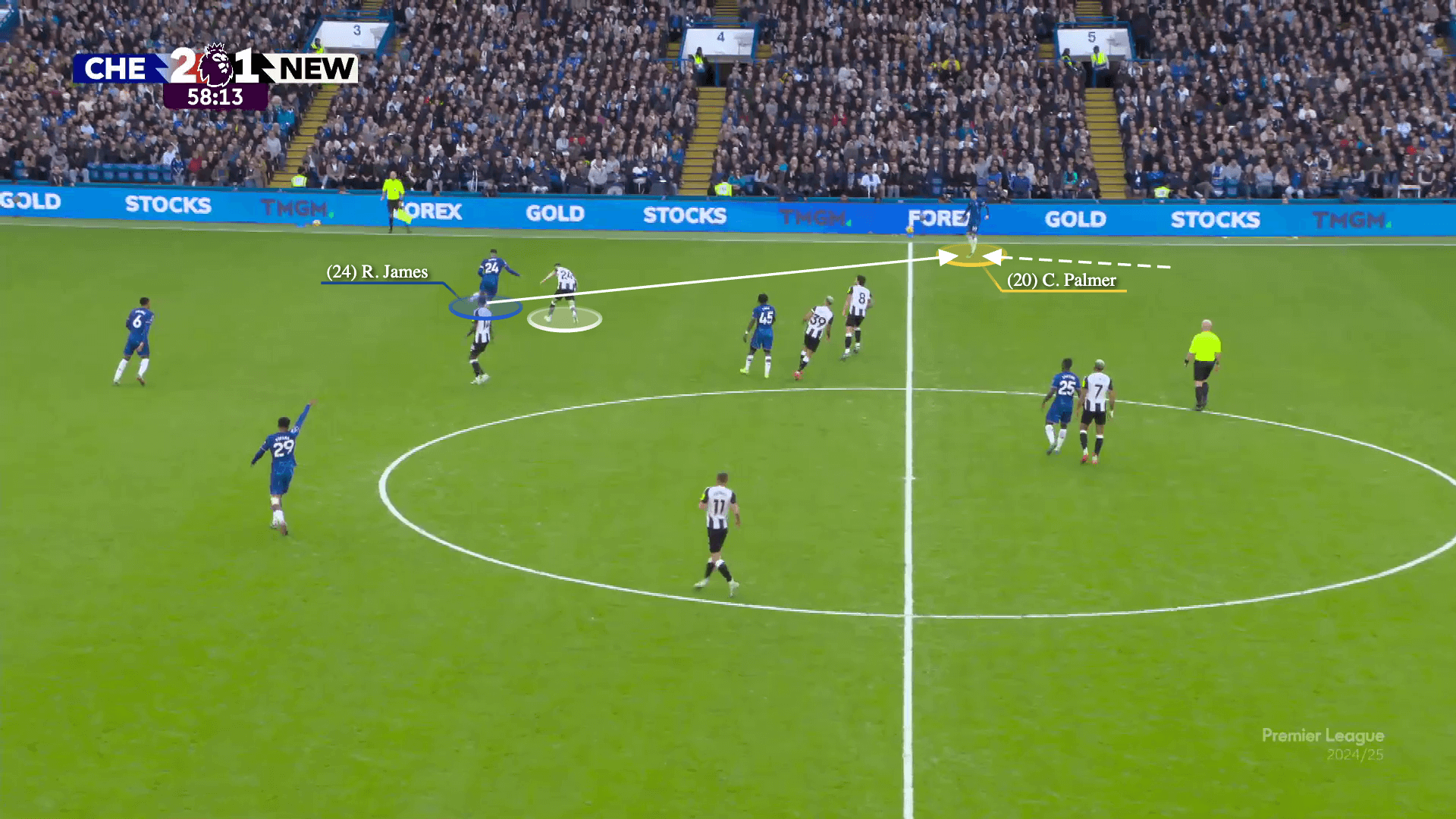

Palmer then plays the ball back to Romeo Lavia and the midfielder switches the play towards Madueke, with Newcastle’s midfield and left centre-back not in a position to protect their left-back.

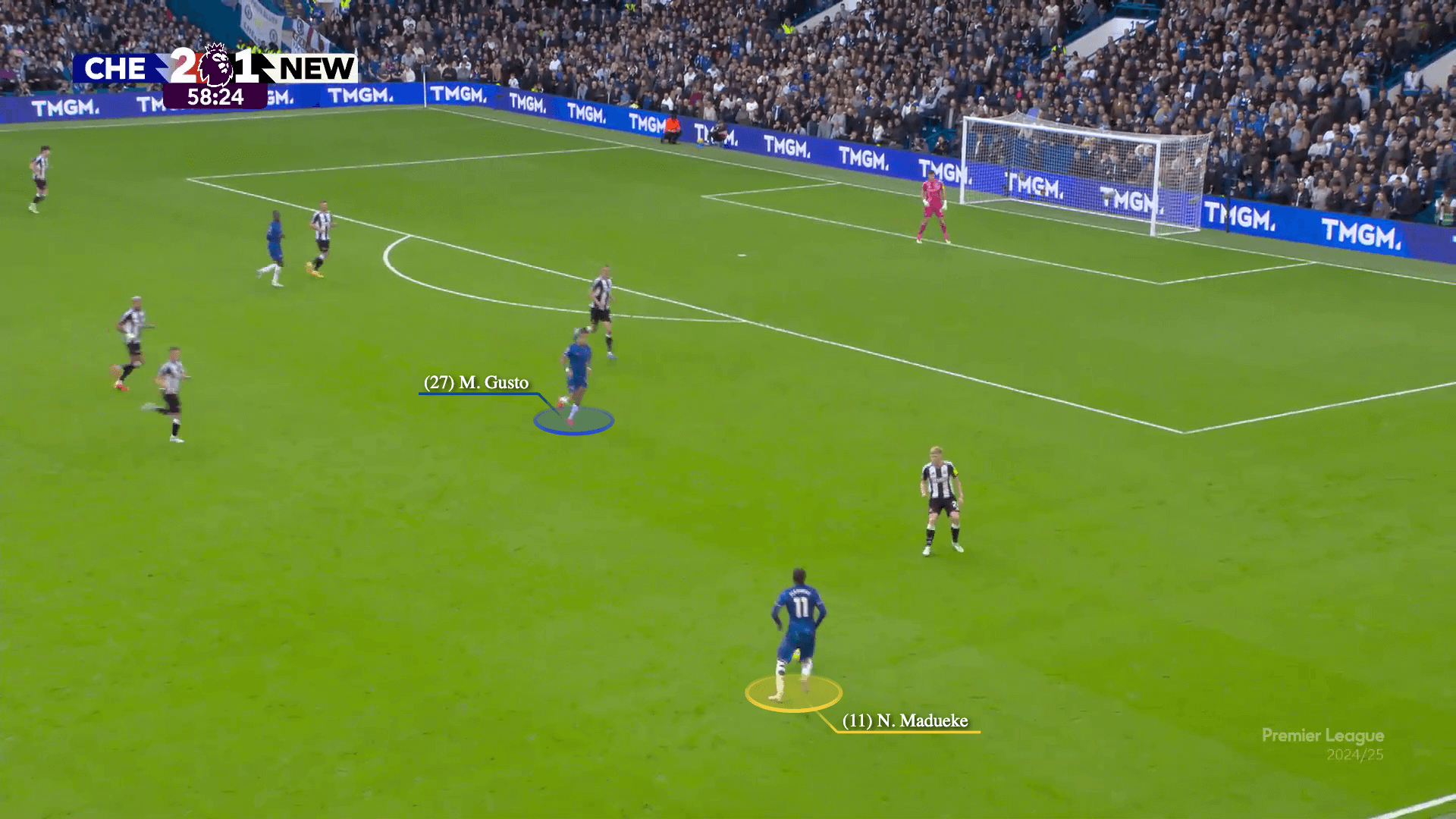

Gusto’s role in possession as the right-sided No 10 means that Newcastle’s left centre-back, Dan Burn, can’t move across to support his left-back when Chelsea switch the ball to Madueke down the right wing.

Despite achieving the target of putting Madueke in a one-versus-one situation against Lewis Hall, Lavia’s pass is played behind the right winger, which means that the isolation scenario isn’t happening in a dangerous zone.

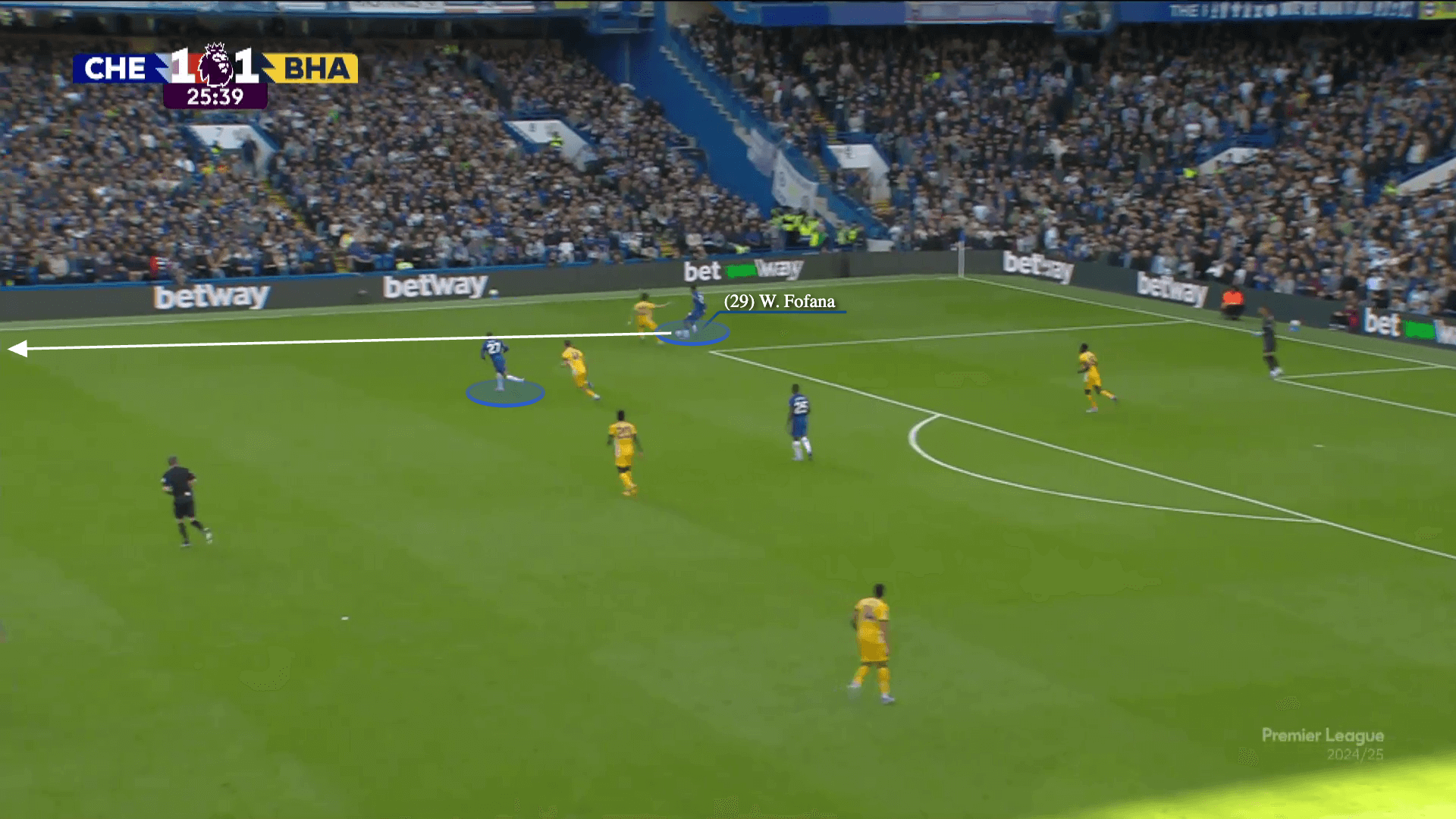

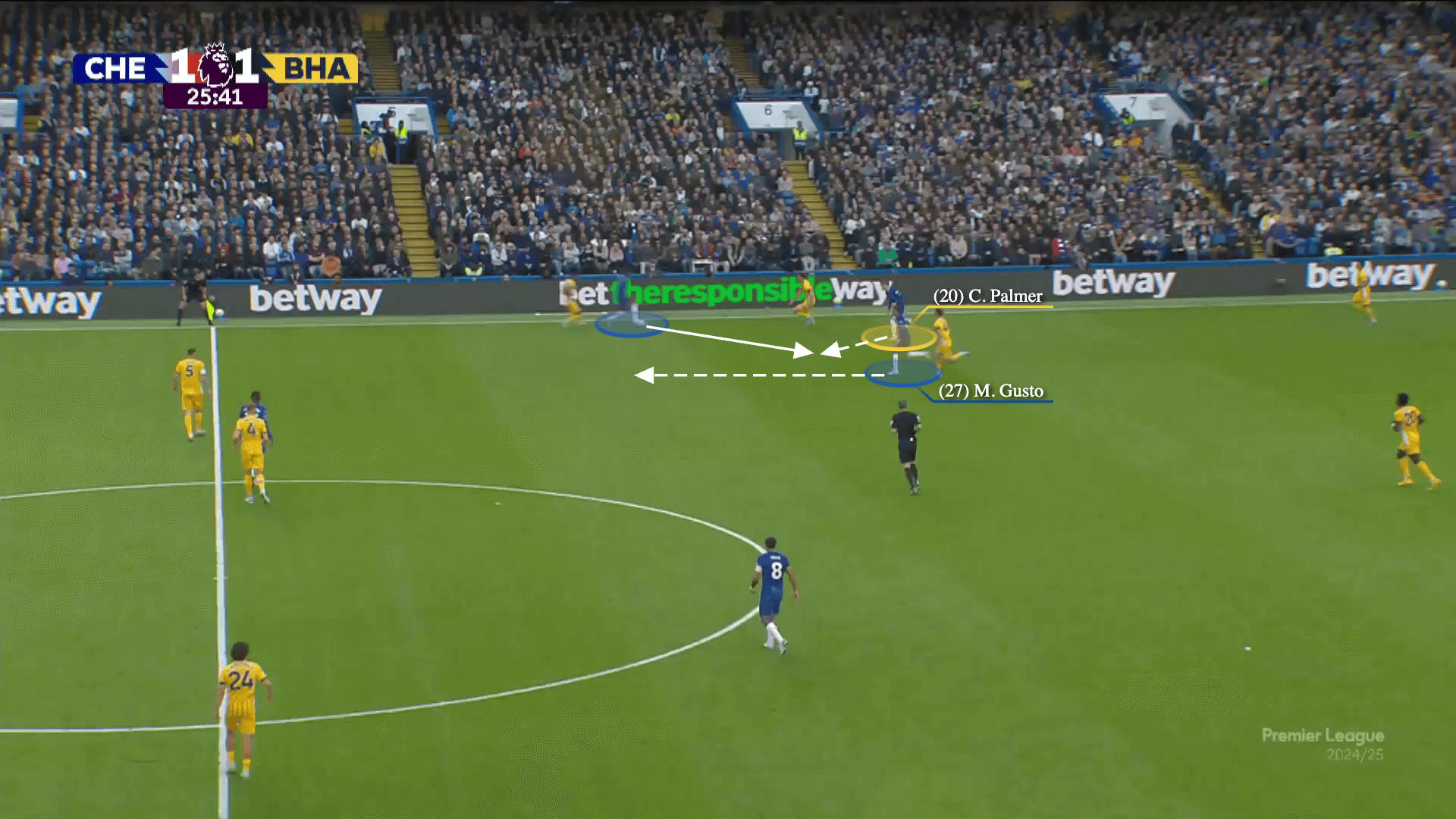

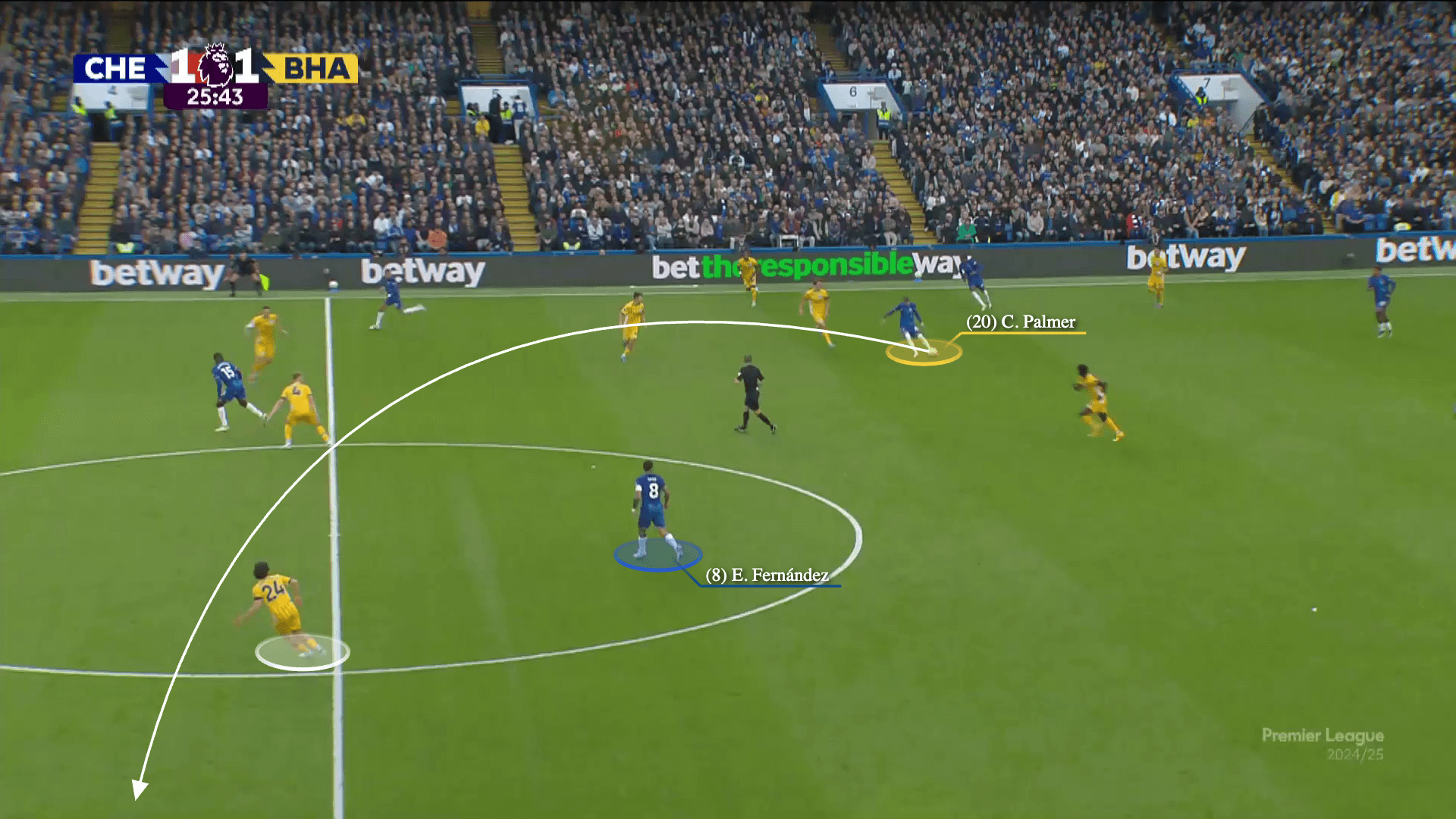

In another example, against Brighton & Hove Albion in September, Wesley Fofana tries to find a dropping Palmer near the right touchline…

… but the ball is closer to Madueke, who plays it back to the England midfielder with Gusto’s run clearing that zone for him.

Before Palmer switches the play to Sancho, it’s important to note the positioning of Enzo Fernandez as Chelsea’s left-sided No 10, and how that is forcing Brighton’s right-back, Ferdi Kadioglu, to position himself in between the midfielder and the left winger.

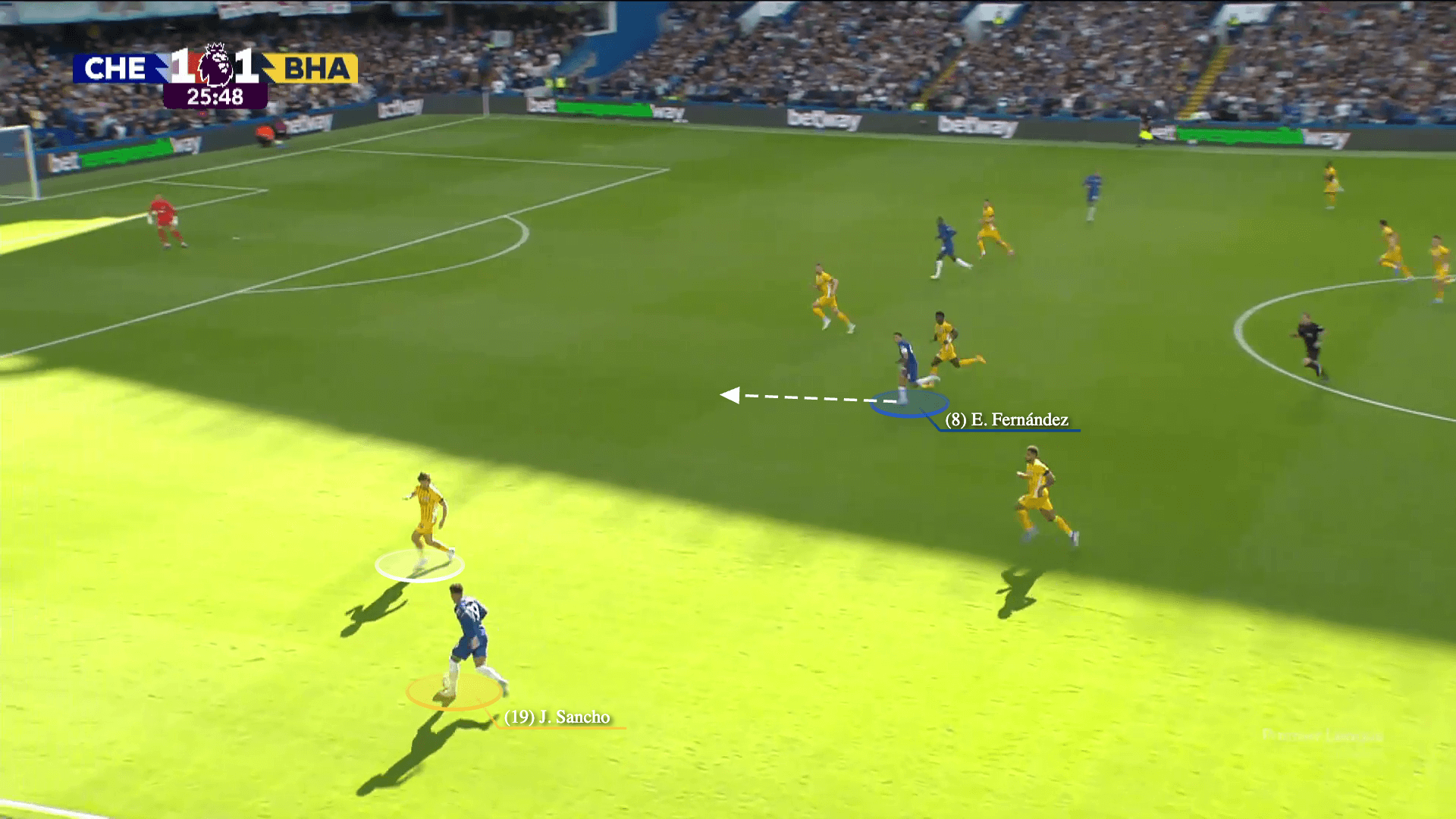

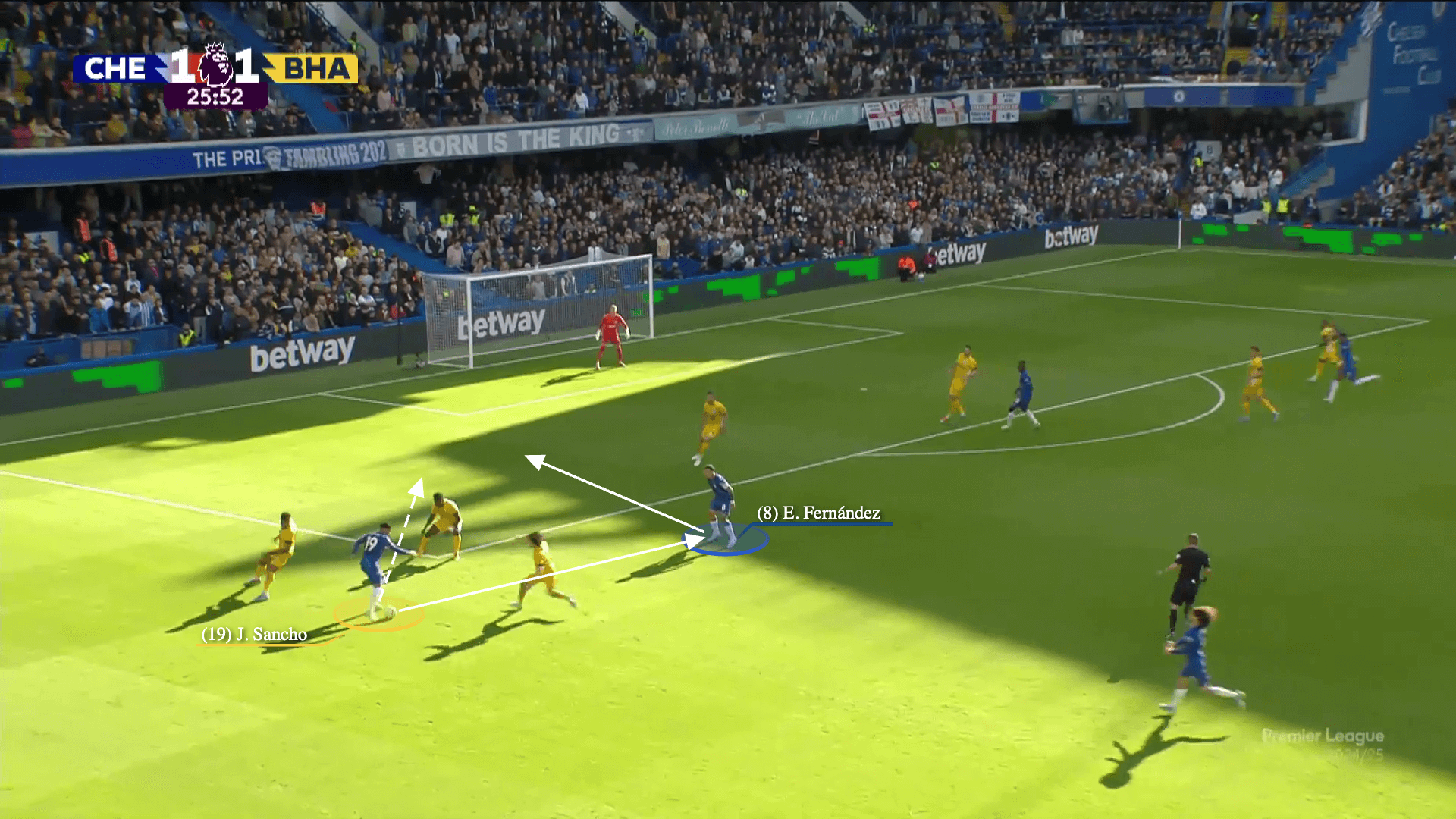

This allows Sancho to comfortably receive Palmer’s pass, before dribbling past Kadioglu in this one-versus-one situation…

… and combining with Fernandez to win the penalty from which Chelsea score their second goal.

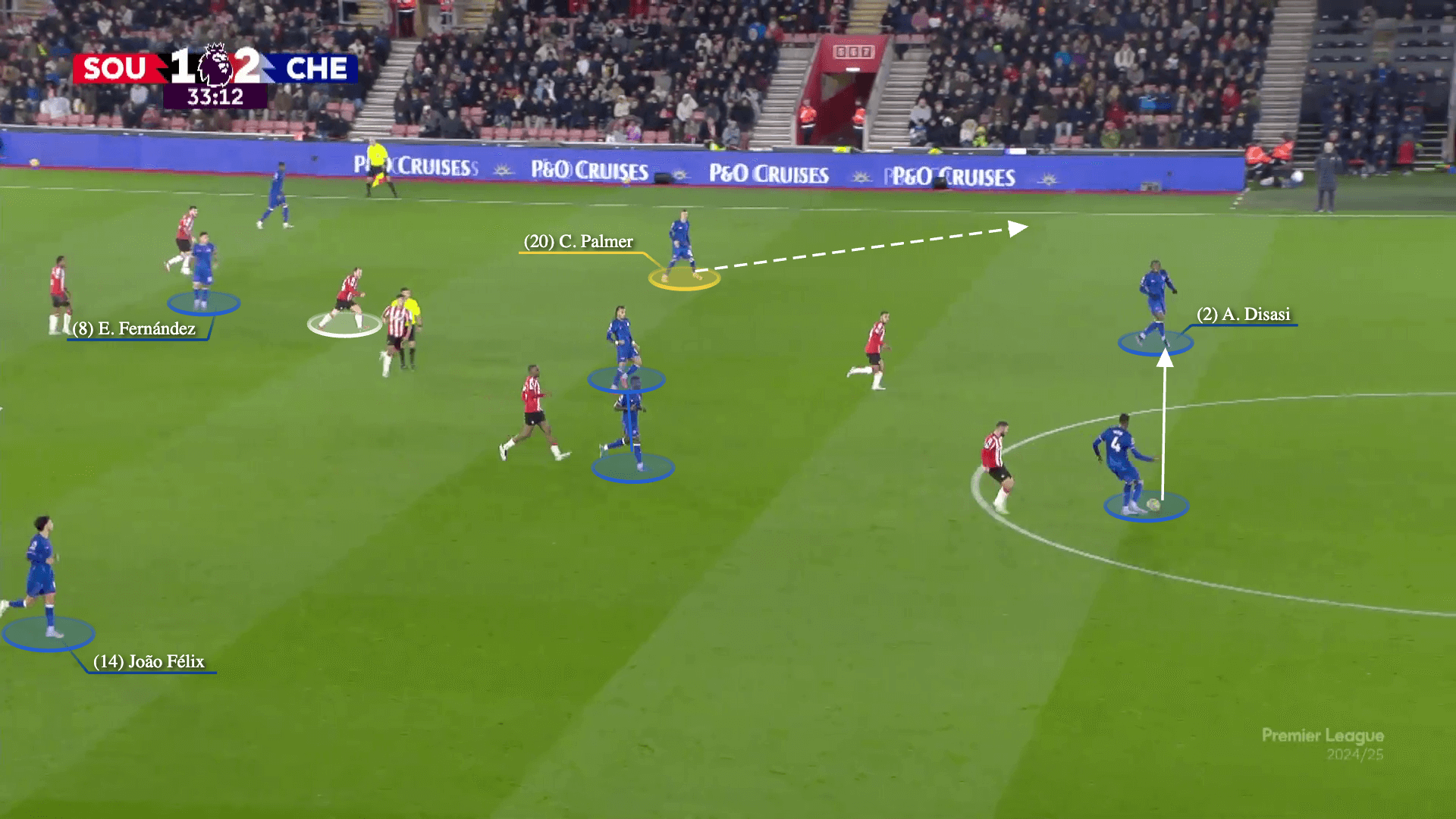

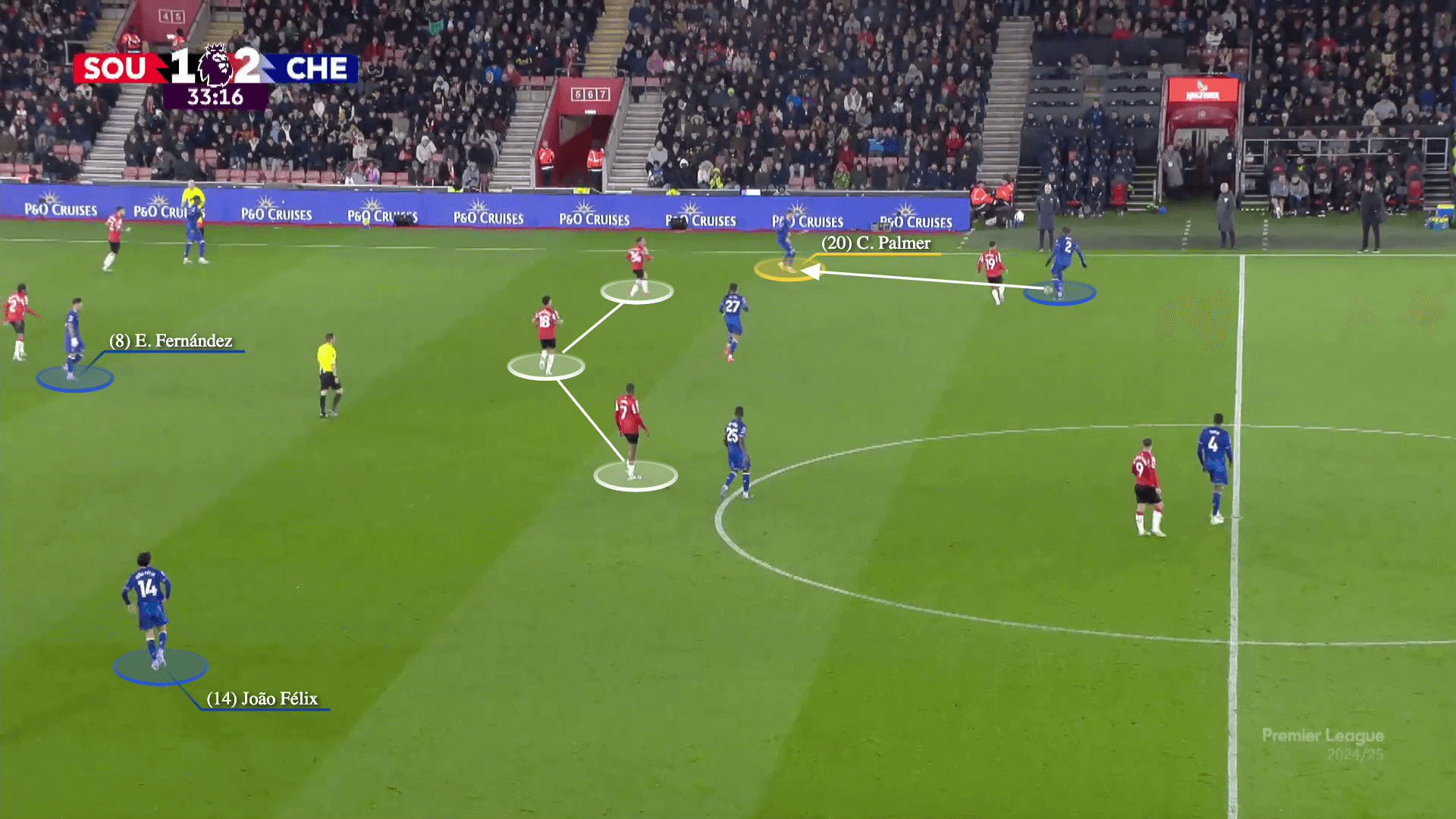

The off-ball movement of Chelsea’s No 10 is crucial to isolating the winger, who is attacking the same side of the pitch. In Chelsea’s 5-1 victory against Southampton this month, Palmer illustrated its importance.

Here, Chelsea are playing with three No 10s in front of Moises Caicedo and Gusto, with Cucurella providing the width down the left side.

Fernandez and Palmer briefly exchange positions, and the England midfielder does his customary move of dropping towards the touchline to offer a passing option.

Palmer’s movement attracts Ryan Fraser and shifts Southampton’s midfield towards the far side of the pitch. Axel Disasi then plays the ball to him…

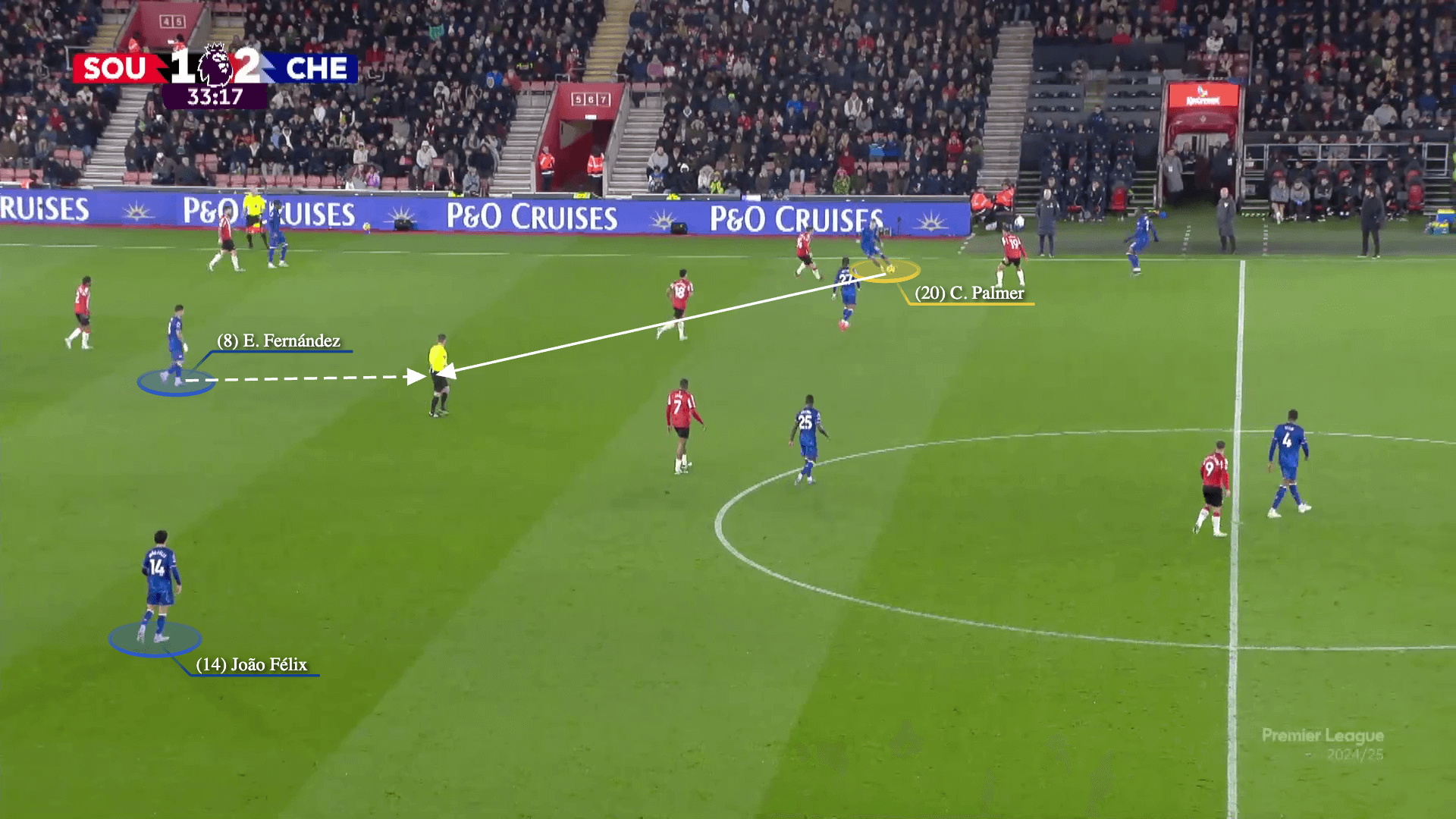

… and Palmer exquisitely finds Fernandez between the lines.

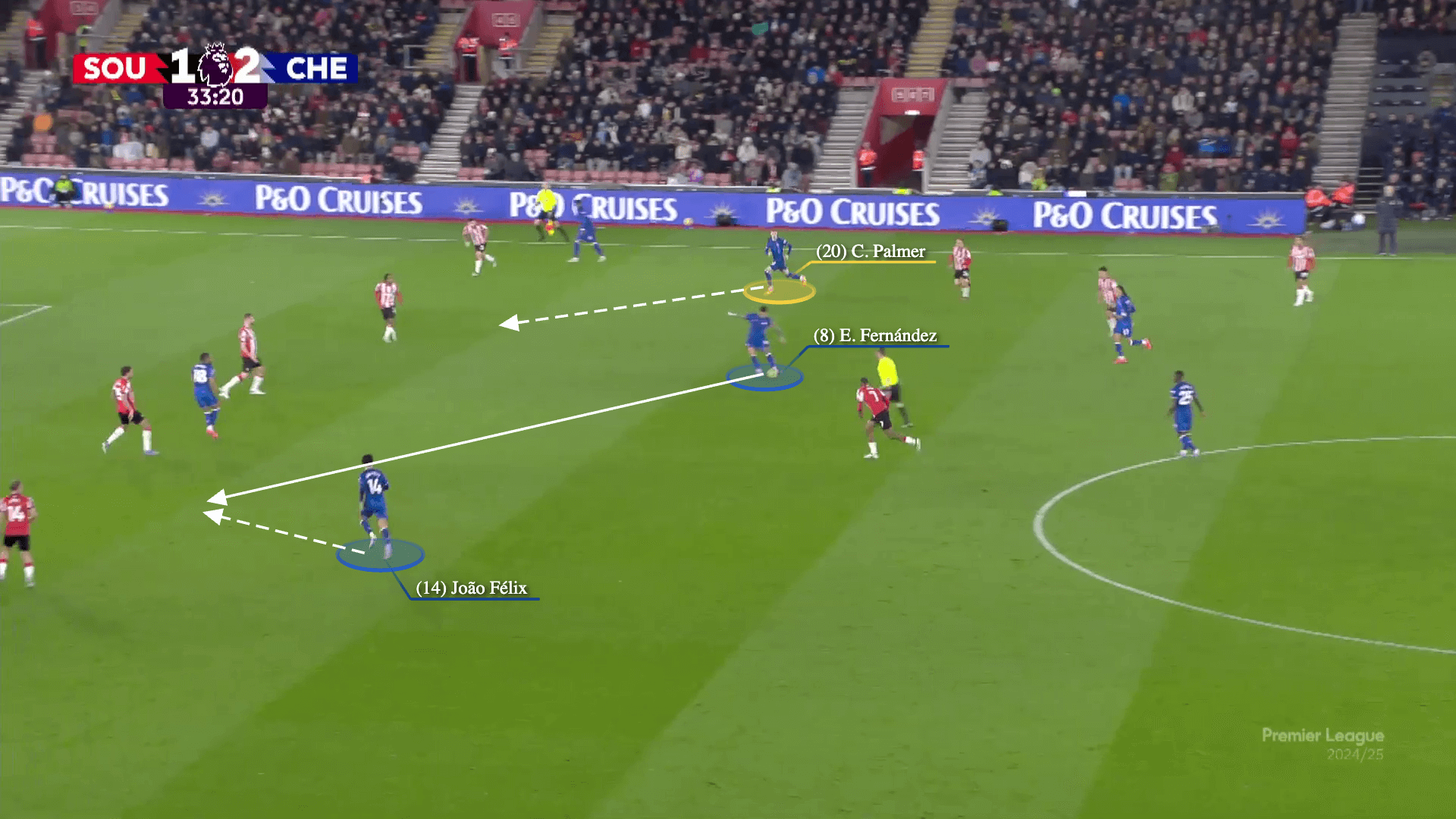

As Fernandez switches the play to the left side, where Joao Felix and Cucurella (out of shot) are creating an overload, Palmer is surging forward on the right and this comes in handy when the Portugal forward isn’t able to find Chelsea’s left-back.

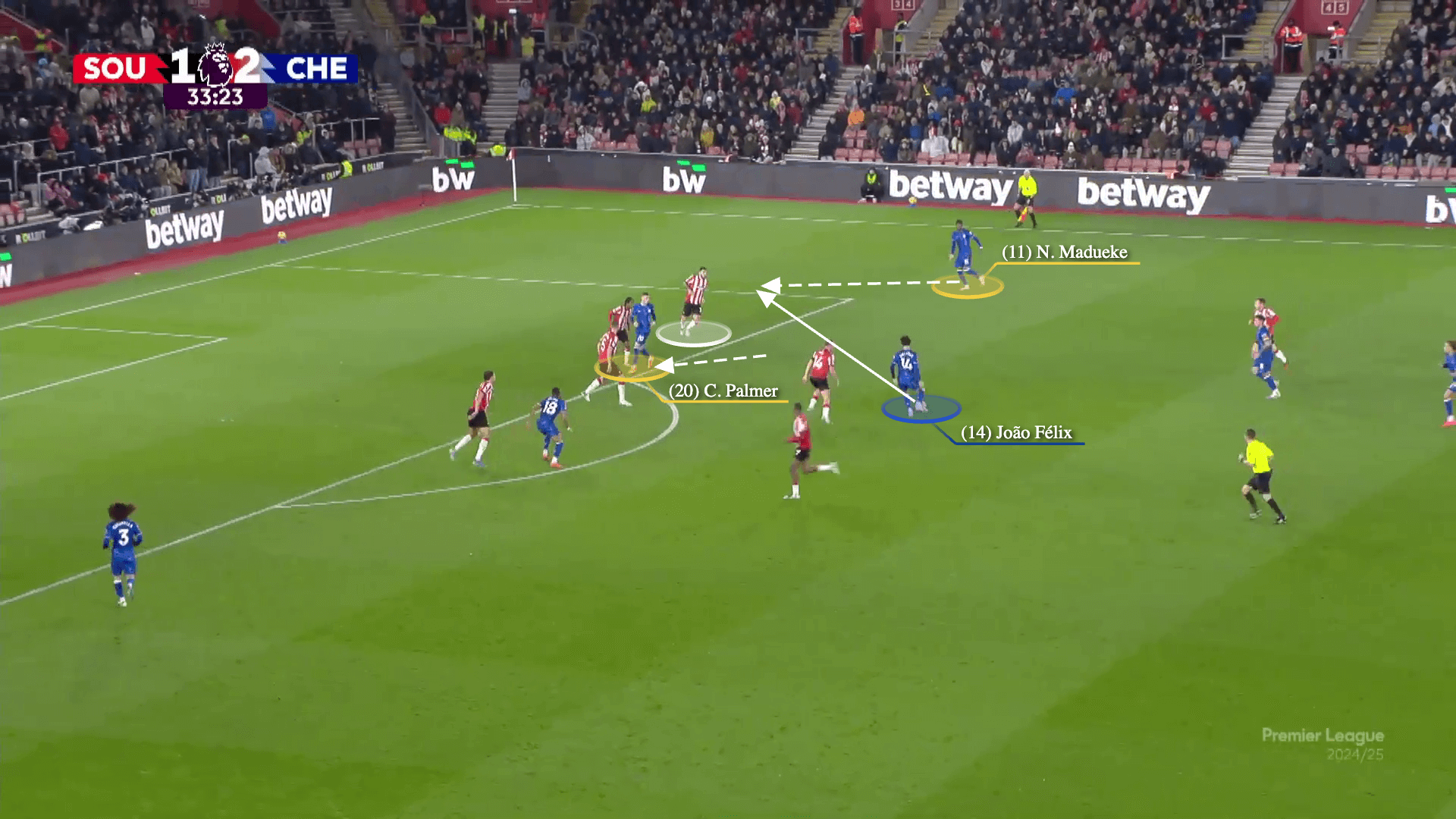

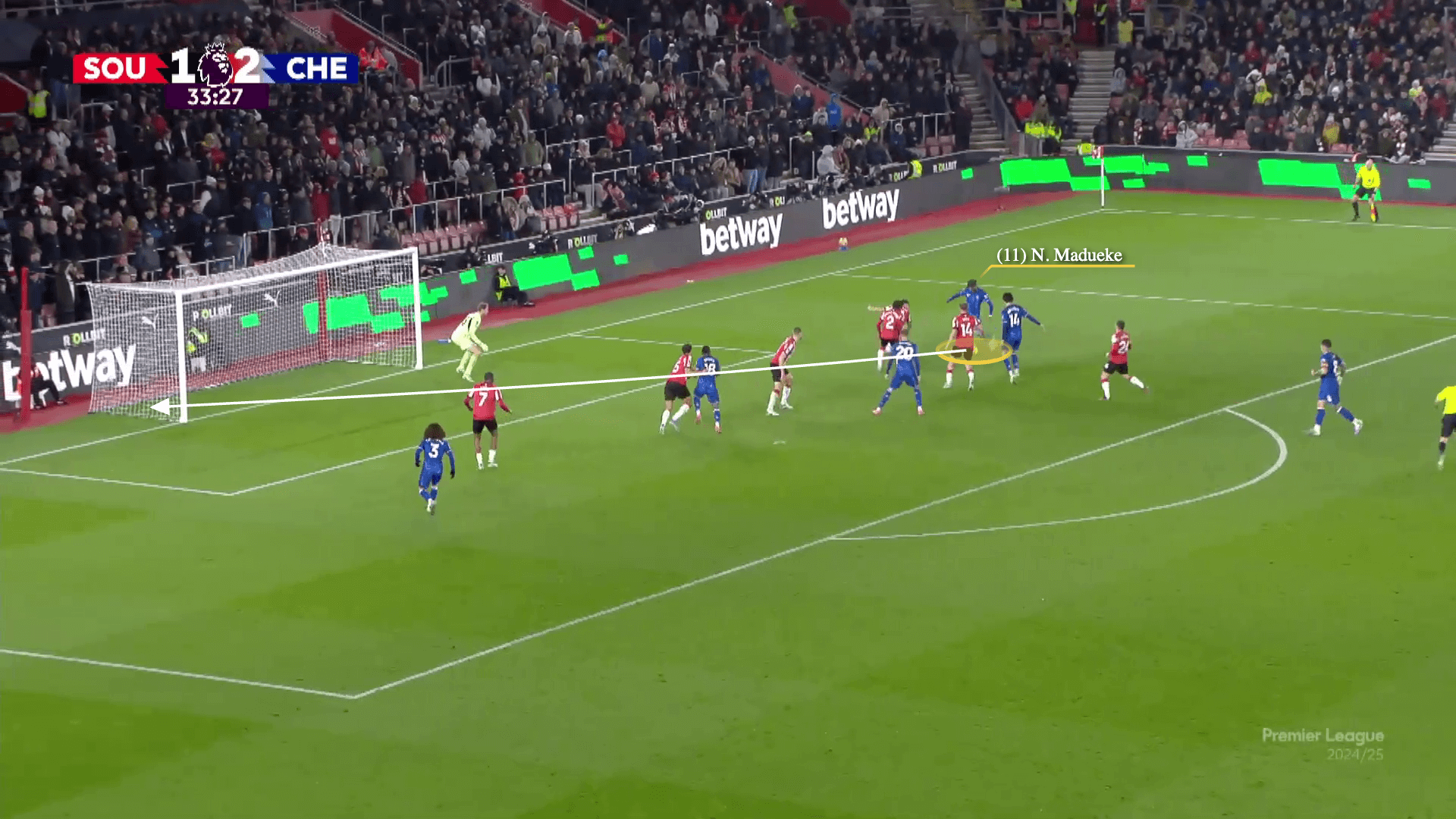

Felix goes to the other side and, by the time he plays the ball to Madueke, Palmer has moved forward and pins Southampton’s left centre-back, Kyle Walker-Peters, to put Chelsea’s winger in a one-versus-one situation.

Palmer’s movement helps Chelsea reach their goal of isolating Madueke against Southampton’s wing-back in a dangerous area, and the right winger finishes the job by curling the ball into the bottom corner.

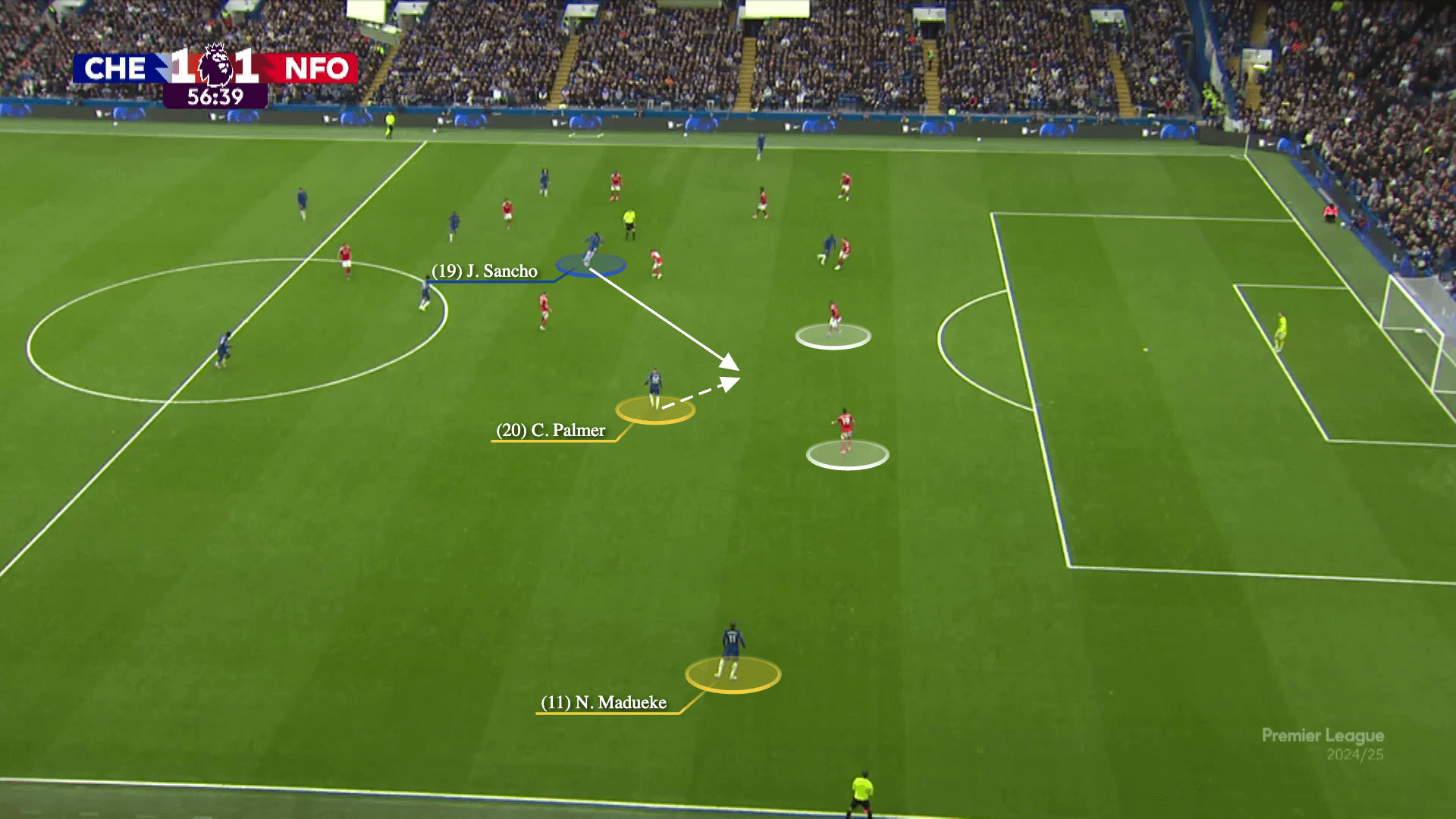

Madueke’s goal against Nottingham Forest in October is another example where the movement of the No 10 is vital.

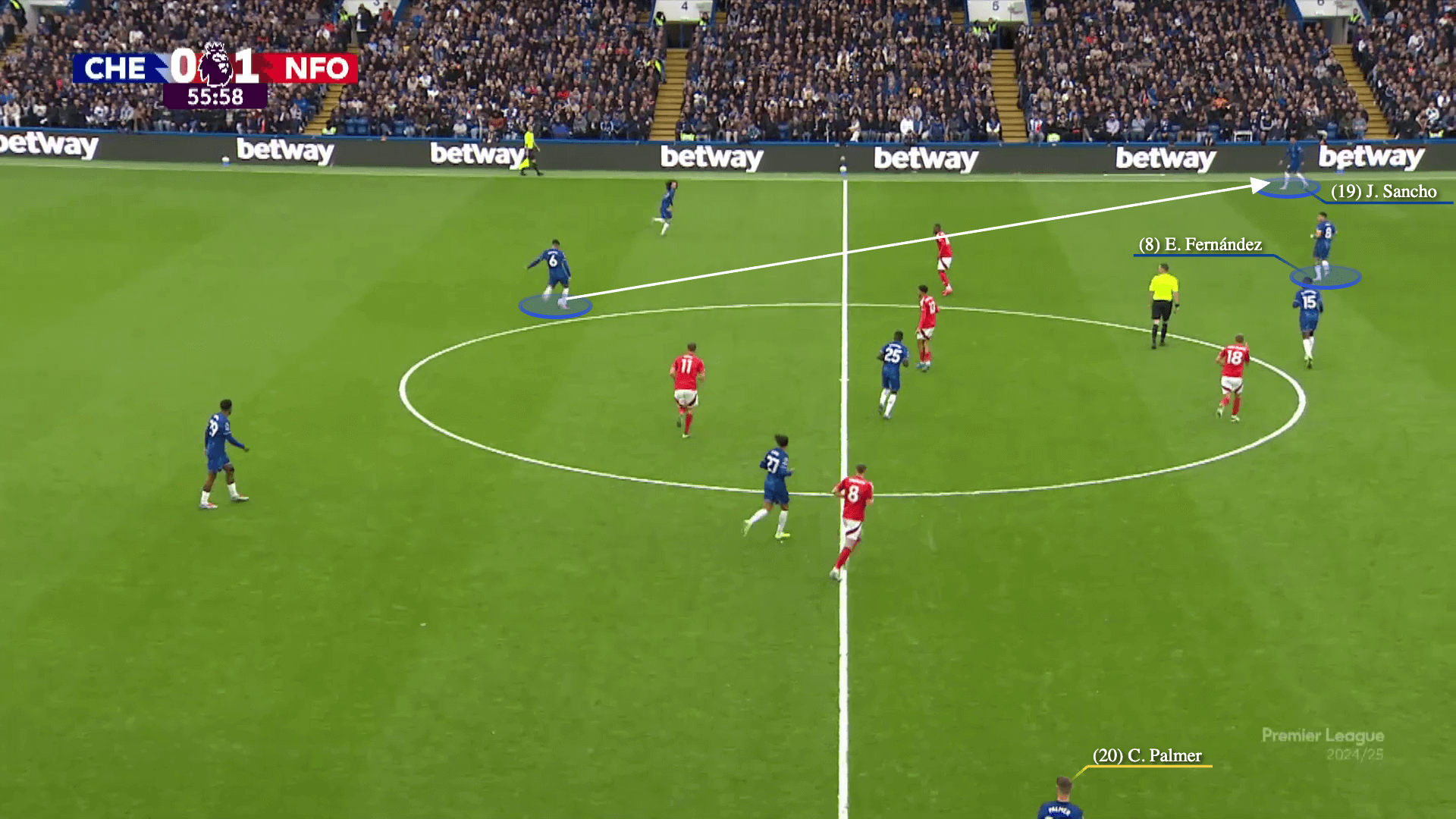

On this occasion, Chelsea play the ball directly to their left winger, Sancho…

… and Fernandez creates space for him to dribble inside the pitch by dragging Ryan Yates deeper.

Sancho then combines with Caicedo in midfield, with Forest’s right-back and central midfielder out of position. However, that’s not the biggest problem for Forest because Palmer is completely free on the other side of the pitch…

… and Sancho finds him between the lines.

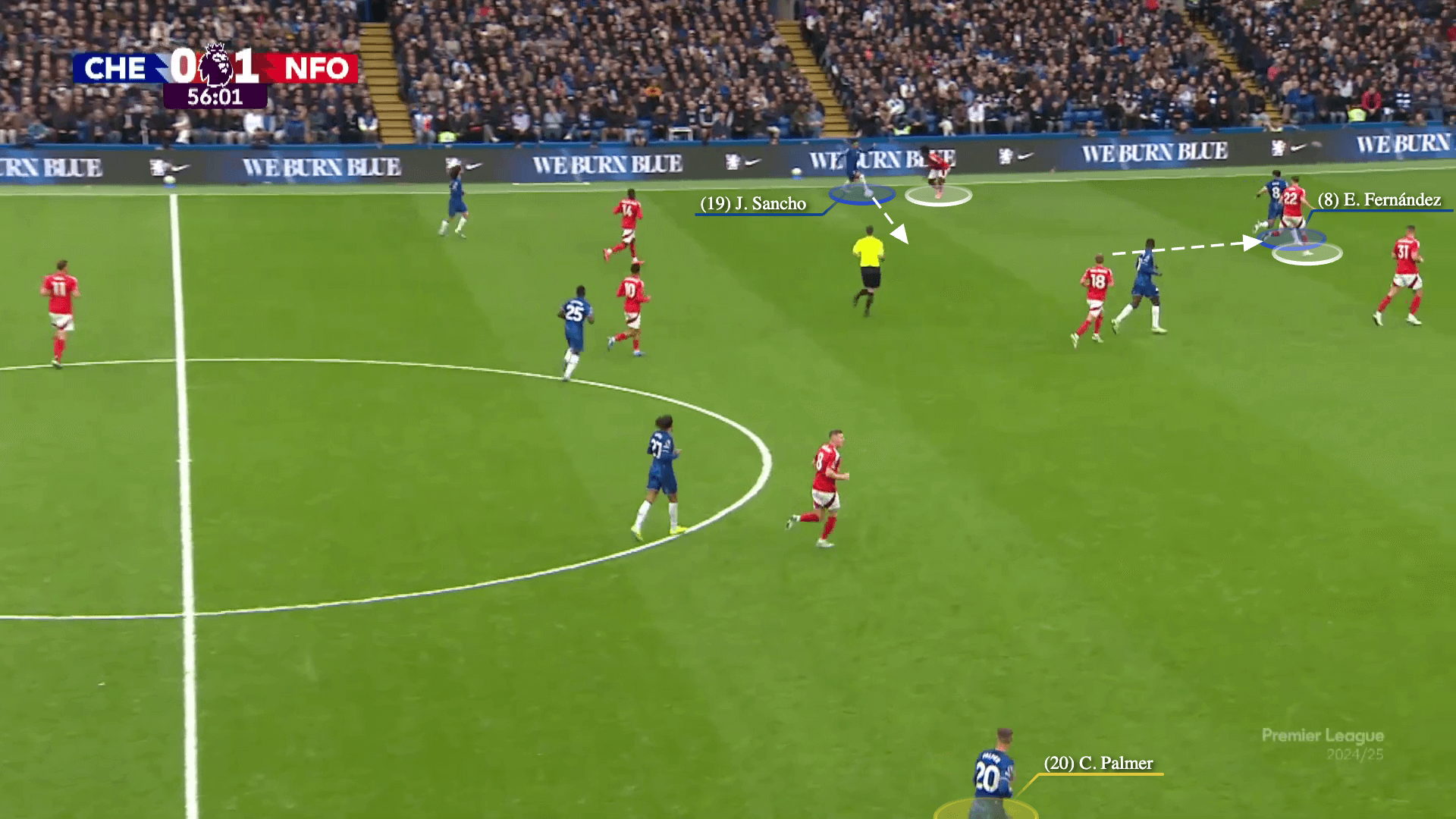

If you have been following Palmer throughout the previous images, you can see how slowly he moves into this space to maintain a distance between himself and Forest’s left centre-back, ensuring he arrives at the right moment.

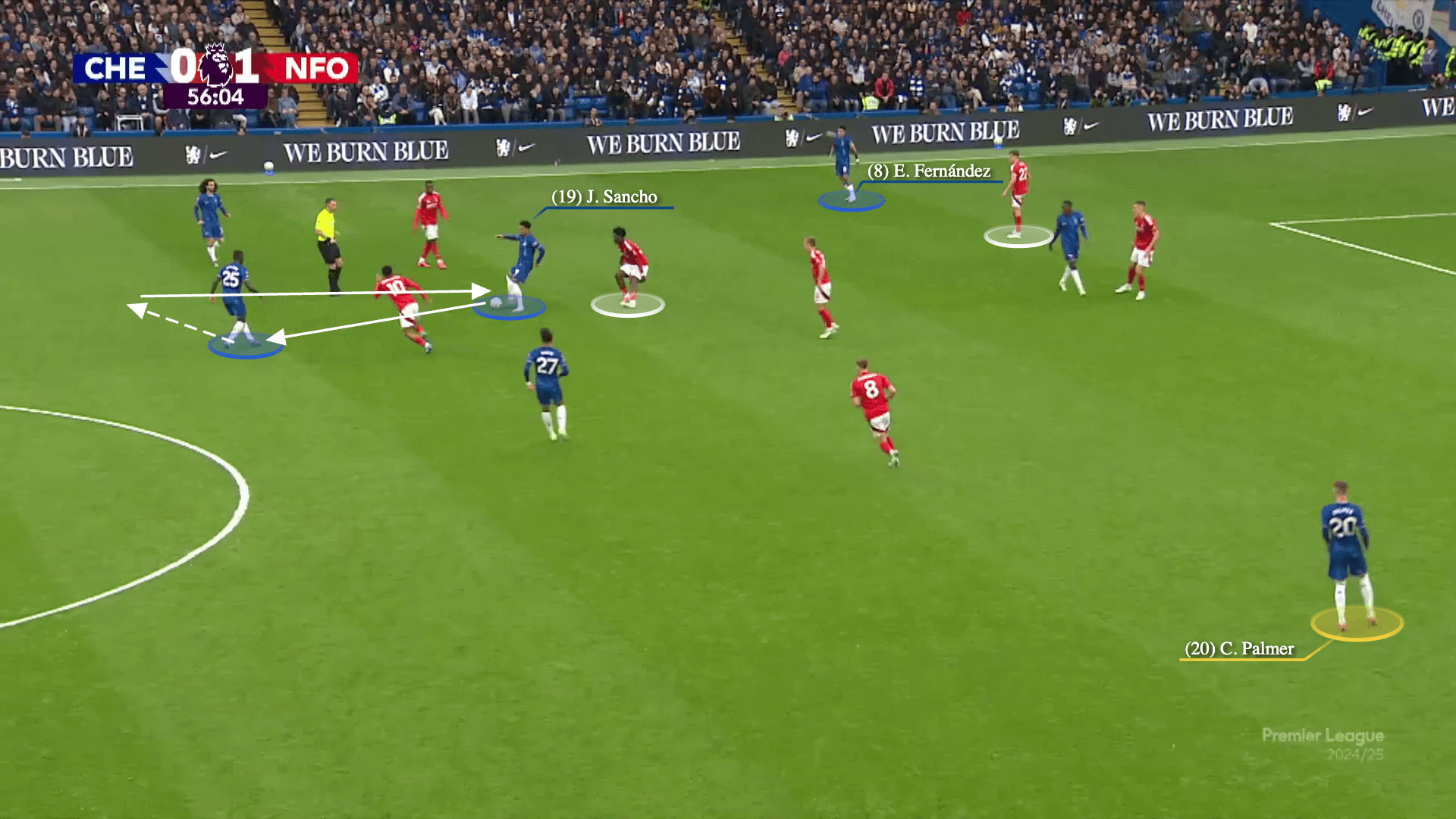

By doing that, Forest’s left centre-back has to move up when Palmer receives the ball, and the left-back, Alex Moreno, takes a couple of steps inside the pitch in case he needs to cover.

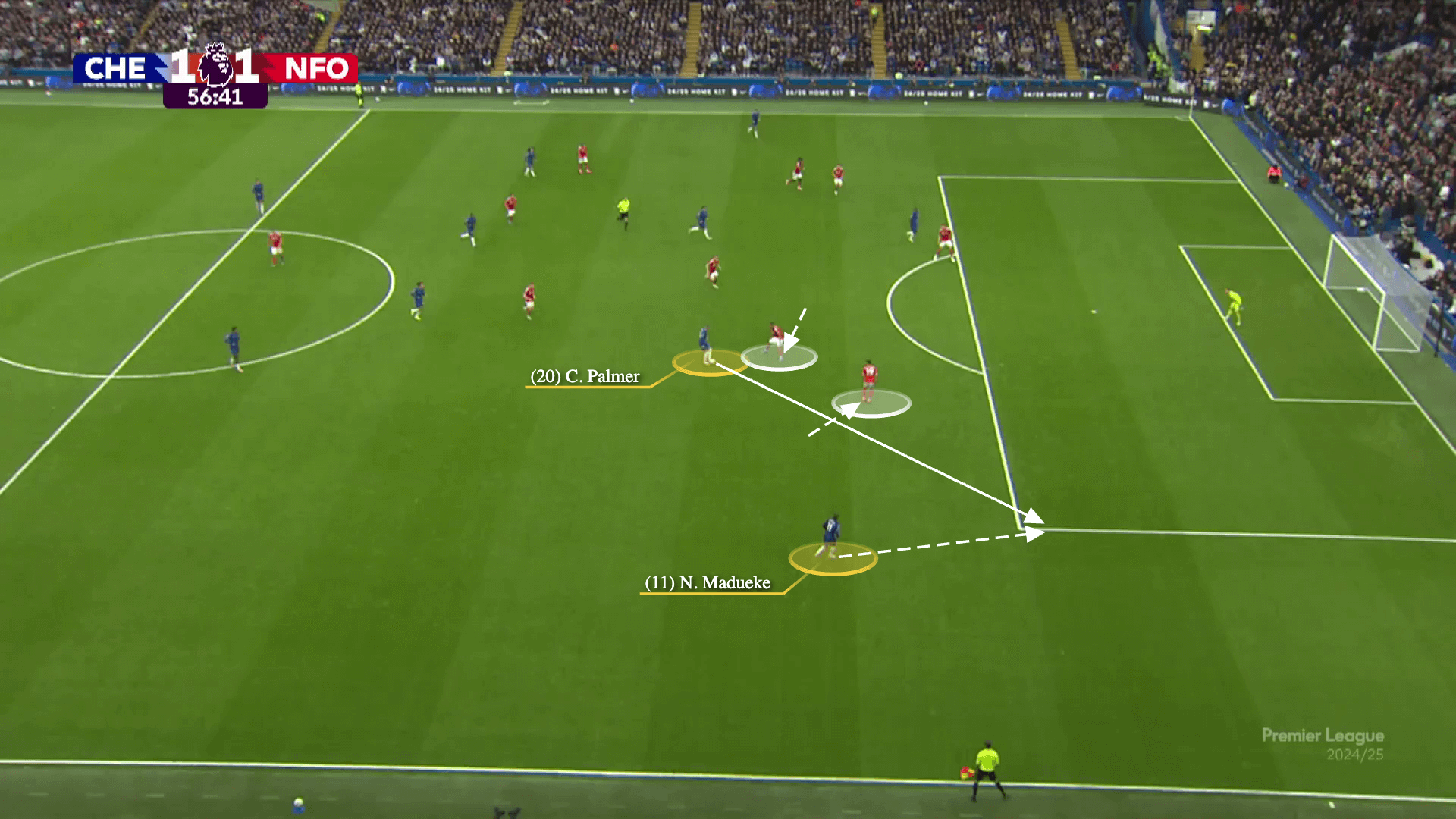

This distances Moreno from Madueke, and Palmer puts his winger in a threatening one-versus-one situation…

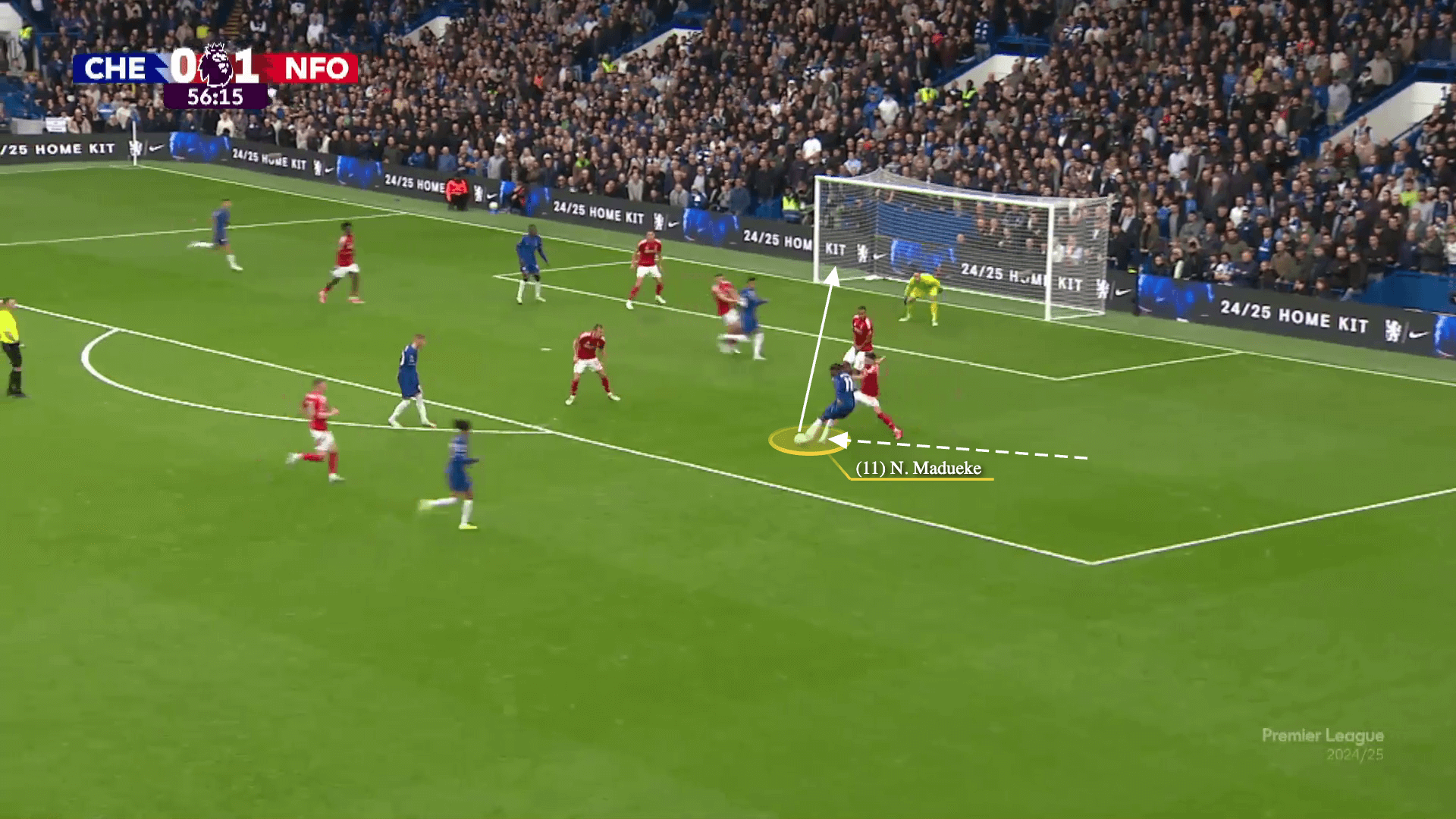

… before Madueke dribbles inside the pitch and strikes the ball into the far corner.

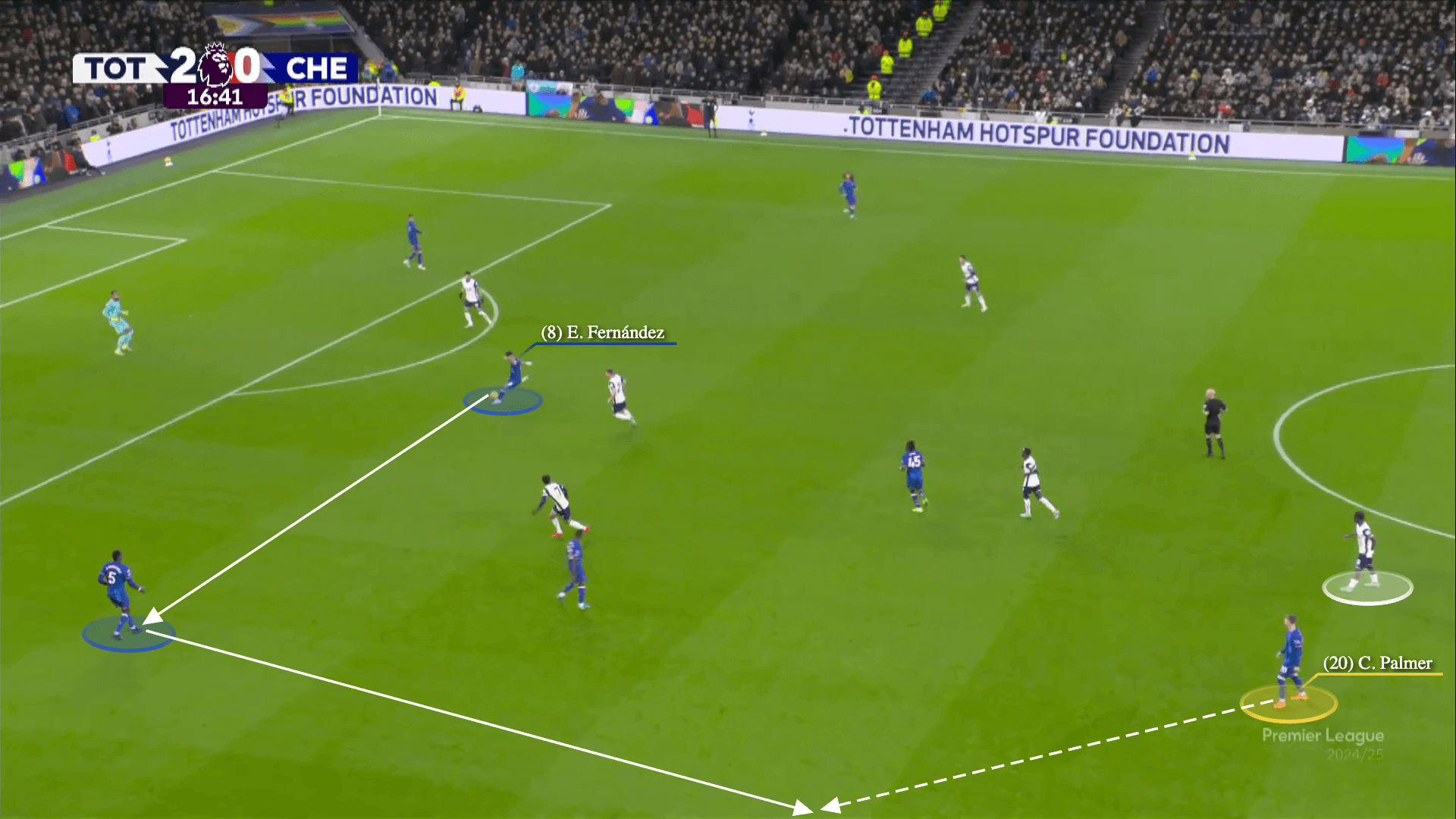

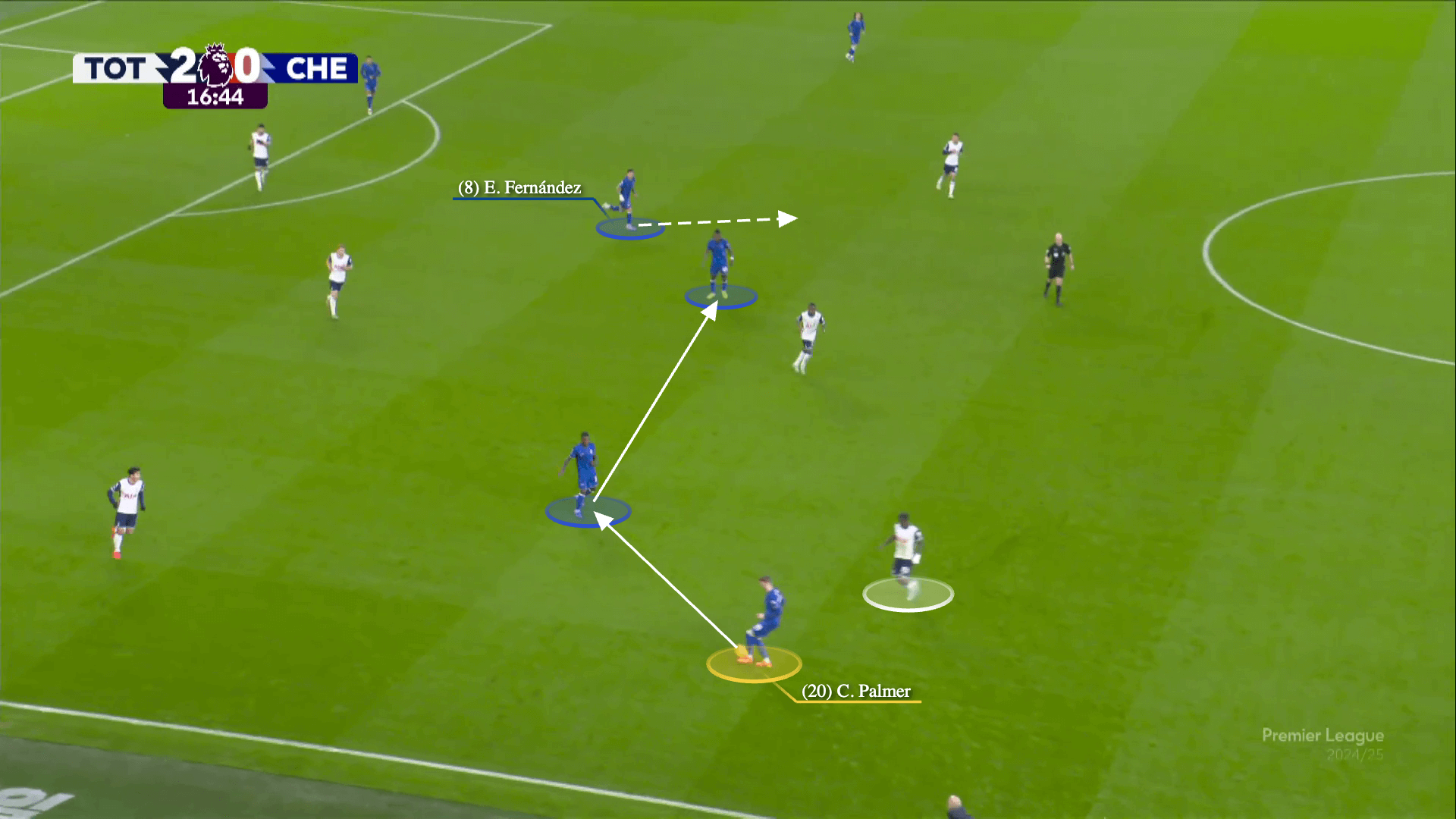

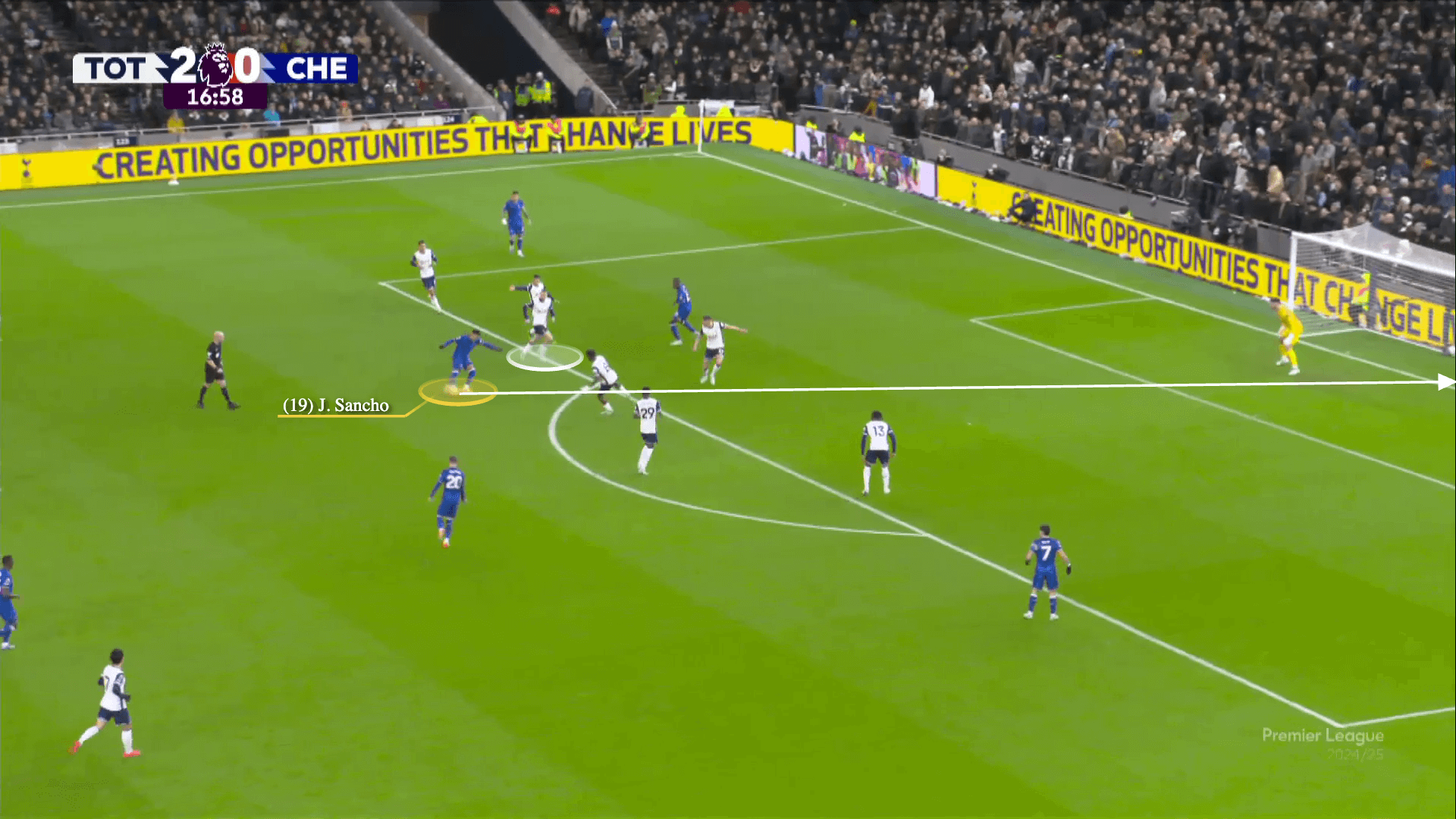

Chelsea’s first goal in their 4-3 victory away at Tottenham last Sunday encapsulates all the different parts of this tactic.

Fernandez drops from his left-sided No 10 role to help the build-up by playing the ball into Benoit Badiashile, who immediately finds Palmer near the touchline.

Palmer’s movement drags Yves Bissouma away from midfield, and the England midfielder quickly plays the ball to Caicedo as Chelsea switch the play to the other side of the pitch.

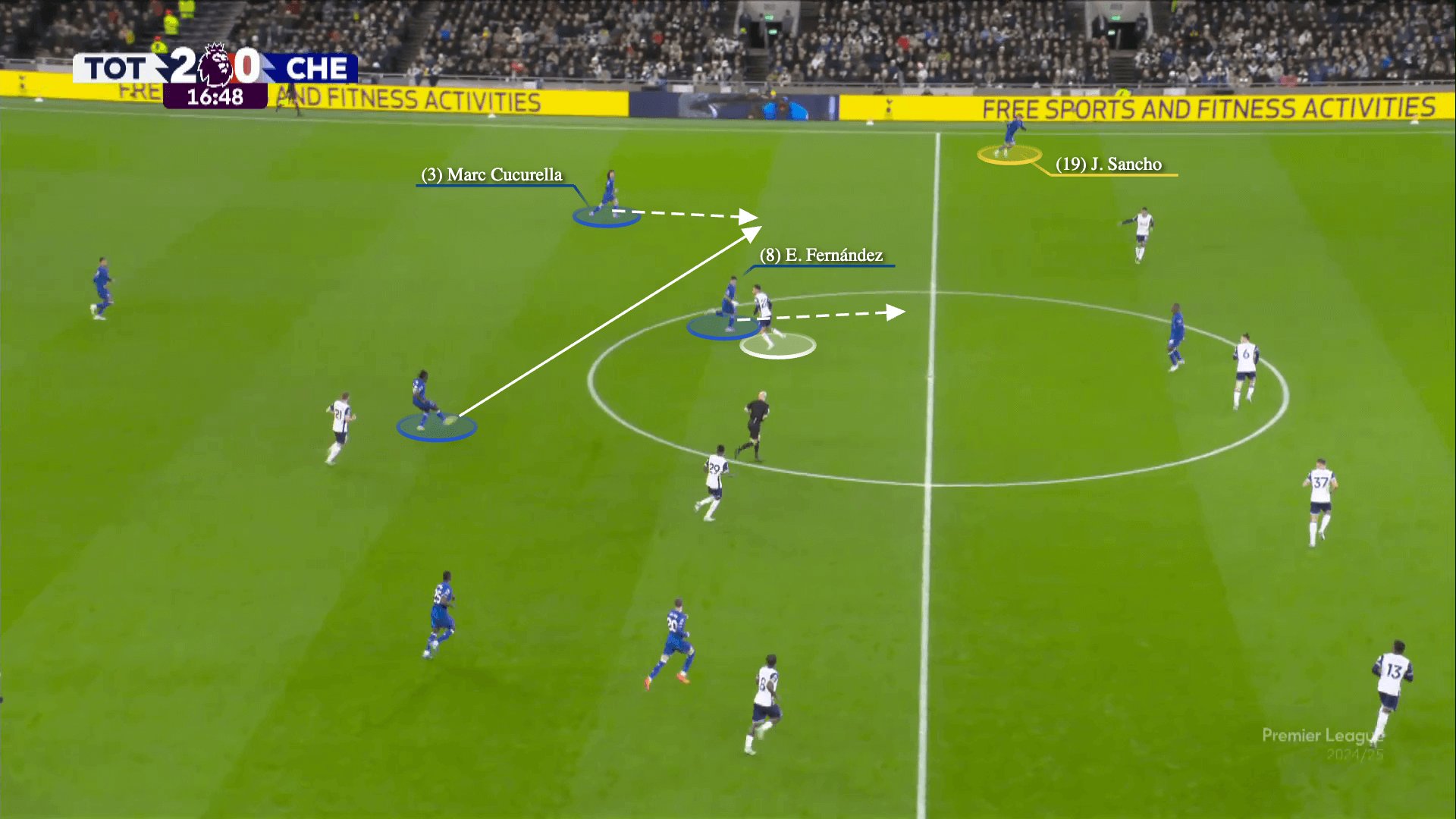

Meanwhile, Fernandez is moving forward to return to his position and Brennan Johnson ignores him because the winger’s task is to defend Cucurella, who Chelsea are switching the ball to.

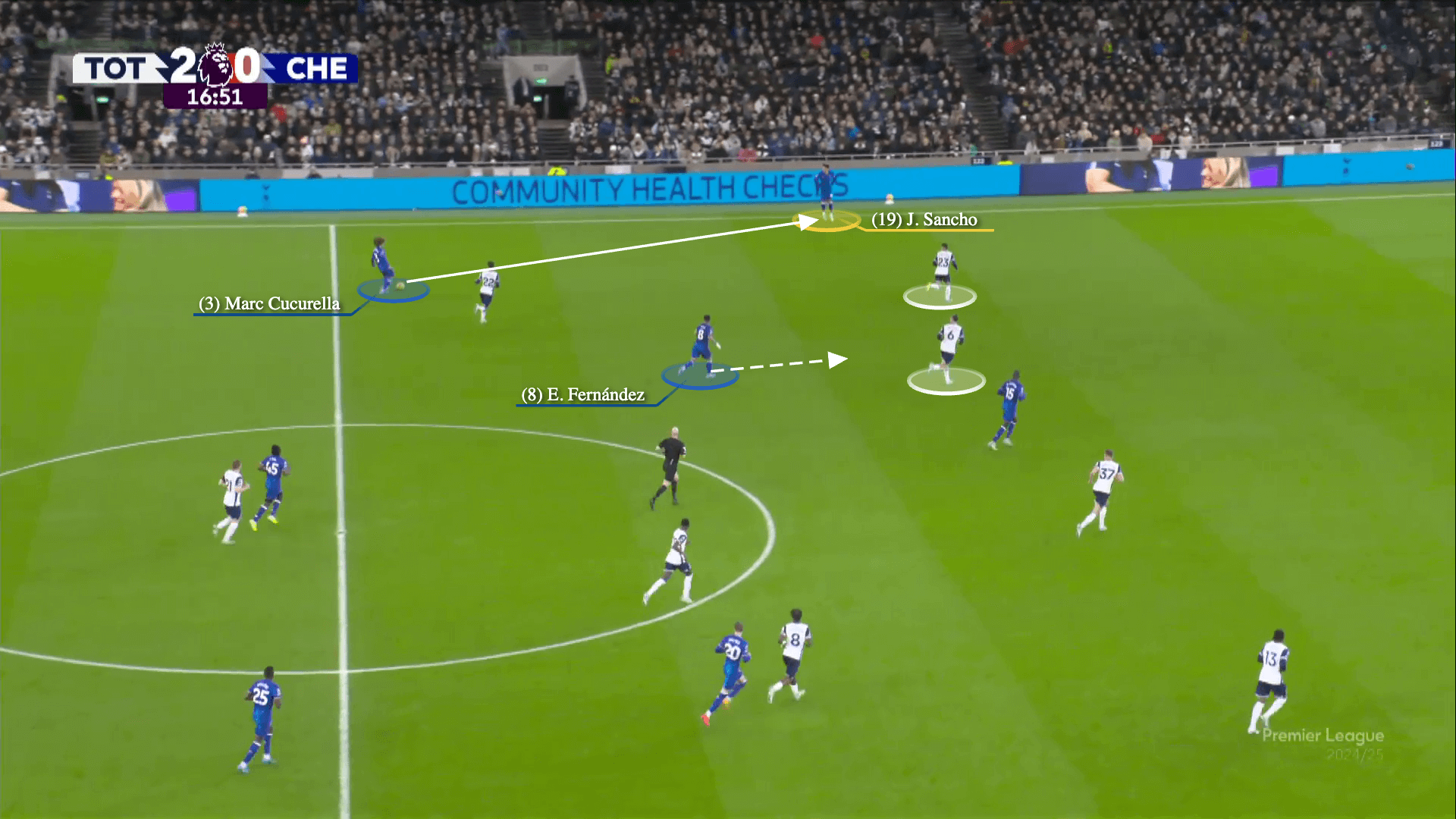

The consequence of Bissouma being moved out of position by Palmer and Johnson focusing on Cucurella is Radu Dragusin having to defend Fernandez, which in turn puts Sancho in a one-versus-one situation when the ball reaches him.

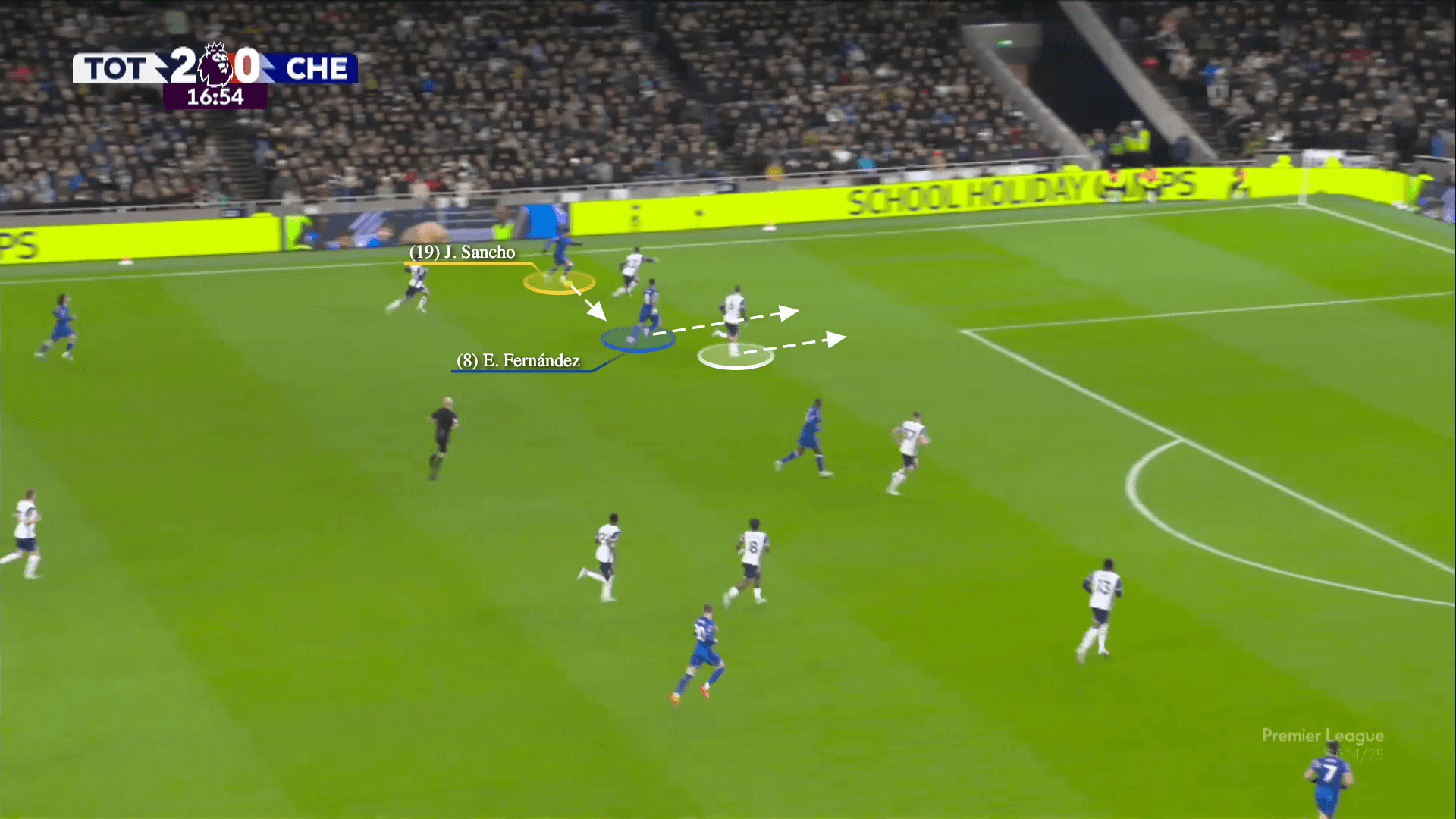

Fernandez then dashes forward to force Dragusin deeper and create space for Sancho, who dribbles inside the pitch…

… and drills the ball into the bottom corner to start Chelsea’s comeback.

The dribbling ability of Chelsea’s wingers will make them excel in one-versus-one situations, but the trick is knowing how to create these situations in the first place.

Maresca wants to isolate his wingers, and he is providing Chelsea with the method to achieve exactly that.

(Header photo: Darren Walsh/Chelsea FC via Getty Images)