Many rival fans have had a good laugh at Tottenham and their wildly fluctuating results this season.

On the surface, it makes little sense that the same team who lost to Ipswich at home could beat Manchester City 4-0 away, or the one that wiped the floor with Aston Villa could have fallen so meekly to Crystal Palace a week earlier.

This violent inconsistency is a problem for Tottenham, attributed to a variety of factors from Ange Postecoglou’s dogmatic style to a simple lack of common sense and basic individual errors from their players.

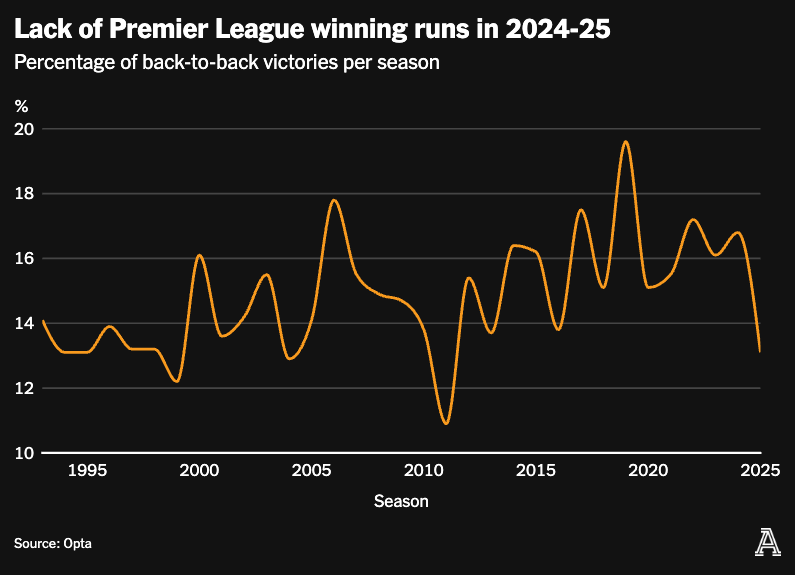

But this is not just a problem for Tottenham — it’s also a problem across the division. Inconsistency has been a theme of the Premier League season so far. In fact, it’s been the most inconsistent in a decade, since the 2015-16 season when Leicester won the league, and one of the most inconsistent in the history of the division.

It feels like nobody can string a run of wins together, and that feeling is borne out by the statistics.

After 15 games (14 for Liverpool and Everton), there have been 39 instances of teams winning back-to-back games. That’s compared to 47 at the same stage last season, 45 in the two seasons before that, 43 in the two seasons before that and in 2018-19, there had been 59.

Seven teams are yet to do this: West Ham, Crystal Palace, Everton, Ipswich, Southampton, Brentford and Manchester United. Another three — Leicester, Wolves and Tottenham — have only done so once. That’s half the division that, over a third of the way into the season, is yet to put together what you might call a ‘winning run’.

The longest winning streak currently in the Premier League is four games. Last season at this stage it was six, and looking back over the last decade, it was nine in 2016-17 and 13 in 2017-18.

It’s only the second time in the last 10 seasons that only one (or fewer) teams have won at least 10 of their first 15 PL games, the other being 2020-21 — the Covid season, when everyone was discombobulated — when nobody did it. The only team with double figures of wins this season is Liverpool, who have stood out as a model of relatively serene stability, while most of those beneath them have thrashed about like fish on the deck of a ship.

The clear caveat here is that 15 games is a relatively small sample size. But if you extrapolate it over a full season, there have only been three campaigns since the start of the Premier League in 1992 with a lower percentage of back-to-back wins. They were 2010-11 with 10.9 per cent, 1998-99 with 12.2 per cent and 2003-04 with 12.9 per cent.

Tottenham are the inconsistency poster boys, which is partly because people just enjoy mocking them, their earnest and despairing fans and their manager insisting “That’s just who we are, mate” after they make the same mistakes for the 20th time.

But their mood swings really have been extraordinary: it’s become a cliche to say you don’t know which Tottenham is going to show up for each game, broadly because you really don’t know. In this calendar year, they have played 33 games, winning 14 and losing… 14. Their most consistent run in that time was four defeats in a row at the back end of last season.

But also consider Newcastle, who went from beating Arsenal and outclassing Nottingham Forest to losing limply at home to beleaguered West Ham. Brighton, every shrewd observer’s dark horse tip for the top four, defeated Manchester City at the beginning of November but in subsequent weeks couldn’t beat Southampton or Leicester. Bournemouth lost at Leicester then beat Arsenal in their next game. Forest are fifth but have only won back-to-back games twice. Manchester United haven’t won back-to-back games. Manchester City’s inconsistency has been slightly different, more clearly delineated between before November and after it. Even Arsenal haven’t managed to win more than three games on the spin.

And then there’s Brentford, who are the surprising name on the list of those yet to win two games in a row. Their inconsistency is slightly more geography-based, having won seven of their eight home games but lost six of their seven on the road, collecting just one point when not in the Heathrow flightpath.

It increasingly feels like this season’s Premier League features a few undeniably good teams, a few undeniably bad teams, and then a sort of melange of sameness in the middle.

Is this is good or bad? That depends on your point of view, and possibly which team you support.

But it has led to the situation where the current top four — Liverpool, Chelsea, Arsenal, Manchester City — is familiar, but the next six teams were in the Championship as recently as 2022, 2019, 2016, 2022, 2021 and 2022. There are just two points between Forest in fifth and Fulham in 10th. By way of comparison, the gap between those two places in the table at the same stage last season was 10.

It is, most relatively neutral observers would probably agree, pretty entertaining to have the division so tightly packed like this, and probably a good thing that teams can get promoted from the Championship and become relevant, rather than going straight back down.

The question is why this is happening. The tightness in that middle part of the table suggests a lot of the teams are of a pretty similar level, which will inevitably lead to everyone taking points off each other. Of the teams in that sixth to 10th group, Villa have beaten Brentford who have beaten Bournemouth, Fulham have beaten Forest who have drawn with Brighton who have been beaten by Fulham who have been beaten by Villa. That cycle will probably continue until the end of the season.

Equally, the teams in that middle group have proven they have an upset in them: Forest beat Liverpool, Brighton beat City as did Bournemouth, who also beat Arsenal.

The classic old line everyone being able to beat everyone in the Premier League might have some truth in it. You could either view this as the standard of the top teams falling or those in the middle rising towards them, but it’s more likely to be the latter, broadly because of money.

English teams have been able to outspend all but the very biggest European clubs for some time now, but it felt like it rose to a new level this year.

Bournemouth, a club with a ground capacity of under 12,000 and whose highest ever finishing position is ninth in the English top flight, could afford to buy Porto’s centre-forward, Evanilson, for £40million ($50.8m) in the summer. Brighton spent around £200million, which included plucking choice talent from legacy European giants Celtic and Feyenoord. Forest seem to be muscling in on the ‘young Brazilian imports’ market, usually the preserve of the big Portuguese clubs.

But PSR rules have meant a sort of equalisation within the division too: everyone has a lot of money to spend, but they can’t necessarily spend significantly more of it than their counterparts. In this case, the rising tide may have raised all ships.

Simply on an aesthetic/anecdotal level, the standard of the Premier League feels much higher than it was, say, 10 years ago. There aren’t as many managers playing ostentatiously negative football: instead, you have Andoni Iraola, Fabian Hurzeler and Thomas Frank, in different ways, emphasising positivity. When the clubs in the middle of the table have progressive coaches like that, it’s obvious the standard is higher, and thus more teams have the ability to win more games.

And teams really are attacking more. There have been 449 goals scored in 39 games so far, which works out at a rate of 3.01 goals per game: this is continuing a theme, with last season’s rate of a touch over 3.2 the most we’ve seen in the English top flight since 1963-64 (3.4 per game). Prior to this last season and a half, there hadn’t been a goals-per-game ratio of three or more since 1966-67.

The goals aren’t entirely top-loaded either: Tottenham in 11th have scored more than Liverpool at the summit, and second-bottom Wolves have the same number of goals as sixth-placed Aston Villa. When goals are spread throughout the division, one consequence is that results fluctuate.

Many teams have instinctively attacking styles, and many are pretty dogmatic about those styles too. This inherently means more risks, which then means more mistakes. Again, Tottenham are the obvious culprit here, but also consider teams such as Brighton, Bournemouth and Aston Villa.

Injuries are another factor. Significant spells out for Martin Odegaard, Rodri (as well as almost all of Manchester City’s defenders) and Tottenham’s centre-backs have been the most high-profile absentees and have made games less predictable. But Brighton have lost 17 players to various injuries this season, Ipswich too, Villa have been without 15. If you don’t have a reliable pool of players to pick from, being consistent becomes much more difficult.

Related to this, perhaps slightly more intangibly, was an incredibly busy summer when the European Championship, the Copa America and the Olympics were all held, all of which featured a large number of Premier League players and potentially impacted their levels of fatigue, and thus their ability to deliver stable performances.

Managers recognise the issue. “In the previous two seasons, by and large, I’ve gone into the games knowing what we’re going to deliver and there is a feeling of excitement before the game,” Eddie Howe told the media after Newcastle’s recent 4-2 defeat to Brentford. “I think we’re in a period now where that certainty isn’t quite there, there is a vulnerability about us at the moment that we need to fix.”

Ange Postecoglou was asked about Tottenham’s issues by Sky Sports recently. “Some of it is where we are at as a club at the moment,” he said. “We’re still learning to deal with certain things. It’s just part of our growth. The results aside — because the results can disguise things — the reality is that our performances have been inconsistent which is the thing we need to address.”

You wonder what this will ultimately mean for the title race. We have got used to 90 points being a minimum for a team wanting to win the league, but even if Liverpool are technically ‘on track’ for 95, maybe the quicksand of inconsistency will suck them in too at some point.

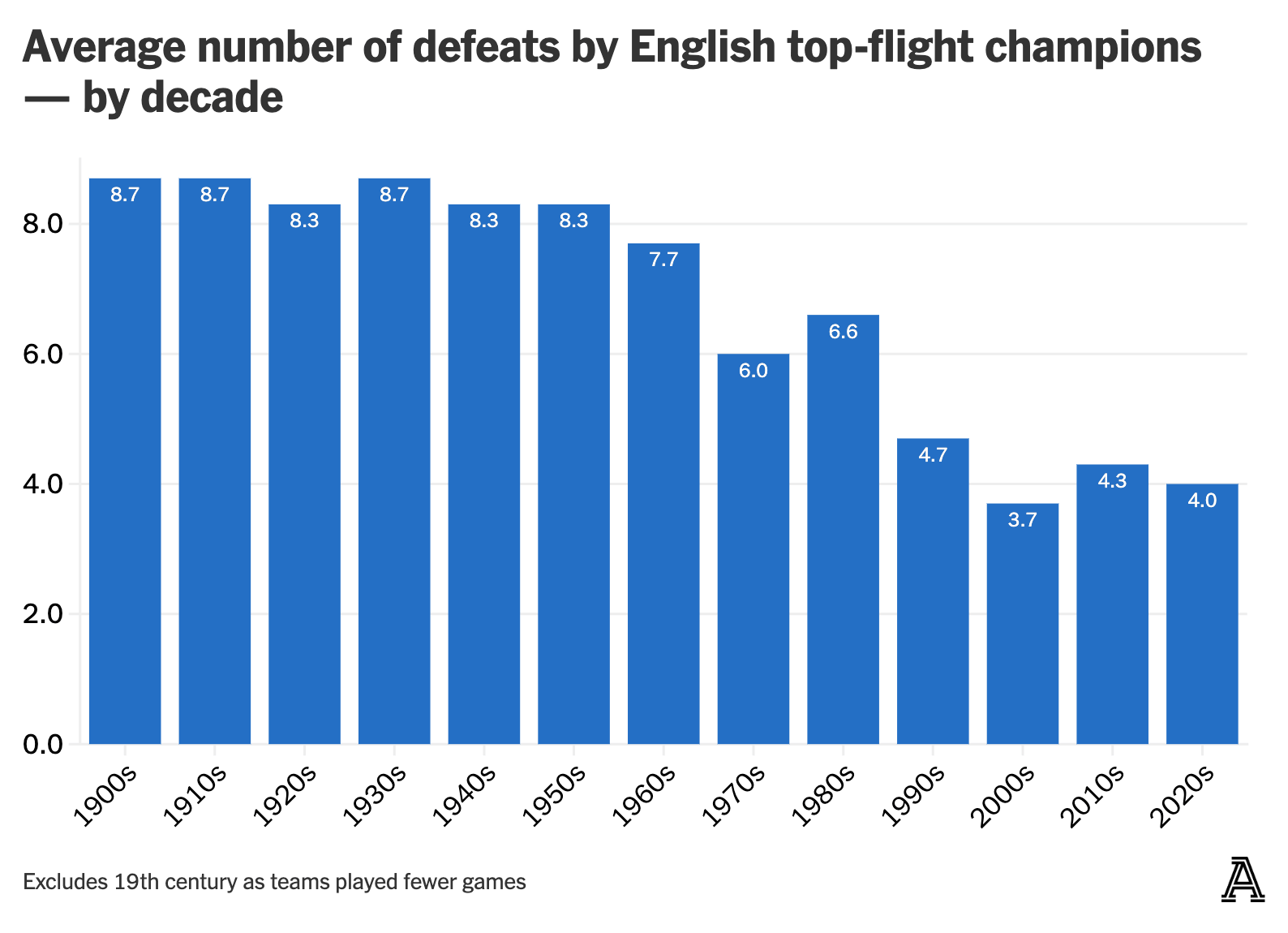

You can see from the graph above, how the number of defeats an English top-flight champion can afford every season has gradually declined to around four over the last few decades. City have already lost four, with Chelsea and Arsenal having two defeats apiece so they all have very little margin for error in the remaining 23 fixtures.

Perhaps this will be the season when that top line will drop, when the general lack of reliability in the division will mean the magic number is not quite so high.

But throughout the division, results have fluctuated. Teams have found it incredibly difficult to put a convincing run of form together. Which surely makes things much more interesting.

The Premier League this season is inconsistent, but that isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

(Top photo: Justin Setterfield/Getty Images)