The night before the final day of Rickey Henderson’s professional baseball career, he concocted a makeshift drink that his team called “Championship Juice.”

The moment didn’t come with the Oakland Athletics or with any of the other eight clubs the first-ballot Hall of Famer played for over his 25-year big league career.

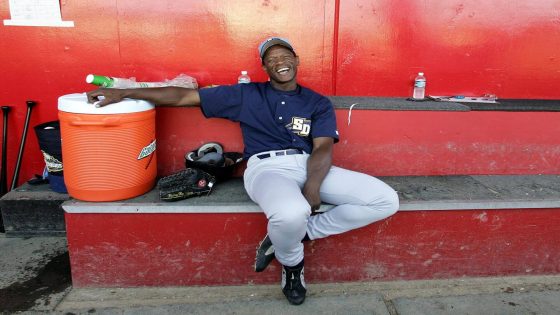

This was the San Diego Surf Dawgs, an independent league team that Henderson played for in 2005, at 46 years old, in one final hope of returning to the majors. The Surf Dawgs — whose jersey currently displays a dog clutching a surfboard — would be the last uniform the Man of Steal wore during his playing career.

The world knew Henderson as brash and boastful. His reputation was that of someone obsessed with his own image, speaking of himself proudly in the third person. But the players on this team knew better.

They knew a man they grew to love. A mentor whom many mourned with tears in their eyes following the announcement of his death over the weekend.

“The rumor was that Rickey was a selfish player,” said Seth Pietsch, a teammate in San Diego. “But man, he was just the most giving person. He was one of the coolest guys I’ve ever been around.

“Maybe it was that way when he was younger, I don’t know. But he definitely was not that way the last season that he played. He just wanted to do everything to help out.”

As his final team grieved, they also celebrated the man who was there for them. The man who poured Steel Reserve malt liquor into a bucket with Boone’s Farm fruit wine, mixed it together and drank it before winning the inaugural Golden Baseball League title.

The Surf Dawgs swept a doubleheader to secure a championship a day later. Henderson — who had two World Series rings already — partied like he’d won another.

On a team full of ballplayers in their young-to-mid 20s, he was more than double some of his teammates’ age. But that day, he was a kid again.

“At the moment we won the championship, he was the one that grabbed the ice bucket,” said teammate Darren Doskocil. “And he was the one that doused (manager) Terry Kennedy. I mean, he was jumping around just as much as we were.”

Henderson was the team’s everyday leadoff man, posting an .859 OPS, walking 73 times in 73 games, and going 16-for-18 on stolen bases. In some ways, he was just one of the guys. His teammates felt comfortable enough with him to razz him about his old age.

But in most other ways, it wasn’t that they were in the presence of a living legend. Kennedy, who played against Henderson as a long-time big league catcher himself, asked Henderson to give the team a tutorial in base stealing — a task he gladly accepted.

“I was watching our guys listen,” Kennedy said. “And I looked over, and the visiting club was in the dugout, and they were all up on the edge. I said, ‘Come on out here, let’s go.’ They all got a lesson from the greatest base stealer.”

From time to time, Henderson would eschew the bus in favor of driving himself to games. But that was about the only way he leveraged his status. He embraced this team.

Henderson certainly didn’t go out every night. But he picked and chose his spots. And whenever he did, he’d tell the team a time and a place. They’d meet there, and he’d treat everyone. The tab was his.

Doskocil remembers inviting his best friend to one of these outings. He introduced him to Henderson, uncertain of how the interaction would go. Remembering it now, Doskocil was sobbing.

“He said, ‘Any friend of Darren’s is a friend of mine for life.’”

“It wasn’t like Rickey and I were close,” said Doskocil, who was playing the last of nine years in independent ball that season. “That was just the teammate he was.”

Steve Smythe, a pitcher, was one of only two other players on that team who had been in the big leagues before. He’d posted a 9.35 ERA over eight games with the 2002 Cubs. A team with the likes of Fred McGriff, Sammy Sosa and Kerry Wood.

Still, Smythe, a baseball card collector, was nervous to approach Henderson about signing one with his likeness. Smythe had dozens of Henderson cards and was shocked to hear Henderson say he was willing to put his signature on all of them. Or at least the ones his endorsement contracts allowed him to sign.

“He was going through them — ‘I can sign those, I can sign those, I can’t sign those. I can sign that one.’ He was like, ‘I’ll sign them all, whichever ones you want.’ I was like, ‘Are you serious?’ … I’m like, s—, I’d just be happy with one.”

“I feel fortunate enough to have had the encounters or getting things like that in person. Guys look at that and see a baseball card. I look at that and see my teammate.”

Every home game was a sellout that season. The games were played at San Diego State University. Fans were all there to see Henderson, of course. But it was Scott Goodman who was the team’s best player, leading the team in homers and RBIs.

Goodman said the first baseball game he attended as a kid was in Oakland, where he saw Henderson hit a leadoff home run. He kept Henderson’s poster in his room. Now, he had the locker next to him.

“He would act like he was impressed with what I was doing,” Goodman said. “I always was awestruck that he would think my swing or my approach was impressive. He did that with a lot of guys, not just me. He used his status to provide more joy to our lives.

“He had a certain rep out there. And I think it’s the swagger and confidence he played with. But he really cared about people a great deal — even independent baseball players who had no business sharing a field with him.”

To this day, that is how he’s remembered by this group of guys. For most, playing with him was the highlight of an otherwise forgettable baseball career.

Mike Leishman never played in the majors. He never even played in affiliated baseball. Just three unremarkable seasons of indy ball. But about three months ago, he took a team of 12-year-olds that he coaches to a baseball tournament in Cooperstown, New York. To the Hall of Fame.

He took the team to Henderson’s plaque and regaled his team with stories from that season. Leishman wanted to teach his team about Henderson, because of the way he played the game. The passion he displayed was a valuable thing for his young players to understand.

As they stood there, Leishman said he turned around. And, by pure happenstance, there was a Surf Dawgs teammate, Jeff Blitstein, standing behind him. An uncoordinated moment of fate to see a friend whom he hadn’t talked to in nearly two decades.

“It was one of those crazy moments,” Leishman said. “And it was because of Rickey. He was there with his father, doing the same thing. Telling stories to his dad about what it was like to play with Rickey.

“The idea of me bringing 12-year-olds and Jeff bringing his father was a cool moment.”

That’s the impact that Henderson had on the game. All the stolen bases were great. Talking in the third person, as he was wont to do, was a fun personality quirk. The two World Series championships. All the various awards.

But Henderson’s legacy is also seen in this team of Surf Dawgs. And how, over five months, he impacted the lives of everyone on that team forever.

“That’s the thing about Rickey,” said Kennedy. “He believed that he could, and he did. It sometimes came out as raw egotism. But when you know him, I don’t think so. He was so talented. He knew it, and he could make it happen.”

(Photo of Rickey Henderson from 2005: Lenny Ignelzi / Associated Press)