HOMESTEAD, Fla. — Just past noon on a humid Friday afternoon in South Florida, a grinning, bespectacled man wearing a purple polo shirt and black dress pants was standing in the way of a stock car being pushed through the NASCAR Xfinity Series garage at Homestead-Miami Speedway.

“Got my chance, Wayne!” a crew member on Josh Williams’ No. 11 team called out as he steered the slow-rolling car toward series director Wayne Auton, who smiled wider and sidestepped the vehicle before getting hit. “Love you. Mean it!”

On this day, Auton made his typical rounds in the Xfinity garage as the cars prepared for inspection. As he dipped in and out of garage bays, Auton stopped to crack a joke with one crewman, dished out hugs and watched teams make last-minute adjustments after unloading their vehicles.

Hardly anyone walked by Auton without comment as he greeted everyone from team owners to tire specialists on a first-name basis. It seemed like the Xfinity garage was his own personal episode of “Cheers.”

This has long been the routine for Auton, who has been traveling as a NASCAR official since 1987 — but only for another week. Auton will retire from the road life after next week’s season finale at Phoenix Raceway, capping a four-decade career in the garage — including the last 33 as a director for various NASCAR series.

Free, daily sports updates direct to your inbox.

Free, daily sports updates direct to your inbox.

Sign Up

“I don’t know if there’s ever been a series director that everybody is going to miss so much,” reigning Xfinity champion Cole Custer said. “He’s probably the most personable leader at NASCAR. Even when you disagree with him, you can always respect him just because of the guy he is.”

Auton is a throwback, one of the few remaining officials with roots predating NASCAR’s boom in the 1990s. He called himself a student of four well-regarded NASCAR executives: Bill France Jr., Les Richter, Mike Helton and Jim Hunter. Auton has blended their leadership legacies into a combination of principal, teacher, boss and dad.

“He’s like this fatherly figure to everyone,” said Brad Perez, who both races and works as a crew member in the series. “And honestly, this series needed someone like him. He’ll let you make moves, but if it’s a bad one, he’ll say, ‘Why? Why would you do that? That doesn’t reflect well on you or me.’”

France left an early impression on Auton with his ability to be visible and present with people while also maintaining order in the garage. Yes, NASCAR has to lay down the law; but doing so in an authoritarian way can quickly change the entire feel of a series. Instead of ordering Auton around and telling him what to do, France would often phrase it as a suggestion: “Have you ever thought about doing it this way?”

“He’d tell me, ‘If we don’t work with them, why would they even think about working with us?’” Auton said. “Our job is hard enough without having to be an S.O.B. to everyone.”

Of course, that’s not easy to do. By nature, the teams and drivers are not on the same page as NASCAR. In many cases, they’re trying to pull one over on Auton and his officials — that sort of “innovation” is how fast cars go fast, after all. Auton has had to dish out plenty of punishment, but he’s not offended when someone smiles at him one minute and is found to be cheating the next.

“If you take this job personally, you don’t need to be in here,” he said. “I tell our people all the time: ‘We are not their enemy. That approach is going to get us nowhere.’”

That attitude extends to the driving corps as well, and Auton takes particular pride in helping foster along many of NASCAR’s up-and-coming racers. As drivers in street clothes began to make their way into the garage and walk to their haulers, almost all had some level of interaction with Auton along the way.

A fist bump from Kyle Weatherman. A bro hug from Chandler Smith. A playful belly rub from Williams, plus an invitation for a post-retirement night at the short track.

“I hope you’re going to show up and hang out with us,” Williams said. “We’ll get a cooler full of beer. I’ll drop you off if you get too intoxicated.”

Auton spotted Jesse Love and girlfriend Georgia Kryssing walking toward the Richard Childress Racing haulers.

“You still hanging around with him?” Auton called out to Kryssing. “I thought you and me talked about that!”

There are more serious exchanges, too. Auton excused himself when he saw JR Motorsports driver Sammy Smith approaching, one week after Smith stopped on the track to bring out a caution at Las Vegas Motor Speedway before re-firing his car and driving away.

“Hi, Sammy. Tough week,” Auton said.

Smith wasn’t penalized at the time, but Auton made it known he wasn’t impressed by the sequence of events and got reassurance from Smith it won’t happen again.

Auton warmly greeted first-time Xfinity Series driver William Sawalich, but then asked if Sawalich took his advice and practiced an escape from his car on the passenger side before arriving at Homestead. When Sawalich said he didn’t, Auton responded with the tone of a disappointed parent.

“William Sawalich!” he said. “Wrong answer. Can you or can you not go out the right-side glass?”

Auton let Sawalich leave and told the 18-year-old NASCAR was happy to have him in the series but then shook his head. Auton has told every rookie in memory the same thing: to be familiar with how to locate the passenger side window in case the cockpit is filled with smoke and they’re pinned up against the wall on the driver’s side.

NASCAR Cup Series championship contender Christopher Bell even said Auton’s advice in that regard is so valuable, he’s adopted it in each vehicle for the rest of his career — most recently when the new Next Gen car arrived two years ago.

“Can you get to the bathroom in the middle of the night without walking into something?” Auton said. “You need to be that familiar with how to get out of your car.”

It’s something Bobby Labonte taught Auton decades ago, and safety is of paramount importance to Auton. People ask him all the time to identify which races over 30-plus seasons have been the best, and his answer is consistent.

“The best race is one where everyone goes home safe,” he said. “That’s a great race.”

Auton paused, then shifted his tone.

“It’s going to happen again, no matter how well we do our jobs,” he said, then repeated the sentence with emphasis on each word. “It’s. Going. To. Happen. Again.”

“It,” of course, is the death of a driver. Auton would know. In February 2001, he was the official designated to impound and secure the wrecked car of Dale Earnhardt Sr. — a man Auton had known for most of his life — after the driver’s fatal crash in the Daytona 500.

He doesn’t want to talk about what he saw inside the car, but he was shaken enough that it’s stuck with him. Auton made sure the public was kept away from the wreckage of the No. 3 — from the time it was loaded into a trailer at Daytona to the time it left a closely guarded building in Conover, N.C., following a NASCAR examination, headed toward a secret location.

Auton was also the person tasked with bringing Earnhardt’s friend Ken Schrader to the NASCAR hauler on that fateful day so officials could inform Schrader of the bad news.

That bond with drivers has been long evident and continues to this day. Cup Series driver Ross Chastain, who raced in both the Truck and Xfinity Series when Auton was series director, said he’s sought advice from Auton for years on a variety of topics.

And Noah Gragson, who had to be disciplined by Auton at times during his tenure in the Xfinity Series, called Auton “the best series director I’ve ever worked with in any series.”

“He’s light years away from the other guys,” Gragson added. “Not saying the other guys are bad; that’s just how good he is.”

Auton is known to have some tough-love conversations when necessary and can flip between cheerful and chiding. He gives more leeway to young drivers, but veterans “ought to know better,” he says. He’s not afraid to remind a competitor who crosses the line that “what you are doing is not making the sport any better.”

That said, the teaching moments don’t always go as planned.

In 2006, Brad Keselowski was a 22-year-old part-time Truck Series driver and had spent months repairing a damaged truck in preparation for a race at Homestead — only for Jack Sprague to wreck him in the season finale.

So an angry Keselowski plowed into Sprague on the cooldown lap after the race, figuring if he was going to have to fix his truck all offseason, then Sprague would, too.

A furious Auton called Keselowski to the hauler and asked what happened, and Keselowski tried to make an excuse. So Auton, ready to present some evidence, attempted to show the replay on an old TV/VCR combo — except it didn’t go as planned.

“It proceeded to eat the tape, and he’s got the play button running and the tape is just flying out of this thing,” Keselowski said. “It just made him even madder. Just smoke coming out of his ears. He just told me, ‘Get the hell out of here! Don’t ever do that again!’”

Other times, Auton has had to shoulder the blame on behalf of NASCAR.

At Richmond Raceway in Sept. 2013, RCR driver Brian Scott led the first 239 laps of a 250-lap Xfinity race and was en route to what would have been his first career victory. But Keselowski clearly jumped the final restart, which Auton immediately noticed from the tower and brought to the attention of senior officials — except Auton was overruled, and there was no black flag issued.

Keselowski won the race, and livid team owner Richard Childress arrived with Scott and RCR’s Eric Warren at the NASCAR hauler afterward.

When Auton shut the door to the office, he recalls, he told the trio: “Hold on. Let me talk first.”

“This better be good,” Childress said.

“Here’s the deal,” Auton said. “I’m not going to B.S. you, I’m just going to tell you straight up: We F’d up the call. Brian, you should have had your first win.”

Childress didn’t skip a beat. There was nothing he could say in response.

“All right boys, let’s go home,” Childress said.

Everyone shook hands and went their separate ways.

“We might not be able to go back and change it now, but we can own up to our mistakes,” Auton says now. “Somebody has to do this job, but how you do it is reflected by how they perceive you.”

With the races now dwindling, both drivers and crew members are having a hard time accepting the thought Auton won’t be around anymore.

You’ll still come and see us, they’ve told Auton.

Nope.

“When I walk out of Phoenix, that will be it,” Auton said. “And the reason is I have respect for the guys taking over. I don’t want to walk back into the garage and someone says, ‘Got a minute? I need to vent.’

“I’ve already told Eric (Peterson, the series official who oversees inspection and is taking over for Auton), ‘If you need to make a change from how I did things, then make a change. You’ve got to find your own niche, and I don’t want to do anything to interfere with that.’”

That said, Auton knows it won’t be easy. He can’t get himself to finish the sentence about what it will be like to walk out of the garage for the final time next weekend, but he suspects it might really hit him when the haulers leave for February’s Daytona race without him.

A life in racing will do that to a person. Auton’s father, Hoot, was a NASCAR official, which exposed him to the sport as a youth. At age 8, Auton recalled meeting NASCAR founder Bill France Sr. during a race weekend at Rockingham Speedway and telling him, “I’m going to work for you someday.”

That’s been the case for both Wayne and his brother, Buster — who will have been with NASCAR for 50 years next season.

Wayne’s own path started when he was chief steward at a dirt track in Hudson, N.C. He got the chance to travel as a NASCAR inspector with the now-defunct Dash Series, then moved up the ladder quickly to become series director. Midway through the Trucks’ inaugural season in 1995, Auton moved over to that series and held the position until 2013, helping the Trucks blossom with an identity of its own.

This week, we went behind the driver with Brad @Keselowski.

See how “uncle” Wayne Auton, former @NASCAR race director, impacted his life as he was coming through the ranks. pic.twitter.com/2GJEylpgo6

— NASCAR on NBC (@NASCARonNBC) October 13, 2019

Auton was fond of making his rounds at the various truck teams, checking in on crew members and taking them out to lunch — though a NASCAR official’s presence wasn’t always welcome by some.

One time, Auton stopped by the Dale Earnhardt Inc. shop and was invited inside by the team. While chatting with employees, he suddenly found himself placed in a rear chokehold by Earnhardt himself.

“What are you doing in my garage?” the gruff Earnhardt asked.

“You invited me in!” Auton replied. “I thought he was going to pop me like a pimple.”

At the end of 2012, Auton’s bosses came to him with the opportunity to run the Xfinity Series, but with an interesting mandate.

“We need you to change the culture,” they told him.

He’s reluctant to take any credit for being successful with that (“Wayne accomplished zero; we accomplished a lot,” he said of the series officials), but Auton immediately lights up when told of a commonly expressed fan sentiment: Xfinity is the best of the three NASCAR national series.

“It’s absolutely the best,” he said. “I tell everybody that. I get former Cup guys all the time who tell me they’ve come to work in this garage because of what we’ve got here.”

But it’s Auton who set the tone. On one hand, he’s so institutionalized into the “NASCAR Way” that he instinctively peels the label from a water bottle as soon as he takes it out of the refrigerator — even at home, when no one is watching. Wouldn’t want any inadvertent sponsor conflicts, after all.

On the other hand, every driver who has raced in one of Auton’s series has a shared experience: Phone calls on every birthday and major holiday.

“It’ll be my grandparents and Wayne Auton,” Harrison Burton said of his Christmas morning calls.

“You answer the phone and he’s singing a song to you,” Daniel Hemric said of Auton’s famous birthday messages. “It goes like this: ‘Fried chicken, country ham, it’s your birthday — hot damn!’”

To Auton’s two granddaughters, ages 9 and 14, he is “Pappy.” He picks them up at school at least once a week, and he wants to spend more time with them now that he’ll be off the road.

So Phoenix, then, will mark the end of that long journey. He’ll sign off from the radio as call sign 42 — chosen as the reverse of France Jr.’s 24 — after his traditional congratulatory radio message to the series champion following the checkered flag. Then he’ll raise a toast to the winning team after inspection has cleared in the garage before heading home.

Auton suspects it will be an emotional night.

“It’s going to be pretty tough walking out of there,” he said. “Even the times when the job sucks — it’s the people who made it fun.”

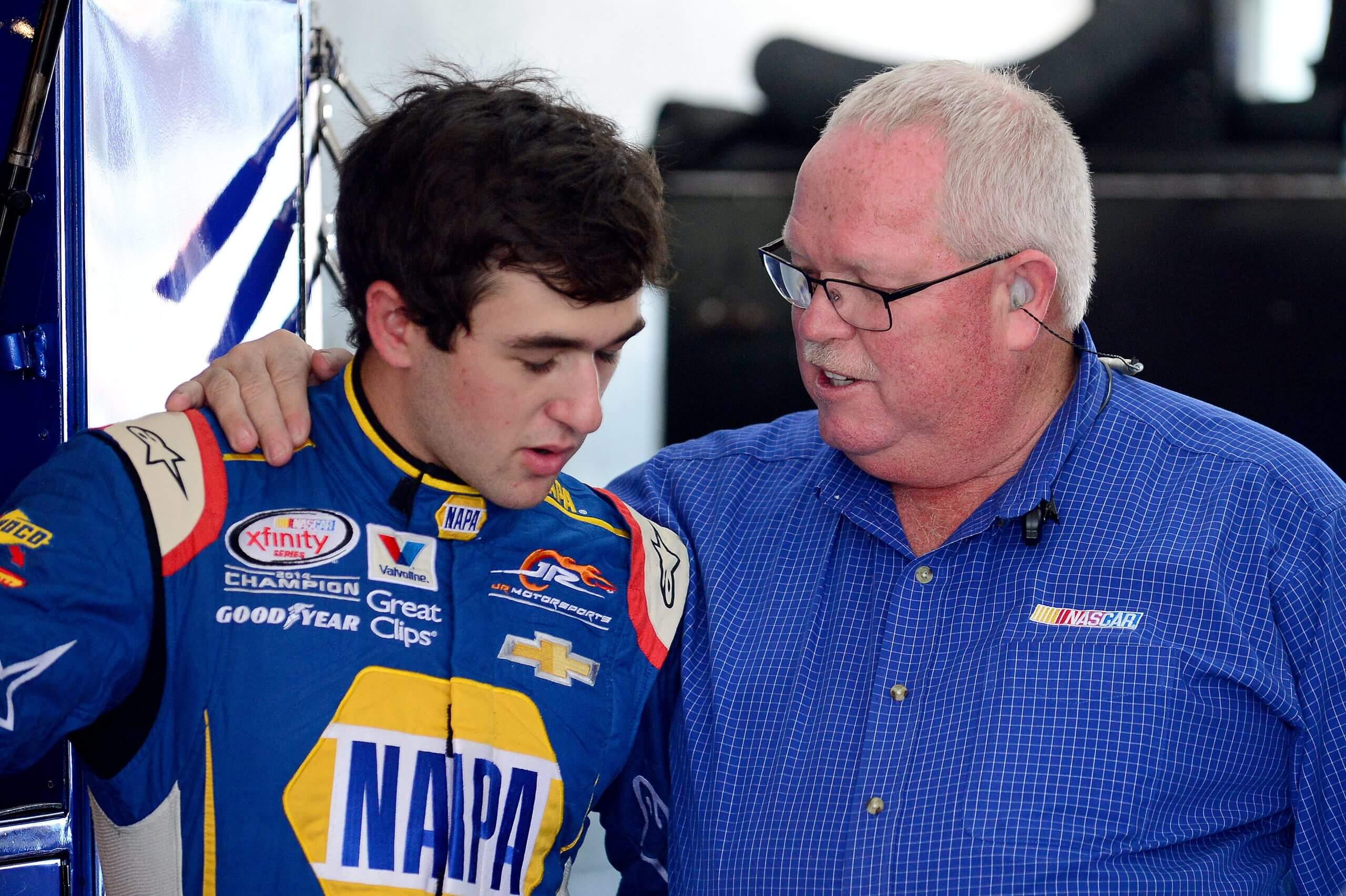

(Top photo of Wayne Auton in 2013, his first year as director of what was then called the Nationwide Series, now the Xfinity Series: Jonathan Ferrey / NASCAR via Getty Images)