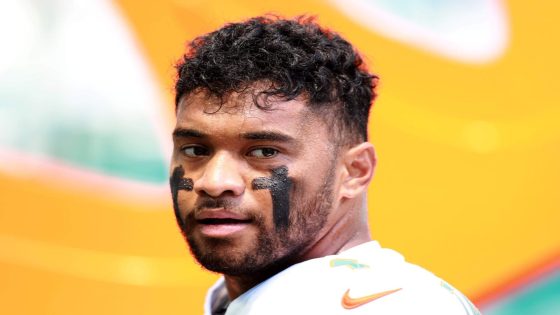

Miami Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa is expected to make his return to action Sunday against the Arizona Cardinals after missing four games due to a concussion he suffered in Week 2. It was Tagovailoa’s third diagnosed concussion in two years, which prompted league-wide discussion about whether he should continue playing football.

Provided he was medically cleared to play, that decision was always going to rest with Tagovailoa. He considered retiring after missing four games due to two separate head injuries in 2022 but said it wasn’t a consideration this time around. He chose to keep playing after discussing the situation with his wife, Annah.

“No one’s … advice had affected anything that I thought in terms of returning,” Tagovailoa said Monday. “(I) had some conversations with my wife, but that was it.

“I love this game,” he continued, “and I love it to the death of me.”

Asked if he would wear a Guardian Cap — the padded shells some players wear over their helmets to lessen the impact of collisions on the brain — Tagovailoa said he would not, calling it a “personal choice.” He does, however, wear a VICIS-brand helmet deemed the “safest” among standard helmet options for quarterbacks.

Like other players diagnosed with concussions, Tagovailoa had to go through the league’s return-to-participation program.

The first step for players is becoming asymptomatic. Before the start of training camp, every NFL player is evaluated by his team’s neuropsychologist to establish a neurological baseline. Players have to return to that baseline to be deemed asymptomatic.

Tagovailoa said he felt symptom-free the day after suffering his latest concussion, but the Dolphins still placed him on injured reserve. There’s no required timeline to clear the NFL’s concussion protocol, but being placed on IR meant he would have to miss at least four games.

“Given what the doctors have told me that having a substantial amount of time to rest and recover would have been good for me, I think they did what was best in terms of protecting myself, you know, from myself,” Tagovailoa said.

Once the Dolphins’ neuropsychologist deemed Tagovailoa to be asymptomatic, the quarterback entered a five-phase exercise program. As we wrote following his Week 2 injury, the protocol consists of gradually increasing activity, and the team is told to look for any recurrence of symptoms during each phase.

• Phase 1, symptom-limited activity: The player is prescribed rest and is told to limit or avoid activities that increase or aggravate symptoms. Under athletic training staff supervision, limited stretching and balance training can be introduced, progressing to light aerobic exercise. If tolerated, the player can attend meetings and film study.

• Phase 2, aerobic exercise: Under the supervision of team staff, players can begin graduated cardiovascular exercise, such as on a stationary bike or treadmill. The player may also engage in stretching and balance training.

• Phase 3, football-specific exercise: The player continues supervised cardiovascular exercises and may mimic sport-specific activities and supervised strength training.

• Phase 4, non-contact training drills: The player can continue cardiovascular, strength and balance training, team-based sports-specific exercise and participate in non-contact football activities.

To proceed to Phase 5, Tagovailoa had to be examined and cleared by an independent neurological expert. That doctor, who doesn’t work for the NFL or the Dolphins, had to determine Tagovailoa was fully recovered. Although the NFL’s concussion protocol doesn’t change based on how many concussions a player has suffered, that independent expert takes the player’s complete medical history into account.

“The tests that that doctor performs — and then the steps that the player has to clear to even get to that point — are going to be the same regardless of whether he’s had one or two or three concussions,” Jeff Miller, the NFL executive vice president overseeing player health and safety, said earlier this month. “That doctor’s going to consider whatever steps he or she needs to consider to make sure that they’ve reached a conclusion they’re comfortable with as a clinical provider of concussion care.”

• Phase 5, full football activity/clearance: The player is finally cleared by the team doctor for full football activity involving contact. Tagovailoa received that full clearance on Wednesday.

“Every situation and every concussion is unique,” Dr. Allen Sills, the NFL’s chief medical officer, said earlier this month. “And so, we don’t put a time stamp on those processes because they will differ depending on the severity of the injury. … This return-to-play process is meant to be conservative. It’s meant to be rigorous. … Ultimately, the final decision of return to play is made by the player.”

The NFL believes it has made progress with how it handles concussions by enhancing its concussion protocol, making rule changes and improving equipment. That said, the number of concussions suffered in the league has increased every year since 2020.

In response, the NFL introduced 12 new helmet models this season, broadened its mandate on the use of Guardian Caps in practices, allowed players to wear Guardian Caps in games and altered the kickoff rules largely in the name of player health and safety. During the preseason, the number of concussions suffered in practices and games dropped to 44, the lowest figure since tracking began in 2015. But it remains to be seen whether that will carry over to the regular season.

Even if it does, a blind spot that remains for the NFL is the full scope of the short- and long-term risks associated with players who suffer multiple concussions. A 2022 report demonstrated a causal link between repetitive head impacts and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), but the league can’t predict the likelihood that players who previously suffered concussions will suffer more of them.

“We, unfortunately, do not have a detailed formula that can predict future risk of injury,” Sills said. “It’s not like we can put in your number of concussions and how long between them and your age and some unusual constant and … come up with a risk. It just doesn’t work that way. … We try as medical professionals to provide our best guess, but that’s really what it is — a guess at what someone’s future risk of concussion is.

“In my own practice,” Sills continued, “I’ll see patients who have had maybe two concussions in a 12-month period and then won’t have another concussion for another eight or 10 years. And then, other times, you see people that seem to be having them more frequently. So, there’s got to be something about genetic susceptibility and individual physiology, but we just aren’t at the point of our medical understanding to really be able to quantify that to a degree that lets us be super prescriptive about that.”

The doctors tasked with clearing players from concussion protocol are taught to take the totality of the patient’s experience into account. That includes the total number of concussions, the interval between concussions, the duration of symptoms after each concussion and more. If a player is cleared by both the independent and team doctors, it’s up to him whether he continues to play.

Tagovailoa isn’t the first player with a lengthy history of concussions to keep playing, and he likely won’t be the last. And, even if the league or players association wanted to step in and stop him from playing, there is no option permitting them to do so.

“There’s a degree of medical autonomy,” Sills said. “It’s really not that different from day-to-day medical practice. I’m a surgeon. If I walk in and talk to a patient in the room and I recommend that they have an operation for a variety of reasons and I outline those reasons and I give them the risks and the benefits of that surgery, then ultimately, it’s the patient’s decision whether they want to have that surgery done or not.

“Patient autonomy in medical decision-making really matters. That’s what we have to recognize goes on with our concussion protocol as well. When patients make decisions about their careers, it has to reflect that autonomy that’s generated from discussions with medical experts giving them the best medical advice.”

For Tagovailoa, the risk was one he was comfortable taking.

“How much risk do we take when we get up in the morning to drive to work?” Tagovailoa said. “There’s risk in any and everything. And I’m willing to play the odds.”

(Top photo: Carmen Mandato / Getty Images)