What’s the right moment to hitch your hopes to an up-and-coming tennis player?

People were having visions of Carlos Alcaraz’s future when he was 10, the age at which Babolat and the other big racket companies sometimes start handing out equipment and swag. At France’s Les Petit As, the premier tournament for juniors 14-and-under, any prospects racking up games, sets and matches will already have an agent in their parents’ ear, if not a signed contract.

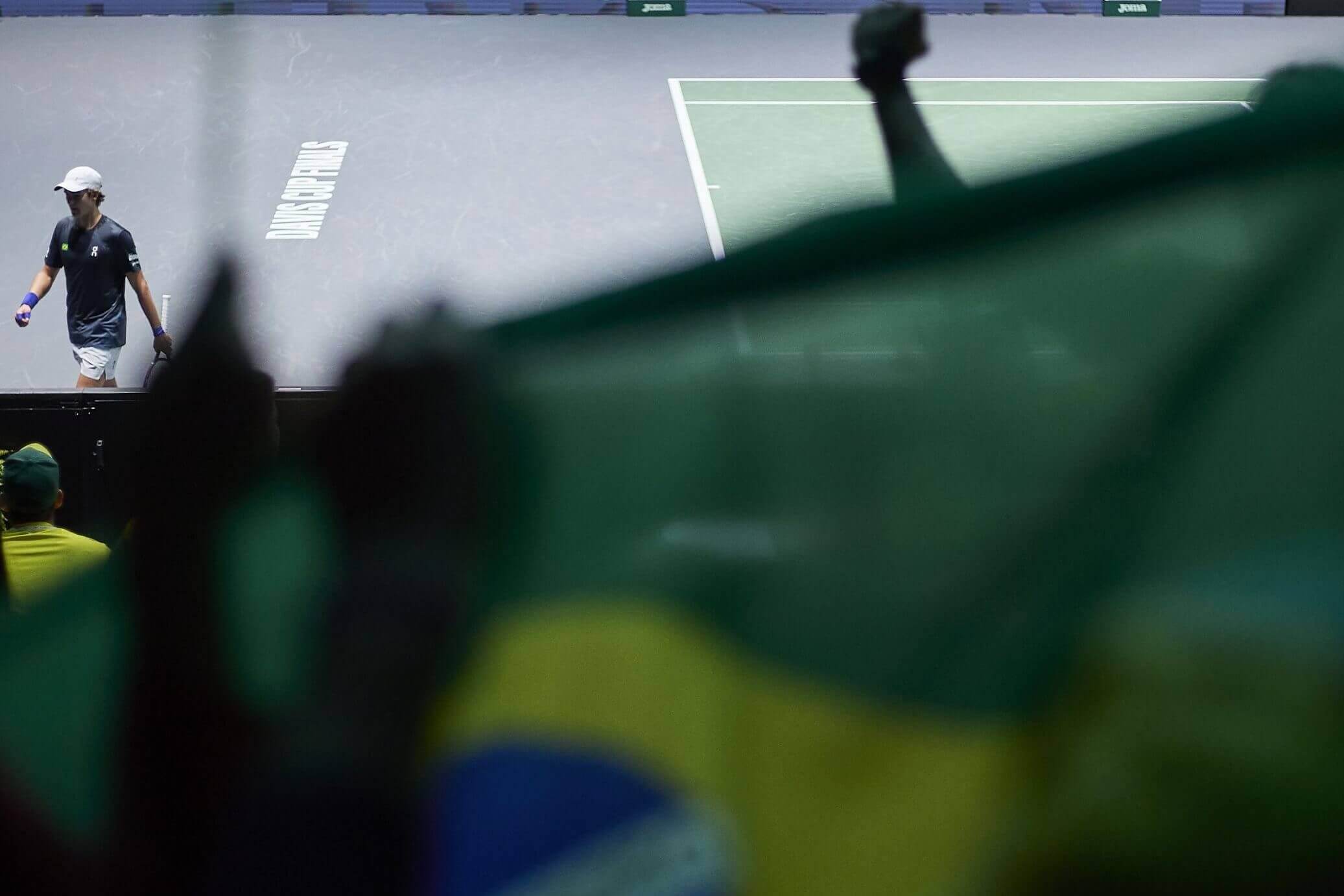

By those measures, having faith in Joao Fonseca, the easy-going Brazilian teenager with the wavy light hair who can already hit serves at 140mph (225kmh), seems like a pretty conservative bet.

Some more numbers. At 18, he’s the youngest player to make the field for the ATP Next Gen Finals in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, a competition for the top-ranked men’s players who are 20 or younger. And at 6-foot-1 (185cm), Fonseca is in the Goldilocks zone — not too tall, not too short — of players who have won most of the Grand Slams the past decade.

Fonseca grew up worshipping Roger Federer, which is part of the reason his lead sponsor is On, the Swiss sports manufacturer that Federer has a significant stake in. On signed Fonseca, who hails from Rio de Janeiro, two years ago when he was just 16.

“They said it was going to be me, Iga (Swiatek) and Ben Shelton,” Fonseca recalled during an interview last month. “Of course I said yes.”

Perhaps Fonseca’s business acumen is as precocious as his tennis talent. On’s stock price was $17.36 two years ago. It’s around $55 now. His contract lets him travel with a physiotherapist full time; it’s also gotten him onto the practice court with Shelton, 22, when they have landed at the same tournaments.

The first time they met, at the 2023 Mallorca Championships, Shelton figured out Fonseca was the new guy in the On team and suggested they practice the next day.

“I was like, ‘I am nothing and you want to practice with me?’,” Fonseca said.

He wasn’t nothing then and he certainly isn’t now. He won the U.S. Open junior title in September 2023, the season he became the first player from Brazil to top the junior rankings. In February, he smashed Arthur Fils in the first round of the Rio Open, 6-0, 6-4. At the time, the loss appeared to be a major setback for Fils, who is now ranked top 20 in the world and is the favorite for the Next Gen tournament, which begins today. They play each other in the last match of the first day.

That loss in Brazil has become more palatable for Fils ever since it happened. Fonseca started the year ranked world No. 727. He’s up to No. 145 now and he came within a couple of games of his first Grand Slam main draw in New York this August, losing to Eliot Spizzirri — four years his senior — in three sets in the last round of qualifying.

The obvious comparison to a top player is world No. 1 Jannik Sinner, given Fonseca’s big serve, easy baseline power and shy demeanor on the court and off it. Fonseca hums along like a flywheel, ready to whip his opponent off their axis when he leans into a forehand, or perhaps a two-handed backhand down the line. He can also change gear.

At the Madrid Open, Fonseca went a set down to Alex Michelsen, an American who is another rival in the 20-and-under bracket. Outplayed in cross-court forehand rallies, Fonseca started marmalizing balls straight down the middle and asking Michelsen to generate angles, pinging anything short to the corners. Michelsen couldn’t pass the exam: Fonseca served him a 6-0 bagel to level the match and prevailed in the third set.

“He is a player who can play his best under big pressure, and he has the ability to adapt fast to different situations,” his coach Guilherme Teixeira wrote over email. Teixeira has been working with his charge since he was 11; Fonseca’s mother, Roberta, has watched him play for much longer than that.

Roberta, who also answered questions over email, said she has never seen her son get nervous before a tennis match. She remembers him losing when he was eight or nine because he kept volleying balls that were heading out back into play. He was seriously upset leaving the court, but as soon as he saw his mother he started begging her to sign him up for another tournament.

None of this, including qualifying for the Next Gen Finals, guarantees anything. Alcaraz and Sinner both won it on their climb up the tennis mountain, but the tournament has also featured younger versions of Alexander Zverev, Stefanos Tsitsipas, Daniil Medvedev, Taylor Fritz, and Casper Ruud — all of them Grand Slam finalists but just one of them, to date, a winner. Medvedev won the U.S. Open in 2021. Many of the fabled eight at the end of each season have never gotten close.

Fonseca is in this year’s lineup alongside Fils and Luca Van Assche of France; Michelsen, Learner Tien and Nishesh Basavareddy of the U.S.; Jakub Mensik of the Czech Republic and Shang Juncheng of China, who also goes by his Americanized name, Jerry Shang.

It’s hard to say whether there are any Grand Slam finalists in that group, especially in tennis. The kids with the swag and the spots at Les Petits As may be alright, but wariness in the face of teenage hype is the far safer posture. Brazil hasn’t produced a top men’s tennis player since Gustavo ‘Guga’ Kuerten, the three-time French Open champion and former world No. 1 who helped revolutionize tennis with his early adoption of polyester strings.

For decades, players from the country and the rest of South America have had to overcome their rearing almost exclusively on red clay. It’s a far greater challenge for them than for players from other red clay hubs like Spain because of the distance that South Americans have to travel to find different playing surfaces and opponents. There is no wonder that young people tend to gravitate to the far more accessible game of soccer instead, before getting to talk about the influence of World Cup trophies, Ronaldo Nazario and Neymar. To play tennis in Brazil, you mostly have to be a member of a private club.

Fonseca remembers traveling to Europe to compete for the first time when he was about 13. He played on a public court in Germany with a picturesque view. Tennis balls appeared free and unlimited.

“In Europe, you have so much more help,” he said.

He was lucky enough to be born into a family of means with sports-mad parents. His mother flirted with professional volleyball. She and her husband, who competed in junior tennis in Brazil as a teenager, have run half-marathons and competed in road and mountain cycling and adventure races.

“Sport runs through our veins,” Roberta said.

Joao played just about anything they offered to him, including soccer, volleyball, swimming, judo, skateboarding, surfing, and skiing, plus tennis. His mother said he excelled at all of them.

At six, he would score all the goals at soccer tournaments for his academy while also chasing back on defense. He could swim all four strokes from an early age, and his swim club bumped him to the competitive team. He achieved his purple belt in judo at 10.

Teixeira spotted his tennis potential when he first saw him at 11. The quality of his shots, his pure contact with the ball, was far ahead of other kids his age and older, but there was something else he noticed. Wins didn’t excite him all that much and losses didn’t make him all that sad.

“On tour, you need to compete and practice week after week and be able to manage your emotions,” Teixeira said. “He just resets his mind and starts again.”

In the last year, Fonseca’s first as a full-fledged professional, Teixeira has seen him dial up that dedication. He is treating tennis as his career for the first time, engaging in practices and gym sessions with what Teixeira describes as a new level of seriousness.

This is a typical training day schedule for him, which begins with tests on his muscles to determine how hard he can go that day:

- 8:30 a.m.: Tests

- 9 a.m.: Physiotherapy and warm-up

- 10 a.m.: Gym

- 11 a.m.: Practice on court

- 1 p.m.: Lunch and rest

- 3 p.m.: On court

- 4:30 p.m.: Gym

- 5:30pm: Physiotherapy, if needed

Teixeira said Fonseca is also paying more attention to his rest and what he eats. He is diligent with breathing exercises that can help him stay calm during matches. Improving his footwork is high on the agenda for 2025.

Fonseca is still a teenager, though. He can only manage a month or so away from home before fatigue and homesickness set in. This season, he tried to play tournaments for four or five weeks, before returning home for a couple weeks of training and seeing his friends and family.

He’s still a teenage tennis player too. His biggest challenge is consistency: figuring out how to win when he isn’t playing his best. In junior tennis, the better player — the one with the best technique and the best shots — usually wins the tournament. That’s not how it shakes out during the serious stuff.

“In the pro tour, there’s a lot of players that can find the solutions, and the ones that find more solutions during the tournaments, during the weeks, they have better results,” Fonseca said. He went 7-7 in ATP matches this year; not bad for an 18-year-old. Sinner was 11-10 in 2019, the year he turned 18.

Fonseca has time, but for some things he is impatient, especially shaking that assumed allegiance to red clay and slow courts. Instead, he wants grass to be his best surface one day

“I love Wimbledon,” he said. “I want to be like Sinner or (Novak) Djokovic. Those guys that play good on any surface.”

(Top photo: On)