“This is heartbreaking, not even the goalposts are there any more. This stadium is just gone. The wave came and just swept everything away. We’ve nothing left. This is sad, really, so sad. I understand the pain of those who have lost loved ones. But for me, this stadium was my life, my second home.”

Mari Carmen Sanchis is club delegate and press officer at CF Paiporta of the Primera FFCV division in the seventh tier of Spanish football. Founded in 1922, the team from a small town in Valencia’s Horta Sud suburbs has played at its El Palleter stadium since 1972.

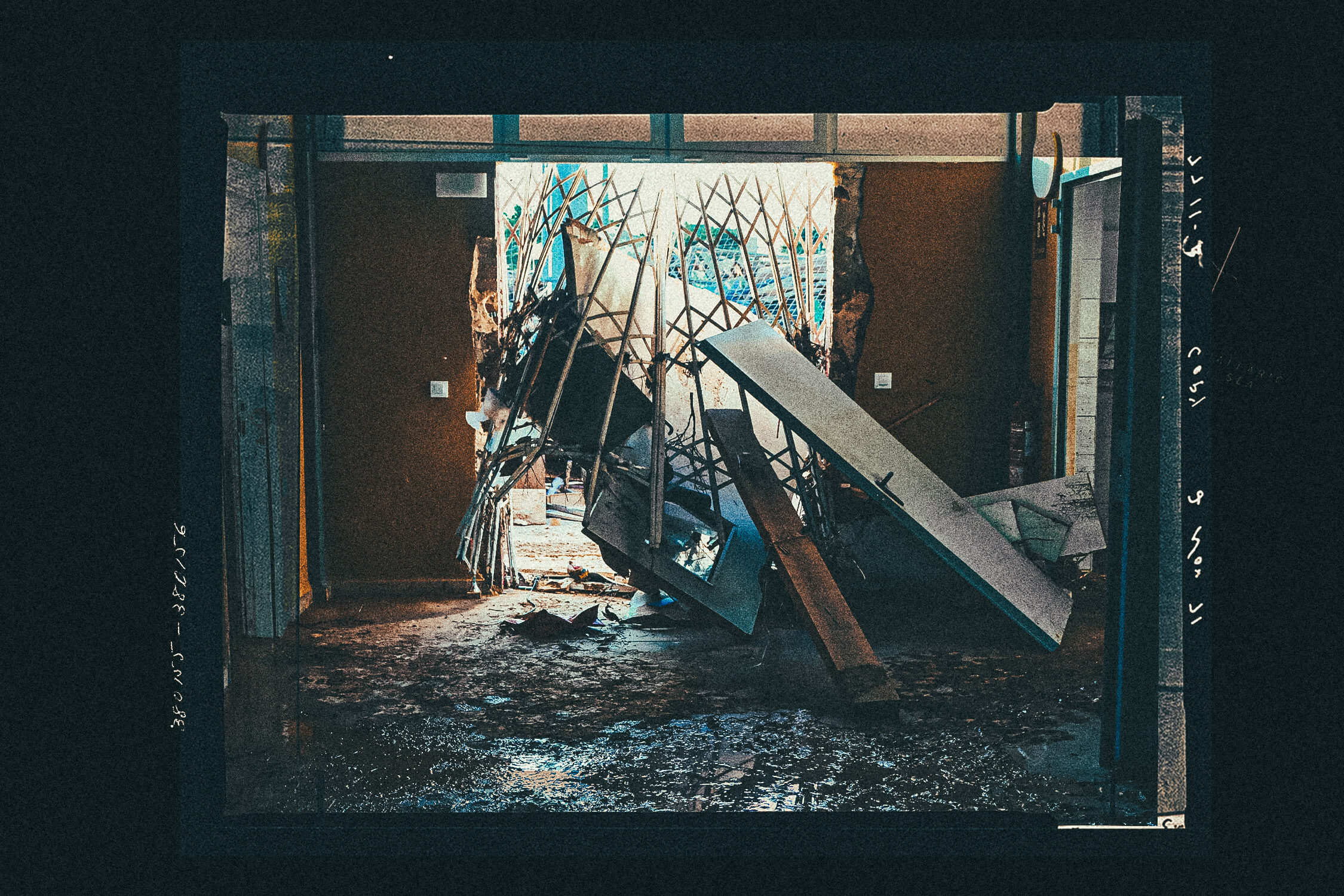

A drainage gully which carries water down from the Valencia region’s interior highlands towards the sea runs right past where El Palleter stands. Or used to stand. The playing surface is now a wasteland of mud and water strewn with huge lumps of concrete, steel oil drums, plastic bottles and chairs carried from a nearby primary school.

El Palleter was destroyed when vicious storms hit on October 29 and 30. At least 223 people have been confirmed dead in Valencia. Spain’s prime minister Pedro Sanchez has described the floods as the worst natural disaster in the country’s recent history.

A week later, Sanchis and her husband Carlos brought The Athletic by car to Paiporta. A police check-point was only allowing vehicles carrying emergency material to enter the town centre. Walking the last kilometre to El Palleter, we passed overturned car wrecks and piles of debris including mattresses, iron railings and wooden furniture. Army helicopter flew overhead and emergency service sirens could be heard nearby.

At the stadium, a dark brown water mark runs across a wall at more than two metres above pitch level. The dressing room roof had fallen in. Water still covered the floor of the ruined club offices and bar. The stadium scoreboard had been picked up and thrown down by the water. Boots and jerseys lay scattered around in the mud.

“This stadium was built by so much work from so many people,” Sanchis says tearfully. “The people in Paiporta are very warm, friendly. We’re a small club, so we all help each other out. We’ve celebrated promotions, suffered relegations, everything. But this is the hardest thing. We’re going to have to start again from zero. It’s very bad, very sad, a nightmare.”

Valencianos are accustomed to the DANA or ‘gota fria’ (cold drop) heavy rains which can occur in autumn. After previous flooding in 1957 which caused 81 deaths, according to official figures, and heavy damage, the Turia River was redirected out of the city centre in a project — the Plan Sur — which concluded in 1972.

But Tuesday, October 29 brought a storm more serious than most had ever experienced. Some areas suffered a whole year’s worth of rainfall in less than 24 hours. Mistakes by local government officials meant warnings from Spain’s AEMET state meteorological agency were not widely communicated until very late. As the enormity of the situation became clear, people desperately scrambled to try to get home.

“I found myself in the epicenter of the storm as I live in Chiva,” Levante coach Julian Calero tells The Athletic. “That morning it had rained a lot. We were flying out that night to play the Copa del Rey, so we left the training ground earlier than usual, just after 1pm. That 90 minutes might have saved our lives.”

Water which had fallen inland started to flow down towards the sea, accumulating rapidly. Man-made gullies built to safely direct water flowing down towards the sea, called ‘barrancos’, were unable to cope.

“That evening, from my house’s balcony you could see a huge amount of water running past, across the golf course next door,” Calero recalls. “We were not afraid for ourselves, but we knew that water was going to cause damage elsewhere.”

Manises CF, who play in Lliga Comunitat Grup Nord Senior (Spain’s sixth tier), had been preparing to host Primera Division Getafe in the Copa the following Thursday. Manises coach Santi Marin told The Athletic that people close to the drainage gully could see water levels rising and knew a disaster was coming.

“The ‘barranco’ is 70 metres deep and almost 100 metres wide,” he says. “But it overflowed. The power of the water was tremendous. A huge wave destroyed everything in its wake, carrying away various bridges. Drivers had to get out and leave their cars on the road. When people saw the water coming, they tried to climb up high, some into trees. But the water was so strong it even ripped up and carried trees away. People were dropping blankets and ropes from balconies to get others below to climb up. Garages were flooded within seconds.”

Among the victims was Jose Castillejo, 28, who was at Valencia’s academy as a teenager, then played in midfield for local teams Paterna, Eldense, Bunol, Recambios Colon, Roda, Torre Levante and Villamarxant.

“I played against Jose Castillejo,” Marin says. “He was a former team-mate of my players (at Manises). He was a good guy, football was his life. And the water took his life away.”

Sanchis had a loss in her family. “My sister in law’s father went out to move his car and did not return,” she says. “Three days later they found his body at the bottom of the ‘barranco’.”

At La Liga level, family members of senior figures at Levante were among those who died, while a club physio’s business premises was completely ruined by flooding. The families of Valencia players Rubo Iranzo, Cesar Tarrega and Yarek Gasiorowski, and team manager Voro, had houses seriously damaged. A Los Che staff member had to be rescued from his home, and is now temporarily living with the club’s corporate director Javier Solis and his family.

“It’s been very difficult, an extreme situation,” Solis tells The Athletic. “Nothing so serious, which affected so many people, has happened in living memory. We all know people who have lost vehicles, houses, businesses… entire families have lost everything, it’s devastating.”

As The Athletic visited different towns which had been flooded, streets were still covered in inches of sticky mud. Ruined household appliances, furniture and mattresses were piled on street corners. Emergency workers were pumping water up out of underground garages. Locals were cleaning the ground floor of their houses or shops with mops and brushes. Trucks were carrying detritus to dump on open spaces like playgrounds and car parks.

That was a week after the disaster. The scene in the hours and days immediately following the storm was much more horrific. More than 50,000 hectares was flooded, thousands of homes and business premises were completely ruined and more than 100,000 vehicles were destroyed.

“Our house was completely incommunicado for over a day — no telephone signal, no electricity, no water,” says Calero. “On Thursday, when we could finally leave, it was like a disaster movie, or The Walking Dead. Many cars strewn around, huge stones, people walking on the road, mud everywhere.”

Local police search and rescue operations were overwhelmed by the enormity of the situation. People rescued their neighbours from ground floor houses which had been blocked by material carried along by the water. Thousands of volunteers from elsewhere in the city walked to the most affected areas to help as they could.

Valencia forward Hugo Duro helped clean up streets and houses in Chiva, as did youth teamers Javi Navarro and Pedro Aleman in the nearby town of Guadassuar. Levante captain Vicente Iborra walked into Paiporta on Friday with his family — bringing bottles of water and a shovel to help clean up.

“I know that zone well, I’ve friends there, family, former team-mates,” Iborra tells The Athletic. “I played at Paiporta’s stadium as a kid. My son played there just a few weeks ago in a friendly, and we were there with him. The streets were just destroyed, a catastrophe had hit. There was a family who could not get out of their house.”

Por cierto, Don Vicent Iborra, con la familia y palas en mano, a coger la carretera que te lleva a Paiporta desde Valencia.

Honor. pic.twitter.com/8uMbr8hZsx— Macho Levante Out of context (@Macholevanteout) November 1, 2024

Former Valencia player and Barcelona sporting director Robert Fernandez, along with ex-Los Che team-mates David Albelda and Vicente Rodriguez, were part of the volunteer clean-up effort in the town of Catarroja in the days after the flooding.

“It was like a tsunami had passed through,” Fernandez tells The Athletic. “To see it with your own eyes was terrible. We brought water and stayed there the whole day to help, taking things out of the house, lots of earth and lots of water. People there are very desperate. It’s been horrible, families have lost everything. Many people have lost loved ones, parents, sons and daughters, brothers and sisters.”

Locals say the first days were very chaotic and disorganised, with little or no official guidance. There was a particular lack of the emergency expertise and logistics such as heavy machinery to clear streets. The death toll grew each day, and fears of disease mounted with standing water growing stagnant and vulnerable people unable to leave their houses.

Before becoming a professional coach, Calero combined playing lower level football with a job as a police officer for 15 years. The weekend after the floods hit, he went with his wife and daughter, a nurse, to bring medicine to people who needed it in Chiva and Paiporta.

“There were people with diabetes or other conditions who need medication every day,” Calero says. “People are very grateful for the help, for giving them your time, altruistically. Many have lost family members, others have lost friends, and others have lost all their property, their houses, their cars. Very humble people have lost everything. It leaves you with a very bad feeling in your body. It has been such a difficult week.”

🫶🏻🚐 Calicanto , Chiva, Manises.

Seguimos distribuyendo solidaridad por las localidades afectadas por la Dana 👏🏻

Gracias por vuestra hospitalidad.

🗣️ Aurelio y Ramona, vecinos de Calicanto. pic.twitter.com/O8oADMs6qy— Levante UD (@LevanteUD) November 7, 2024

The slow official response led to anger among the local community. When Spain’s King Felipe VI and Queen Letizia visited Paiporta on the Sunday after the floods hit, they had mud thrown at them. Spanish PM Sanchez and Valencian regional president Carlos Mazon were greeted by shouts of “murderers” and “get out”. Many The Athletic spoke to on the ground were angry at squabbling politicians more concerned with avoiding blame than taking responsibility.

“The organisation has been very bad; such situations need experts,” Calero says. “The army did not arrive as quickly as it should have. They are used to warzones, and this was like a warzone. They have very good professionals to organise everything — field hospitals, temporary bridges, channel water away, bring water in and organise the people (volunteering). But for political reasons, a regional government of one party, the central government another rival, this did not happen.”

The Athletic asked the Valencia regional government about the suggestion that it had not reacted quickly or strongly enough to help people affected by the flooding. A spokesperson responded with a list of the actions taken over the days of the disaster, while also pointing to the historic amount of rainfall during one 24-hour period.

Asked by The Athletic whether army personnel could have been on the ground quicker to help, the Valencian regional government said that the central Spanish government in Madrid had ultimate responsibility.

When The Athletic visited Levante’s Ciutat de Valencia on Thursday morning, there were big cardboard boxes with labels saying food, milk, blankets and clothes. Dozens of young fans, staff and youth players were ferrying boxes to vehicles waiting to bring them to the areas affected. During the week, local NGO ‘Chefs solidarios’ prepared paellas and other dishes which were packaged up to be distributed around the city.

Un Ciutat a pleno rendimiento 🫶🏻 pic.twitter.com/C66oGElGVF

— Levante UD (@LevanteUD) November 6, 2024

“Once we put out the call, the stadium soon started to fill up with tonnes of material,” Levante director Maribel Vilaplana told The Athletic. “Everyone has helped as they can — directors, men and womens’ teams, coaches. Staff have driven club vehicles to the affected zones. We’d no experience in this, but we’ve been able to channel this overwhelming solidarity. Almost everybody in Valencia has someone very close to them who has been affected. So we feel very proud of what we’ve been able to do.”

Valencia’s Mestalla stadium — home to the city’s other La Liga club — was also put to emergency use. Material such as forklifts, shovels, brushes, drainage pumps, generators and boots was collected. Los Che players including captain Jose Gaya, Pepelu and Dani Gomez helped organise the material donated. The club also partnered with local organisation Banco de Alimentos (Food Bank) who they had also worked with during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“More than a million kilos of food and materials was collected which is being distributed among the towns affected,” Solis says. “We’ve all been doing what we can. I went to Paiporta and Alfafar, and I’ll never forget what I saw.”

Other Spanish teams also sprung into action, with fans at clubs including Osasuna, Atletico Madrid, Deportivo la Coruna and Calero’s former club Burgos donating material.

When The Athletic visited a school in Paiporta being used as a distribution centre, some locals were dropping off bags of food, water, clothes, boots and blankets. Others came to ask if they could take things they and their families needed. People who had not seen each other since the disaster were meeting, sharing hugs and war stories.

Sanchis and her husband brought nappies and baby food to an elderly lady looking after two six-month old grandchildren in her flat, while their parents were trying to deal with houses which had been completely flooded.

“People have lost everything — their houses, their cars, their businesses,” Sanchis said. “All week we’ve been going around with a shopping trolley, distributing blankets and food.”

Osasuna coach Vicente Moreno missed his team’s Copa del Rey game last Tuesday, as he was in Massanassa helping clean up his family home. Among the volunteers helping out in the affected areas over the weekend was Barcelona and Spain forward Ferran Torres, who was in Valencia’s academy at the same time as Castillejo, the former footballer who died in the flooding.

Torres was absent for Barcelona’s game against Espanyol on November 3, and his manager Hansi Flick explained afterwards: “Ferran Torres wasn’t with us today — his mind was on the Valencia floods. When he said he didn’t feel ready to play, of course, it was OK. Some things are more important than football.”

On Saturday, at least 130,000 people protested outside Valencia’s town hall, with many residents walking into the centre from the areas most affected in the l’Horta Sud towns to show their anger at the official response to the disaster. “We feel abandoned,” was one of the banners flown by the protestors.

Within football, a crisis committee to support those affected by the DANA was announced last week by La Liga, the Spanish federation (RFEF), Liga F (women’s league) and the presidents of the Valencian and Castilla-La Mancha regional federations. Federacio de Futbol de la Comunitat Valenciana president Salva Gomar has estimated that at least €20million will be required by clubs in the region to rebuild.

“Through the crisis committee, I’ve requested financial assistance for a recovery plan to rebuild the destroyed stadiums,” Gomar told The Athletic. “Many professional clubs are ready to help with this. It will take a long time — cleaning up and rebuilding. The federation’s objective is to return optimism and joy to the kids, by getting them playing football again.”

Installations at more than 60 local clubs were flooded, affecting more than 1,000 different teams across all age-levels, and around 20,000 players. Among the clubs who have lost almost everything is Union Deportiva Balompie Alfafar.

“Our ground is completely ruined,” UDB Alfafar president Manuel Visiedo says. “It’s being used now as a dump for the rubbish collected from houses and streets. It’s all being crushed and baled to be taken away. The stadium… we’ll have to start again from scratch.”

UDP Alfafar have already started a crowdfunding campaign for their reconstruction project. Visiedo also says that more money from elite football should flow down to help the clubs which have been affected. “I understand the authorities currently have other priorities, but we’ve lost everything — all our trophies, all our footballs, everything,” he said.

Iborra says that professional teams in Spain and elsewhere should come together to offer financial and other support.

“Professional football can help a lot,” he says. “Social actions can raise money to repair many things. Many people are showing solidarity — in Valencia, Spain, all over the world. I’ve had calls from Greece, Turkey, to ask what they can do. Among us all, we can do it.”

Manises’ stadium is on higher ground and was not damaged by flooding. Their next game will be the rescheduled Copa tie against Getafe on November 26.

“People in our club have lost friends, work colleagues and former team-mates,” Marin says. “Others saw people being carried away by the water to their deaths. So nobody has wanted to think about football. Still, in the end, you need to return to your routine. Sport can be a positive way to decompress, to escape, clear your head. In the end, football can help people a lot.”

(Photos: Dermot Corrigan, Getty Images; design: Dan Goldfarb)