The axe has fallen. Erik ten Hag has gone.

Just as things looked brighter for Manchester United after the international break, the grey clouds returned.

Sunday’s 2-1 loss to West Ham United saw Ten Hag’s side spurn multiple chances before a late Jarrod Bowen penalty consigned them to their fourth loss in eight Premier League games.

The evidence for the Dutchman’s dismissal was just too overwhelming.

United sit 14th in the league table with 11 points on the board, which is their second-lowest tally after nine games of a Premier League campaign — only logging fewer at this stage in the 2019-20 season (10). Only Crystal Palace and Southampton have scored fewer than United’s eight goals so far this season. The last time United had scored eight goals after nine games in a league campaign was in 1973-74 (they were relegated).

The surface-level numbers make for miserable reading, and a look under the hood casts an even sharper lens on the long-term issues at Old Trafford.

Here, The Athletic provides a guided tour of their woe, via 10 data visualisations that track just how bad things have become.

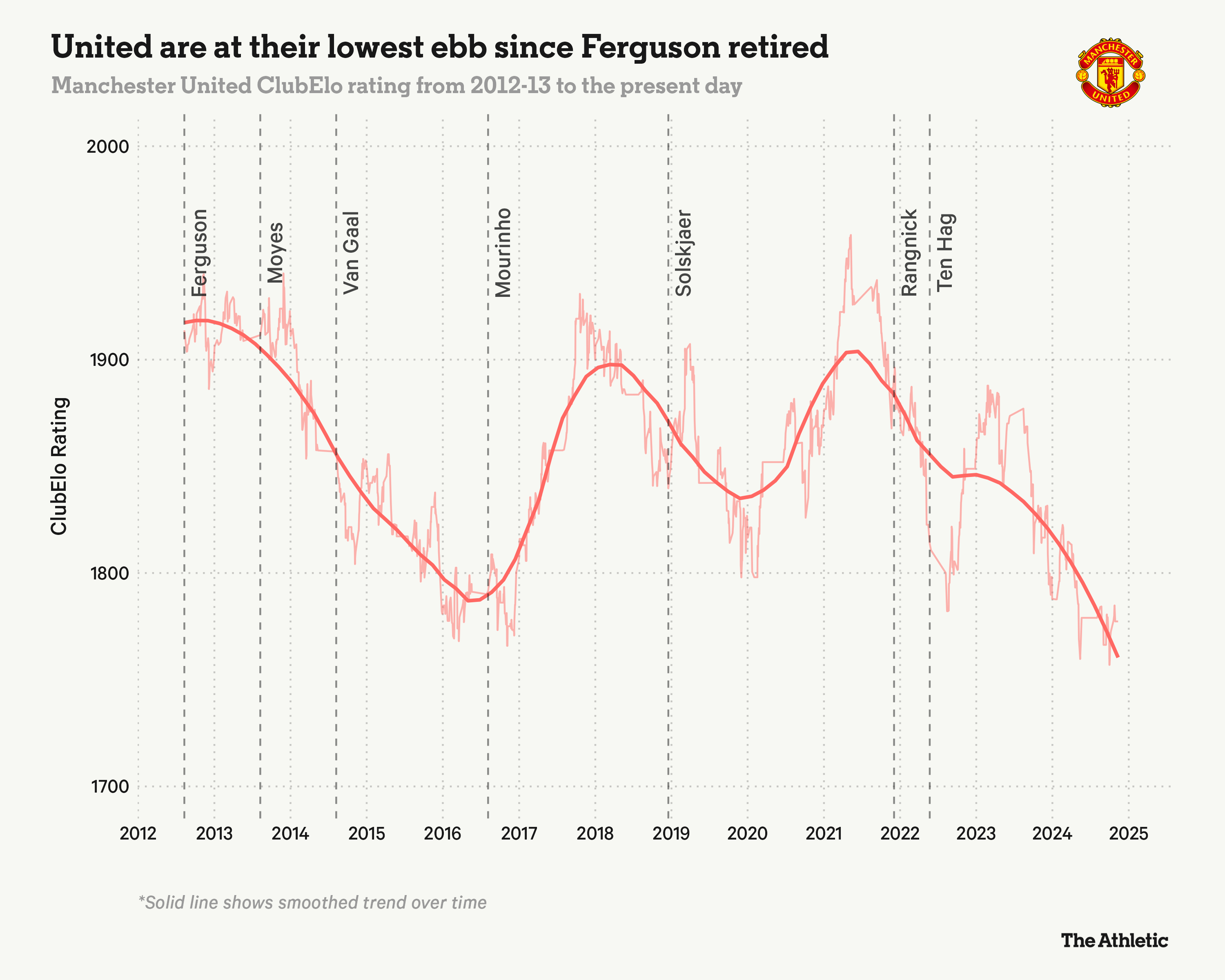

First, an indication of just how badly United’s stock has fallen among the European elite.

Using data from ClubElo — a measure of team strength that allocates points for every result, weighted by the quality of the opposition faced — we can track United’s rating over the last decade and beyond.

Peaks and troughs are typical of any team, but the graphic below highlights how United’s dominance has declined on the pitch. After a notable slide following Sir Alex Ferguson’s retirement in the summer of 2013, fortunes picked up under Jose Mourinho and Ole Gunnar Solskjaer.

However, there has been little reason for optimism since Ten Hag arrived when United’s ClubElo rating hit an all-time low in the post-Ferguson era.

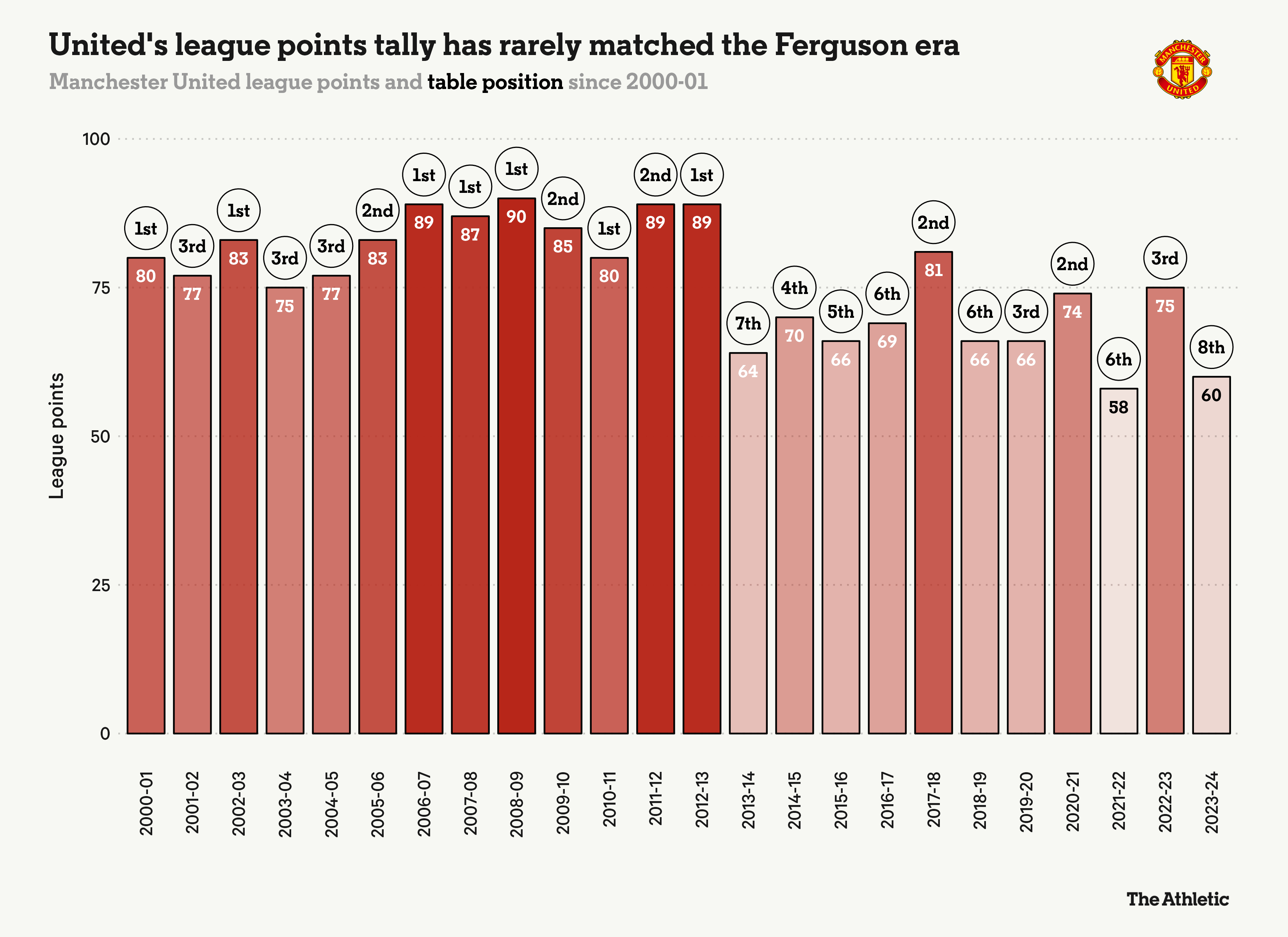

Comparisons with the glory days are inevitable, but it is only when you map out United’s Premier League points tally over time that the scale of the issues becomes clear.

Looking at their final tally since the turn of the century, there is a tangible drop-off from Ferguson’s final season in 2012-13. Only 2017-18 saw a points tally above 80 (under Jose Mourinho), with last season’s eighth-placed finish under Ten Hag being United’s worst league position in the Premier League era.

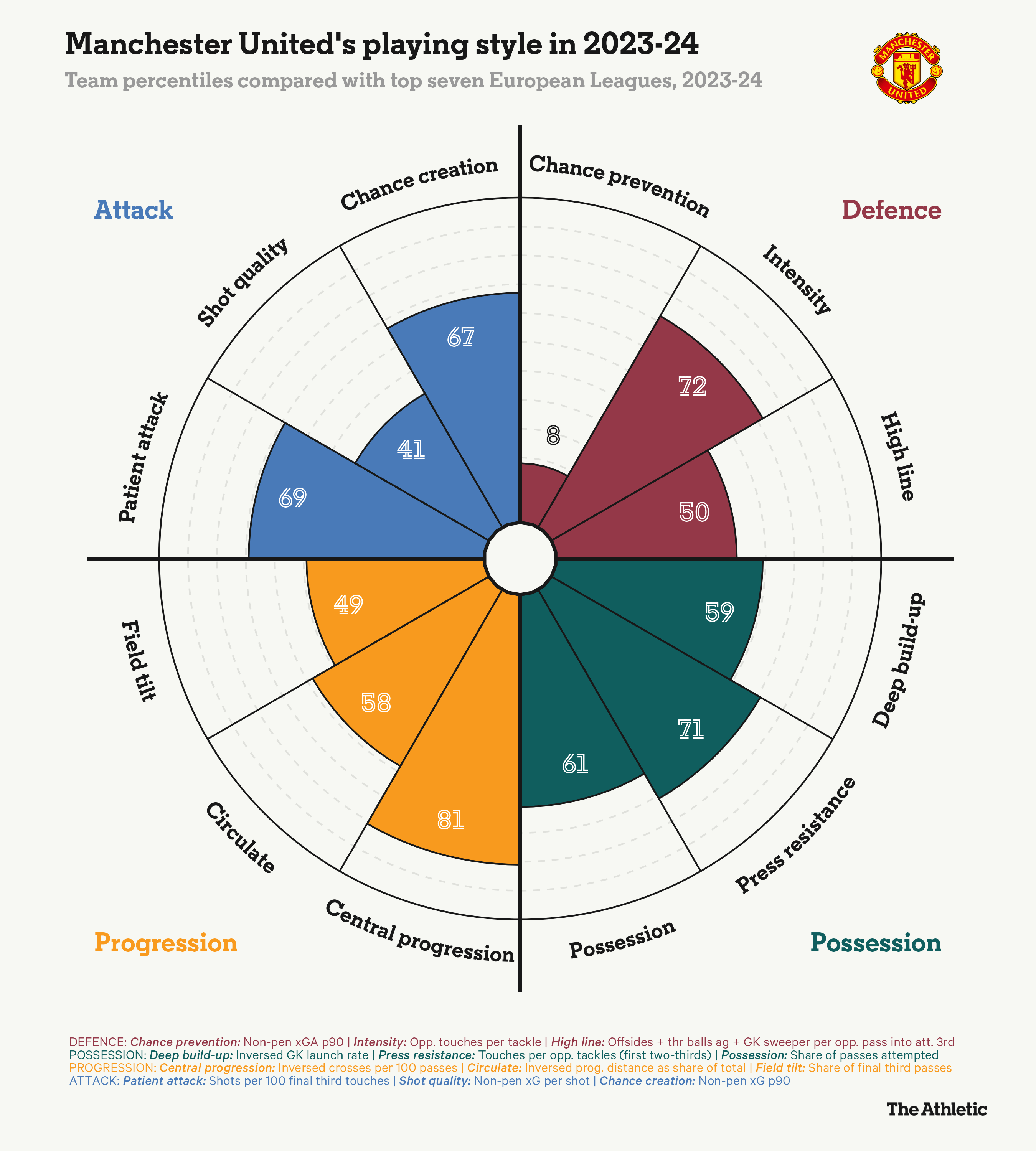

So what went wrong last season? It is worth looking at the style Ten Hag was trying to impose on the pitch using The Athletic’s playstyle wheel, which outlines how a team looks to play compared with Europe’s top seven domestic leagues.

This gives us a broad idea of a team’s approach in and out of possession. If you looked at Manchester City or Arsenal’s playstyle wheel last season, it was possession-based. If you looked at Liverpool’s, it was transitional and direct.

Looking at Manchester United’s playstyle wheel for last season, and it was… confusing.

With one of the poorest defensive metrics in Europe (Chance prevention: eight out of 99), and a share of the ball that was just over average (Possession: 61 out of 99), United’s approach was largely based on counter-attacking (Circulate: 58 out of 99) rather than territorial dominance (Field tilt: 49 out of 99).

That style has rarely been clearly defined under Ten Hag, making any analysis of their “game model” a difficult task. It might sound reductive, but if you strip out style, any elite club should at least be strong in both boxes; that is, create chances of higher quality than you concede in the average game.

That cannot be taken for granted at Old Trafford in recent seasons.

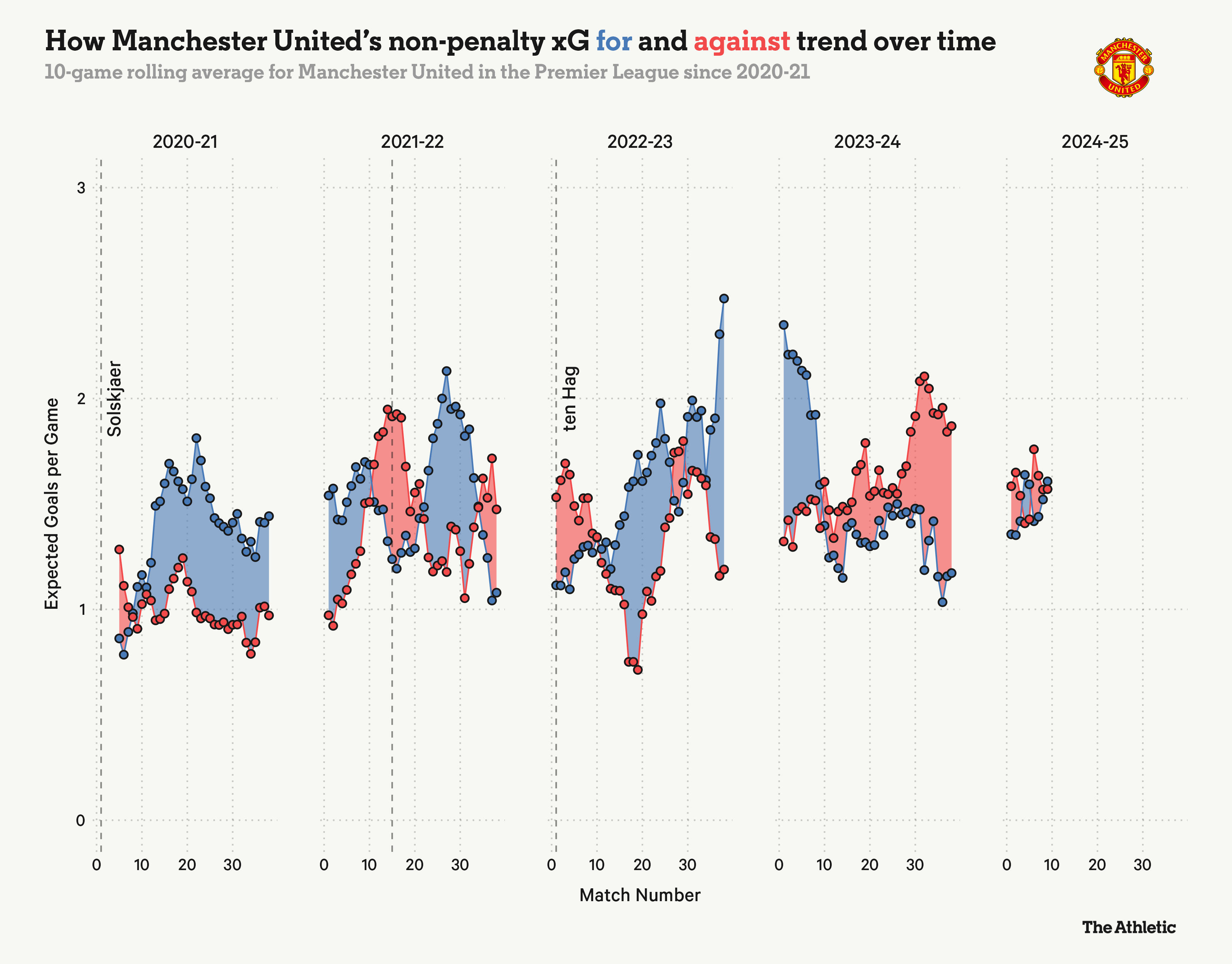

Looking at United’s 10-game rolling expected goals (xG) for and against paints an equally confusing picture. Typically, you would expect to see dominant sides consistently create more chances than they concede (denoted by the blue shade with higher xG than xG against).

But under Ten Hag, there is barely a sustained period where that is the case, with last season often seeing the opposite (denoted by the red shade with higher xG against than xG for) which is not befitting of a team looking to push for European places, let alone a league title.

Why might this be? United’s bluntness in attack has been a problem for over 18 months now. Marcus Rashford’s decline in form has not helped, but the chronic issue has been that Ten Hag’s side did not have distinguishable — or repeatable — attacking patterns that looked to unlock opposition defences.

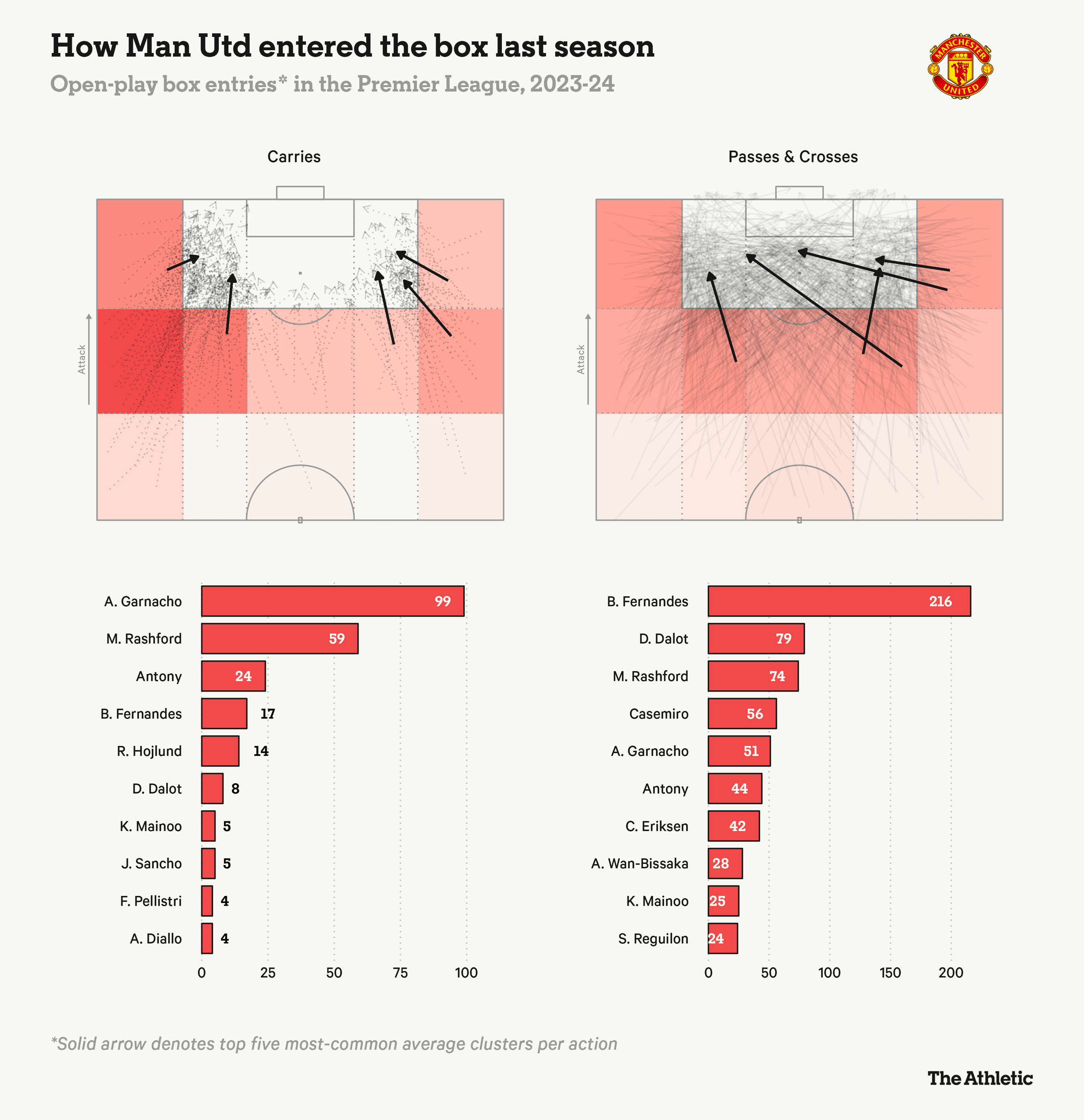

United’s approach to getting the ball into the box last season was revealing, particularly when you see the sheer scale of Bruno Fernandes’ actions. Not only was he the man most likely to feed the runs of United’s wingers to subsequently carry the ball, but his 216 passes or crosses into the box were more than double his nearest team-mate — pointing to a notable skew and a one-dimensionality to United’s delivery.

United were not a cross-heavy side under Ten Hag (only Sheffield United averaged fewer than their 1.3 crosses per 90 last season) but greater variety has been needed in their delivery.

Luke Shaw was sorely missed at left-back, but the graphic above can go a long way to explaining why Rasmus Hojlund was growing increasingly frustrated that his runs towards the six-yard box were rarely found.

Fernandes is the catalyst for most of United’s forward play, but his ‘hero-ball’ high-risk, high-reward passes can often lead to attacking cul-de-sacs. Giving up possession so frequently also left his side notably vulnerable on the counter-attack, with United rarely generating a solid rest defence in possession to stave off transitions.

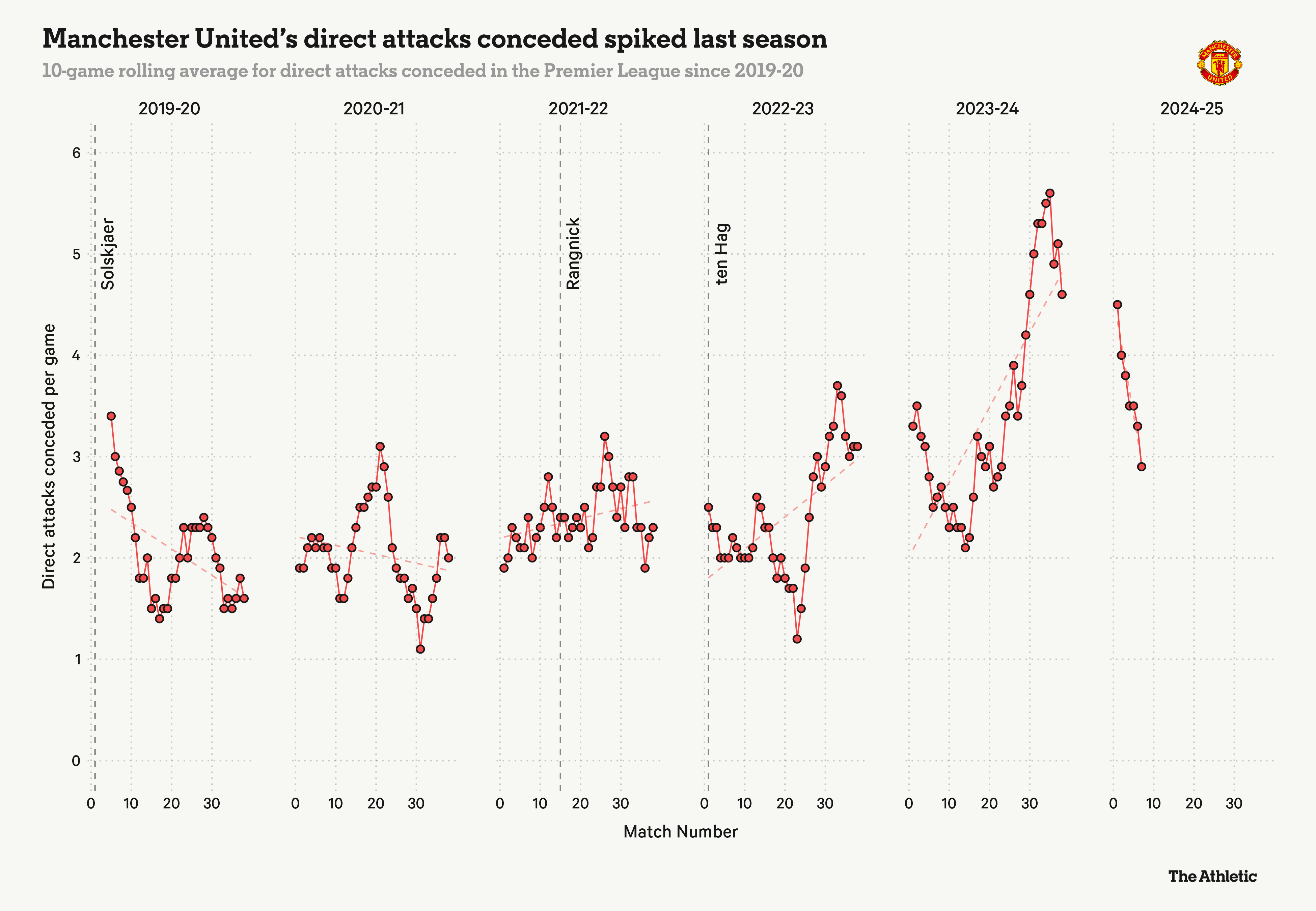

That is underpinned by the number of ‘direct attacks’ United conceded — possessions that start in a team’s half and result in either a shot or a touch inside the opposition penalty area within 15 seconds. In 2023-24, United’s rate of 3.4 direct attacks conceded per 90 minutes was their worst of the past six seasons, and their rolling 10-game average below highlights that sharp spike that saw them hopelessly vulnerable out of possession.

The swarm of retreating players would often leave gaps between the defence and midfield. As United’s defensive line overcompensated by dropping too deep, it provided opponents with opportunities to exploit the spaces via cutback situations. Only four Premier League teams conceded more chances from cutbacks than United’s 68 last season — three of those, Sheffield United, Luton Town and Burnley, were relegated.

Beyond the mitigating factors of injury issues last season, United looked to address their defensive problems in the summer with the arrival of centre-backs Leny Yoro and Matthijs de Ligt — a pair designed to help Ten Hag’s side squeeze the pitch and be more compact within those defensive transitions.

With Yoro injured, the most common centre-back pairing has been De Ligt and Lisandro Martinez. Both were dropped in United’s goalless draw with Aston Villa before the international break — replaced by Harry Maguire and 36-year-old Jonny Evans — with four centre-back partnerships named in the starting XI in the opening nine Premier League games.

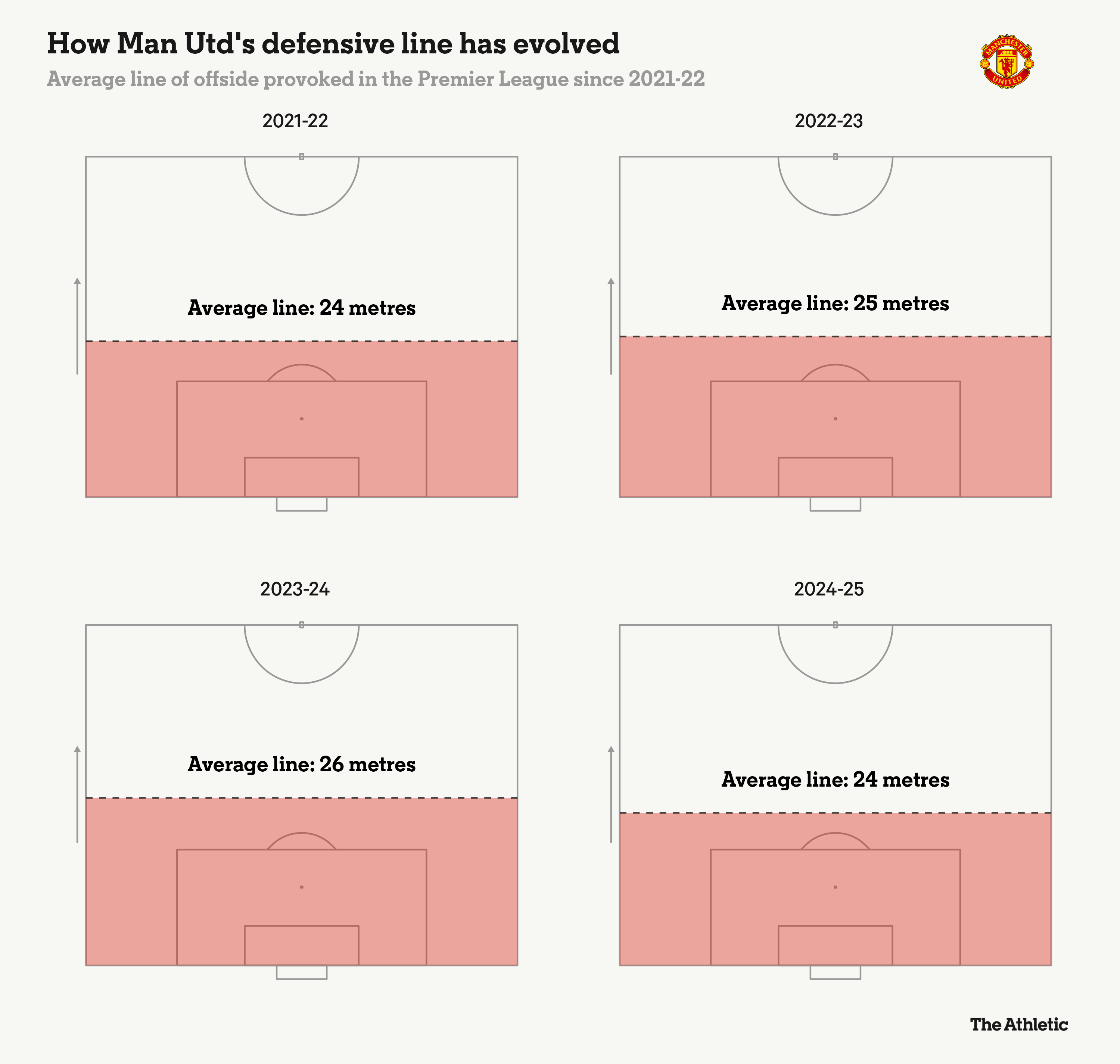

Using the height of United’s average offside line as a proxy for their defensive line, we can track their change across recent seasons. Sure, we are just weeks into the current campaign but there is little evidence to suggest Ten Hag made a tangible shift in United’s aggression off the ball. It was — quite literally — one step forward and two steps back in his time as the club’s manager.

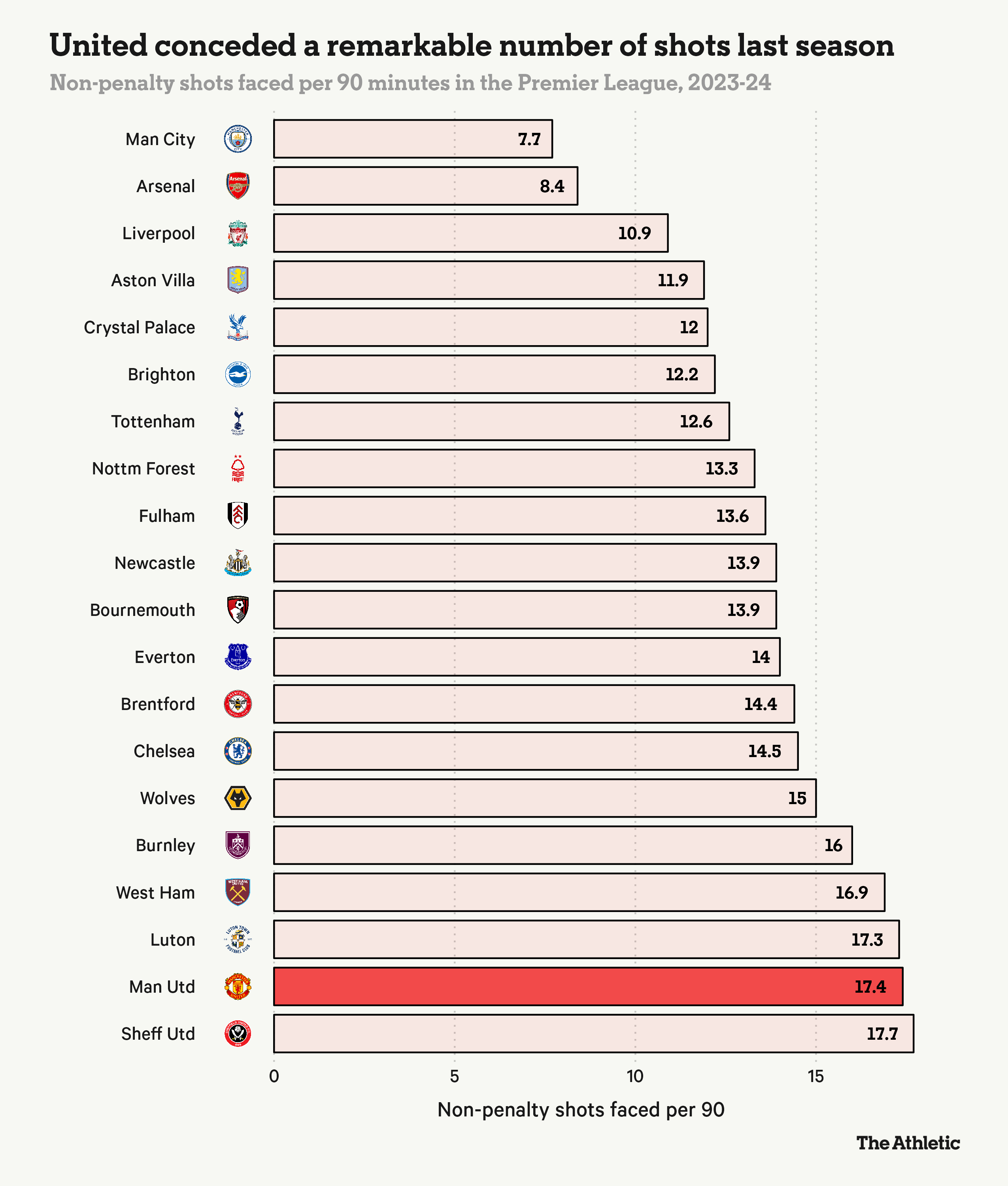

United’s shift to a 4-2-4 structure out of possession this season was an attempt to make them more compact during opposition build-up. This has seen mixed success, but it was clear that Ten Hag needed to tighten things up when considering the number of shots they conceded in 2023-24.

Injury-plagued season or not, United’s 17.4 non-penalty shots conceded per 90 minutes on average was topped only by relegated Sheffield United. A total tally of 667 shots conceded was more than 2007-08 Derby County, who won one game all season and finished the campaign with only 11 points.

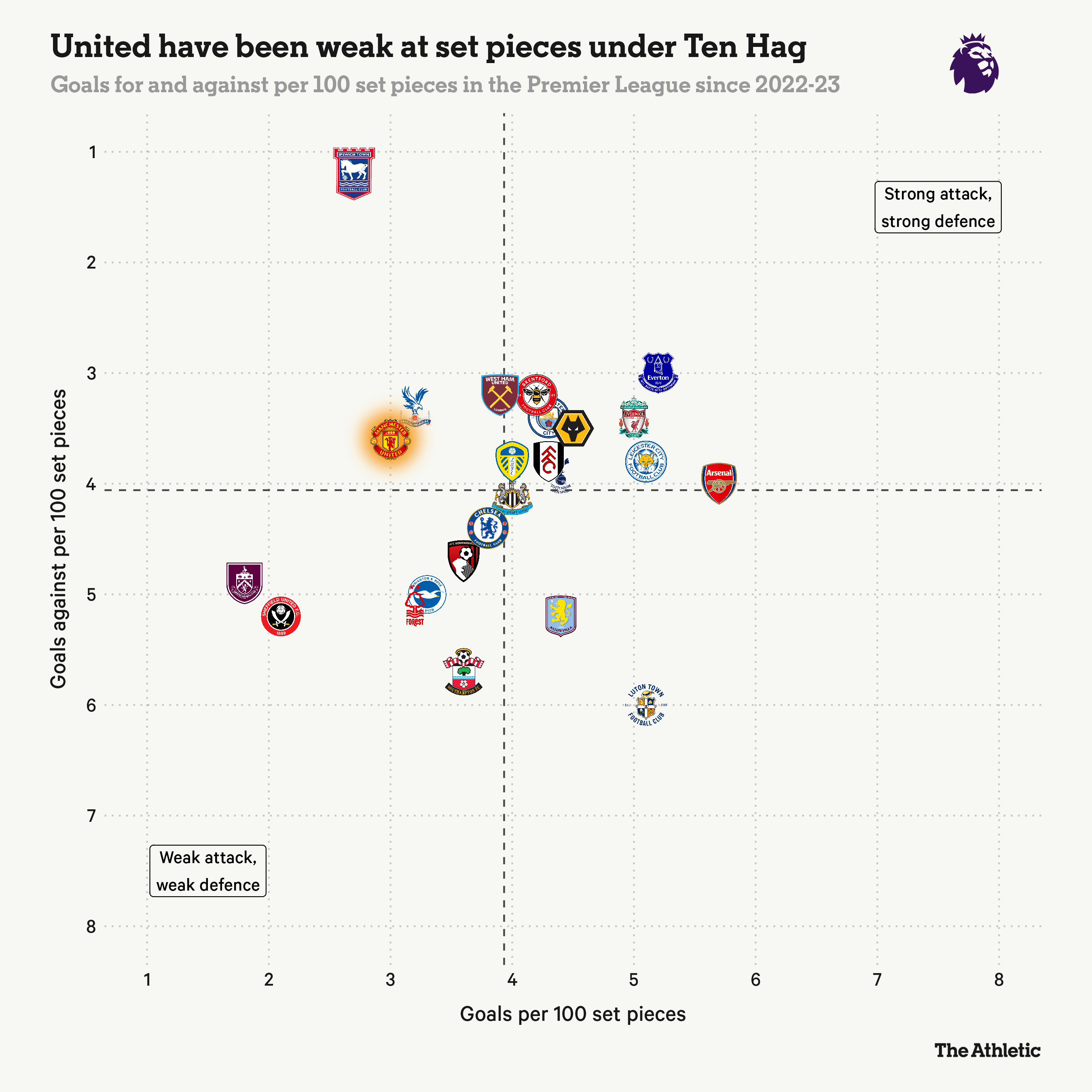

Things were not much better when isolating United’s set-piece performance last season, which is becoming an increasingly important part of the game. They were not wholly leaky in defence, but United’s 3.3 goals scored per 100 set pieces — accounting for opportunity across all teams — was the sixth-worst rate in the league.

Broaden that out across the whole of Ten Hag’s tenure since the start of 2022-23, and United’s set-piece prowess leaves little room for optimism in attack. Only the efforts of relegated Burnley and Sheffield United and promoted Ipswich Town have been poorer in that period.

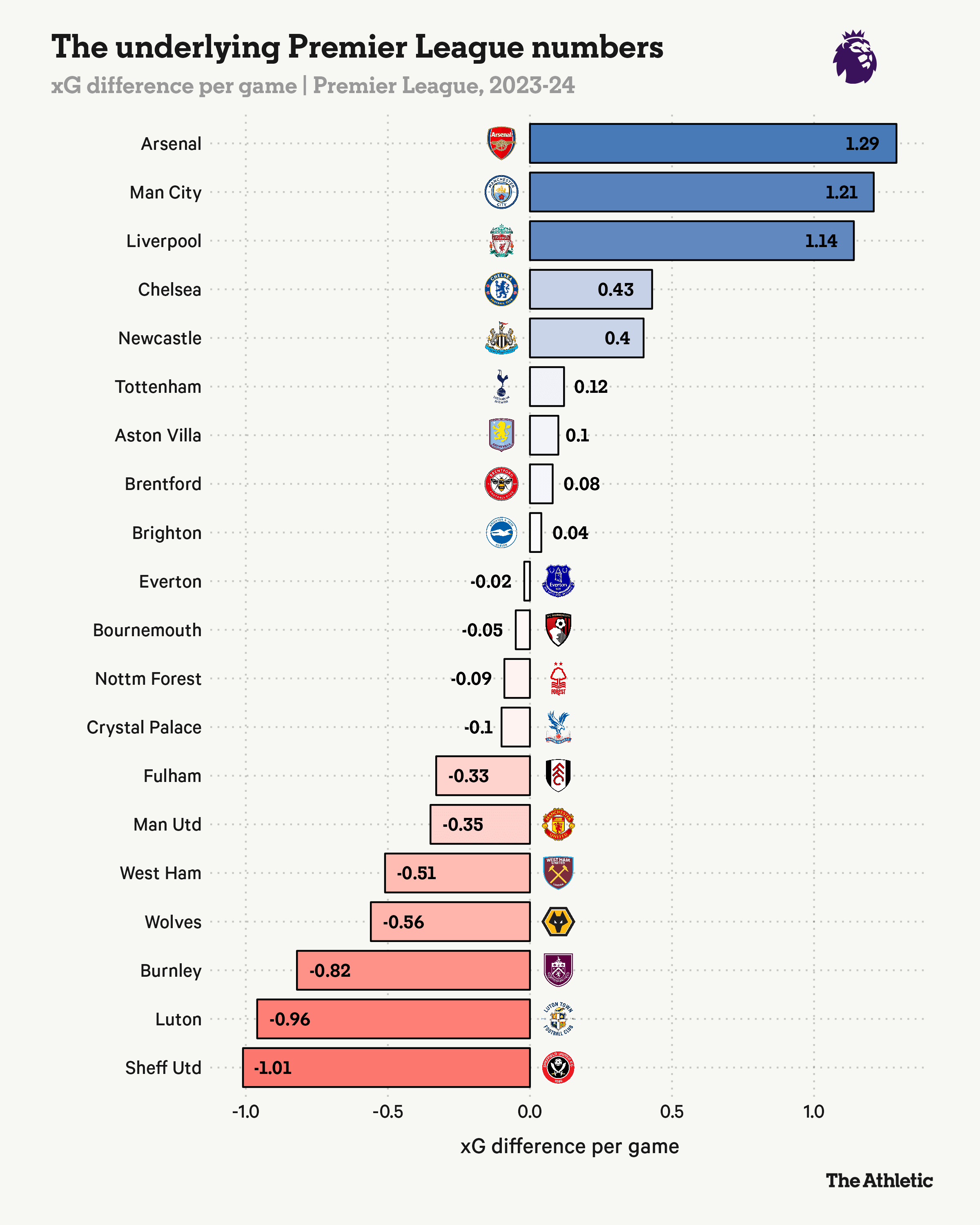

Combine last season’s poor performances in both boxes and it makes for worse reading than the actual league table.

Using expected goal difference per game as a proxy for where each team should have finished — based on the chances they created and conceded — United’s 15th-place finish was a shocking return across a full season. An FA Cup win salvaged some hope, but there were few positives to take from a turbulent 2023-24 season in the league.

The opening nine games of this season have moved the dial slightly, with United’s 0.11 xG difference per game being good enough for… 10th-best in the league. They have had some poor luck in front of goal in the opening weeks, but the numbers suggest that Ten Hag’s side are still some way off where they should be.

Statistics can sometimes be used to shape a narrative that someone wishes to tell. However, the converging evidence above was just too damning and goes some way to explaining why change was needed in the dugout.

(Top photos: Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)